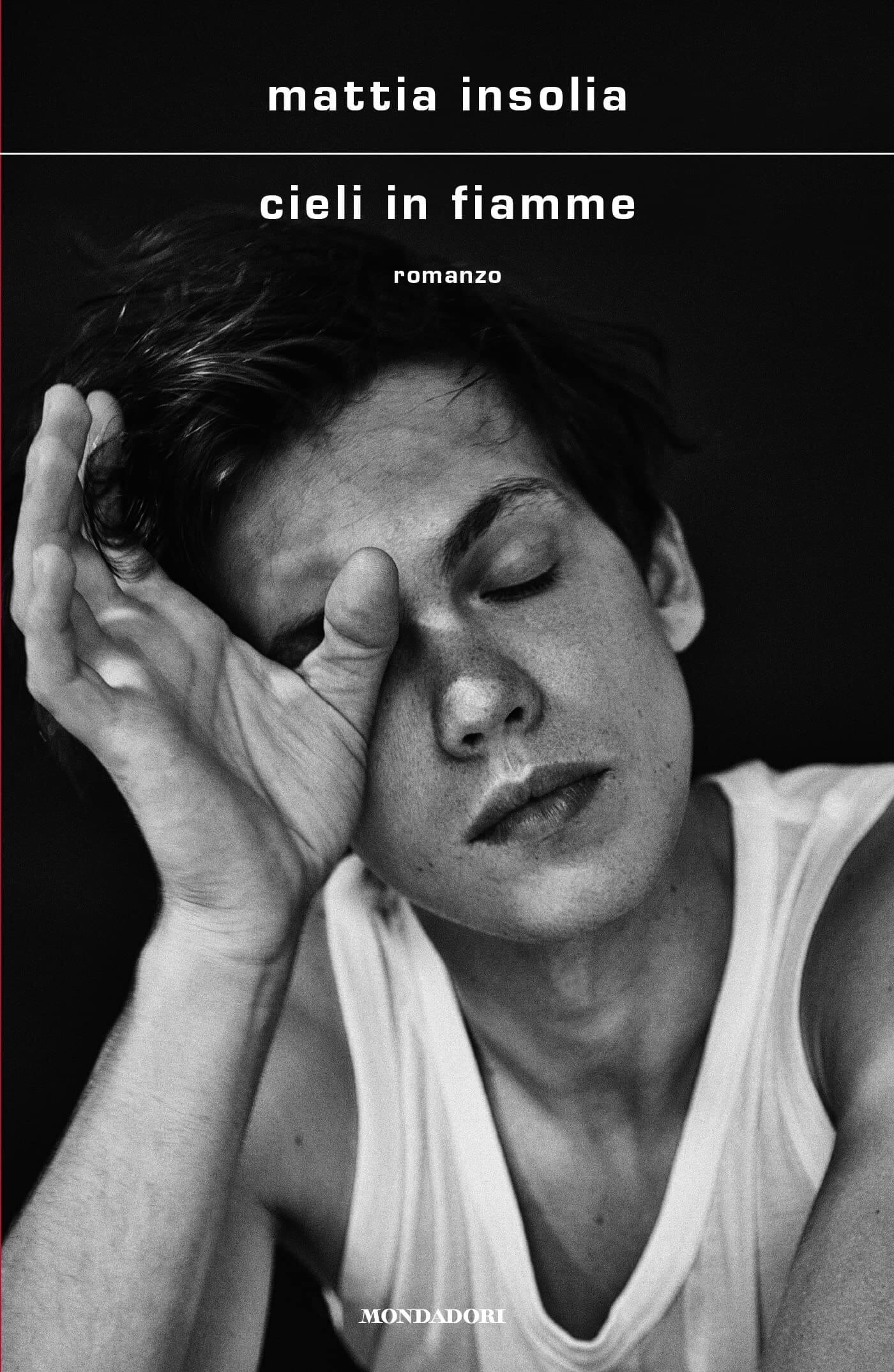

There are books that become something more, that increase the desire to go beyond that border, or rather, limit, between who we are and who we would like to be: there are conversations, born from these ideas, which further underline this desire, inherent in each of us, precisely because we are human. With “Burning Skies,” it was just like that.

With Mattia Insolia, the author, it was precisely this kind of chat: I sat down with him, and we let ourselves be carried away by the questions, but above all by his answers, to talk about characters who are inner creatures, the difference between pain and suffering, knowing how to be alone and the value of knowing how to be in community and seeking salvation in forgiveness. From the events described in his novel, which see Riccardo, Teresa and Niccolò confronting themselves and each other as a family, in the end Mattia mentioned that fragile, unpredictable and surprising experience that is life. Without ever forgetting that, letting ourselves “happen”, sometimes can do us good.

