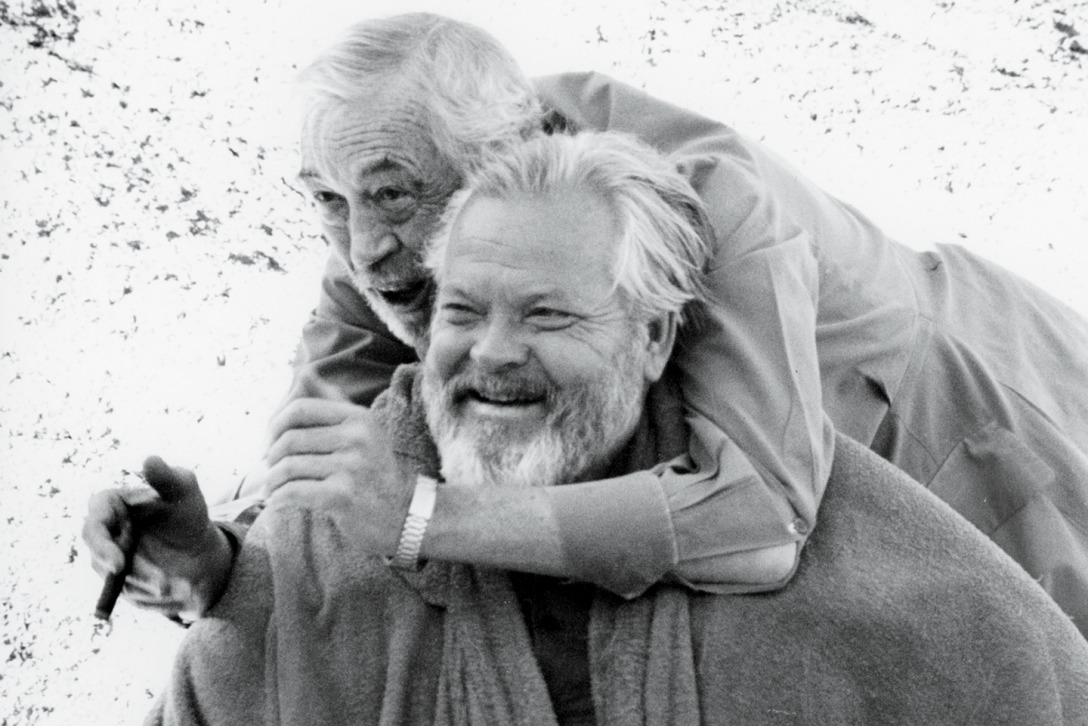

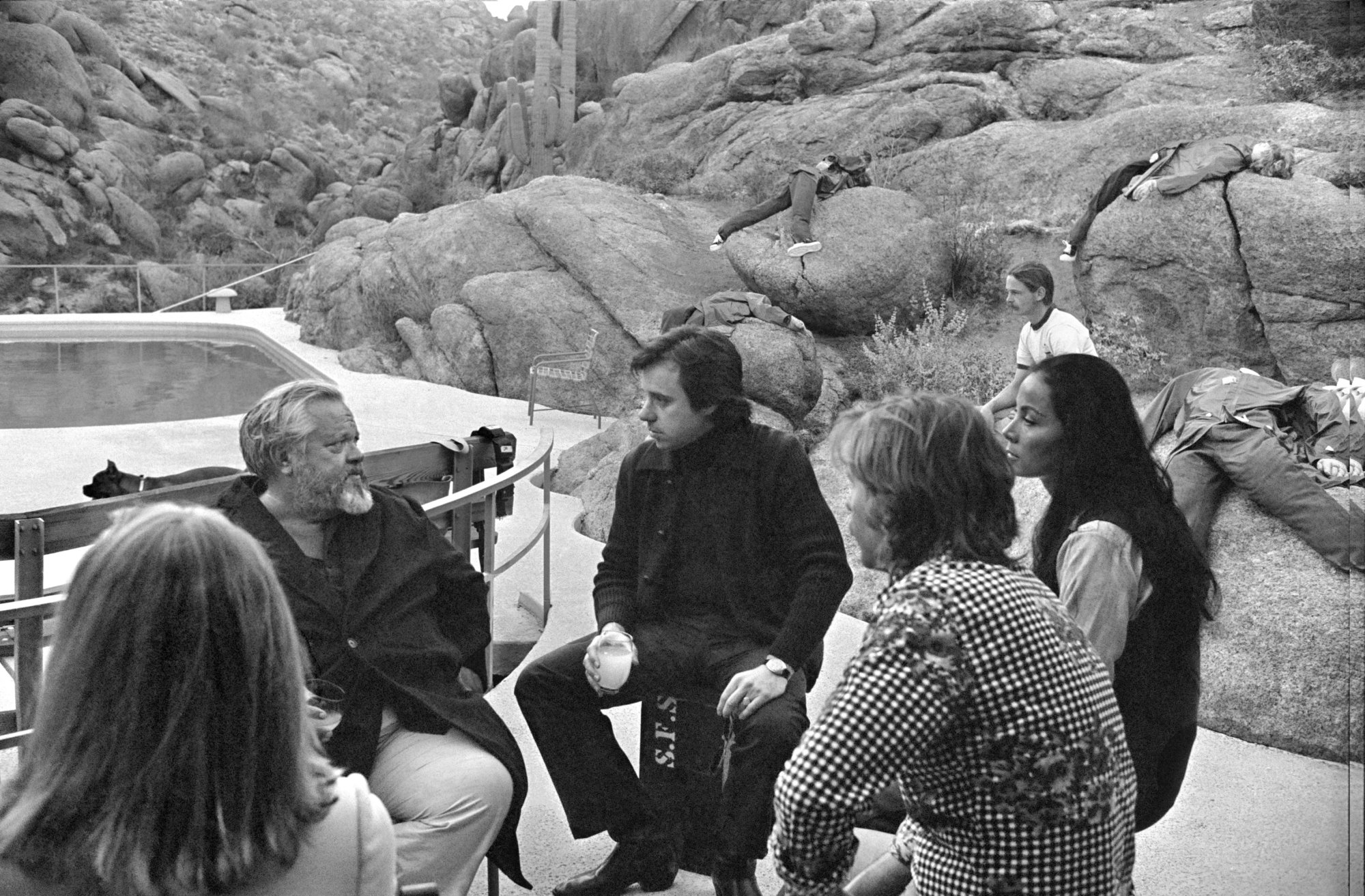