A first question that might seem obvious but where do Riccardo, Teresa, and Niccolò come from? Right from the start you have the feeling of knowing them forever, of having been on holiday in Camporotondo with them …

There is a very beautiful idea that Elena Ferrante wrote in her essay “In the margins“: for her, in every writer, there is a creature. Writers are just people who go around the world and make experiences, collect opportunities, meet new people, get hurt, suffer, and are happy … Then they take these experiences and bring them to the creature, which is within them. The creature is the one who decides what is right for it to become narrative material, and that must come out, either because inside it is crystallizing in a painful matter, or because it is a beautiful thing and therefore it is right that it comes out because it is a kind of source of happiness. Teresa, Riccardo, and Niccolò are experiences that I have had; they are emotional journeys, summers, they are like me when I was a kid, they are experiences that I brought to the creation without even realizing it and the creation put them together in the form of characters.

In this novel, the protagonists look at their parents and do not see points of reference, but people who are lost and with whom to clash rather than come together. This is a contradiction and form of confusion inherent to family dynamics that is very common and realistic, in my opinion. What would you like this description, this story, to leave to the readers?

I don’t think there can be a meeting without a confrontation. You only meet another person when you can see their point of view and recognize them as a human being. There are many people here, right now, but I am talking to you, I know your point of view on the novel and you are getting to know mine, but the point is that when we know each other in a really deep way, the clash is necessary so that we can create something that then becomes an encounter. There is a very nice series on Netflix called “The Beef“: there are these two very angry characters, and in this anger, they first clash and then realize that they have a common ground, that of anger, and they make it become material for communion, something on which to rest both.

I think that family dynamics work like this: I rarely saw my parents as points of reference in reality, it happened only when I grew up a little. I remember the first time I said: “Oh fuck, I see them as reference points”, and it was when I got my bachelor’s degree because I had a problem with the university and maybe I could no longer graduate in that session because of the bureaucratic stuff and the first thing I said was: “I’m calling my mother, Let’s see what he says.” And I had never done that, and she helped me. I never allowed them to be points of reference, and they never did my best to ensure that. In the novel, the umbilical cord is tight, and this leads to a tear, and I think that the two things can proceed in parallel: many families have an umbilical cord so tight that it becomes suffocating, others instead have it very long and therefore everyone has their freedom.

Suspended between what they would like to be, what they are, and what they have been concerning the context in which they grew up, Niccolò, Teresa, and Riccardo are looking for answers throughout their lives. Where is for you, both as a person and as a writer, the boundary between what we are and what we would like to be?

So, let’s start the psychoanalytic session (laughs). I don’t have an answer, but I don’t have it because the border is you. More than a border, it is a limit. Then said so it seems that we were all born the same and that there are no differences, that is, if we want to talk about something internal, I would like to be different: I, Mattia, would like to be less angry and less angry, I would like to be less sensitive about certain things, I would like to be less touchy. In this case, my limit is me, I have to do a job on myself, so that I can change. If, instead, we talk about “limit” from a more physical point of view, first of all, we must say that they are social limits, so a man has the road paved compared to women, a white woman has the road paved compared to a black woman, then we could talk about sexuality, etc.

But beyond this, the limit between what we are and what we would like to be is us. Riccardo, for example, would like to be many things, but he cannot because his limit is the past. This is something that scares me so much: the only real limit we have in my opinion is the past because we can no longer change it. We can prevent it from hurting us again or guiding our lives. There is a very beautiful phrase of Murakami, which says that pain we cannot avoid, suffering yes. We cannot go through existence without ever feeling pain, while suffering is something else. Riccardo, for example, has as his limit the pain he has created and that has become a sense of guilt. Teresa has his mother as a limit, Niccolò as a limit he has himself… So then everyone has their limits. I, for example, when think about my limits, my biggest is the lack of courage, in general.

Niccolò and Riccardo, in a sort of on the road that is more of a journey of formation, are in search of salvation, both for themselves and for their relationship. What does the concept of “salvation” represent for you?

When we seek salvation, we seek to escape from danger. So for me, salvation is a kind of inner state of tranquility. But above all, forgiveness. I am very capable of forgiving, but not of forgetting: in the sense, I forgive and then with that person I am fine, but I lose trust. And so perhaps there is also a little bit of salvation in that, that is, in forgiveness. For me, salvation is forgiveness. And, on the other hand, Riccardo makes that journey with his son to ask him for forgiveness for what he has done. Niccolò will ask for forgiveness from himself in the end probably.

“This is something that scares me so much: the only real limit we have in my opinion is the past because we can no longer change it. We can prevent it from hurting us again or guiding our lives. There is a very beautiful phrase of Murakami, which says that pain we cannot avoid, suffering yes. We cannot go through existence without ever feeling pain, while suffering is something else.”

The novel leaves us with the awareness that, while changing years and generations, the sense of loneliness, inadequacy, and insecurity, which in some cases lead to violence, are (unfortunately) always present. Growing up, how did you experience these feelings?

I was Teresa: at 16 I was like her, at her age I was short, and I grew up late. There’s this picture of me in high school, I took this picture next to the tallest classmate, I’m here and he’s here (laughs). Around the age of 17/18, I had very strong acne, and at that time I didn’t want to go out, I was ashamed, I didn’t even want to go to school, I didn’t want to go out, I didn’t want to do anything. But this led me to two things: on the one hand, to learn to be alone; Today I have no problem being alone, indeed, alone I am fine, but I can manage loneliness much more than being with people. Because being with people is something I learned later, and having learned it later, I learned it badly. And so on the one hand, that period educated me about solitude. Today I live it well, in that so-so period.

I still live the physical inadequacy badly: I feel ugly, I feel fat, and I feel everything I could be or not be; That is a very big source of stress for me, and it was even when I was a kid. Another thing, however, not going out during that period, I did all the experiences late: first kiss, first sexual experiences, first parties, everything late. And so actually, Teresa is me. That inadequacy, that shame of the body, I lived badly, the loneliness I lived better. I was talking about it with a very good writer, called Lorena Spampinato, I interviewed her and I asked her: “Were you shy as a girl?” And she replied: “I thought so, the others when I talk about it today, tell me that I was not shy at all”. So then the look we have on ourselves, deeply distorts what we are, both inside and outside. So I’m much cooler, that’s the conclusion (laughs).

How do you interpret the anger and fear of the generation of young adults of which you are, indeed, apart?

In my opinion, there is despondency and frustration. Our generation, in this case, has found itself in the corner from many points of view: we hear the word crisis from 2008 onwards every day, in economic, political, and environmental, work … The environmental one, for example, we are taking it and we will take it in the face: we are seeing it in Emilia Romagna, and later we will see it in a much stronger way. All these crises give us the feeling that we, a future, do not have it, not because something happened in itself, but because previous generations did a little what they wanted. They got rich. And we now find ourselves having to navigate in a pond, we are a bit like stray dogs fighting over bones, so in my opinion, the anger is that.

There is a very important difference between our anger, that of the millennials, and Generation Z: because we millennials have experienced this anger in a very individual way, but we have never done anything. We know what the crisis is, but we have never taken to the streets, and we have never cohesive around a single point. Generation Z has a little more of this, with Fridays for Future, for example, it has a greater capacity to make a community. We feel very “snubbed” in some ways, very sidelined: it is as if we are always trying to scream, to say that we have a problem, but no one listens to us. Then, there is also to say that each of us has his anger, which comes from something, but in my opinion first of all it is that.

“To be who we want”, Elena says to Teresa, is it possible? Or is it a form of utopia?

It is possible, but you must be ready to do battles. Society, ourselves, and the people next to us require us to be in a certain way, they require us to wear clothes, they force us to do things, to be things, and to behave in a certain way. It is possible to be whoever we want, but we must be ready for loneliness and quarrels. In my opinion, it becomes impossible because then it is inherent in man the desire to be inherent in society, to participate in a vision of the world. “Into the wild” in the end is this no? I want to stay out of it because the world has betrayed me, and above all because I want to be as I feel I am. It is difficult, but it is possible.

How do you “let yourself happen”, as Riccardo would say?

Me? Never. The question in the novel is why I asked myself when I was writing the book: I couldn’t find a center of gravity, I couldn’t understand what was missing. At that time, it was the end of the first year of the pandemic, I suffered a little from the hut syndrome; I didn’t want to leave the house anymore, and then at a certain point, I said to myself: “You’re always at home, you’re not with others, you’re not writing, what are you doing? Do you let it happen?” The answer was no, immediately. Because I’m a very anxious person, I’m an incredible hypochondriac, I calculate everything, I break the so-called poor people who work with me, and therefore I rarely let myself happen. I let myself happen in love, that is, when I felt a strong feeling for another person, in that case, I followed that feeling. Because in the end, it is this, letting yourself happen and not caring about the consequence, but obeying an instinct, following a desire. When I followed a desire that led me to another person, there I let myself happen.

What would you like to say to Riccardo, Niccolò, and Teresa if you could?

To Teresa, I would say that I am sorry because, in the end, she turned into what she did not want to become. She is not a true copy of the mother, but she is a very rigid person, who does not listen to her son, so she has followed a little bit in the footsteps of that beastly mother she had. To Riccardo I would say: “There is no need for you to kill yourself, there is a need for you to ask forgiveness, to pay for what you have done”. To Niccolò I would say “Do not disunite“, which is what Paolo Sorrentino said. Because the impression, in the end, is that he can take a solid form as happened to his father, but he has not yet become an adult, he has chances, but he must try to let himself happen.

What book are you currently reading?

“Young Mungo.” It’s beautiful, and it was also what I needed right now.

What untold story would you like to write next?

It’s not the one he’s going to write next, but, you know, I want to write a novel about an older person. Maybe because I feel old (laughs).

What’s the last thing you discovered about yourself?

I know how to cushion bad things better than I thought. I am a very sensitive person, very scared and worried about everything, from everything, for everything, with everything, about everything. But when I get something bad, I realized that I hold it up well. I think I called the bad luck upon me (laughs).

What is your happy place?

My friends. And my cats. And my parents too.

Thanks to Mondadori.