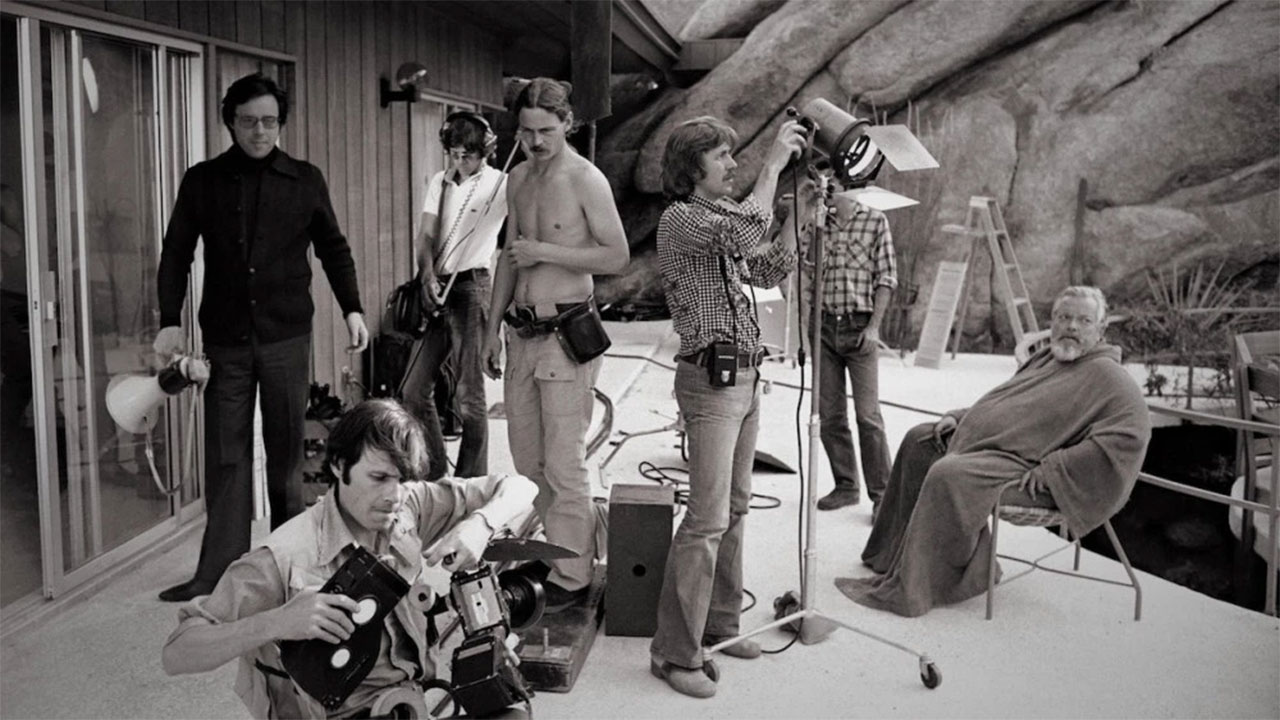

The 75th Venice Film Festival has been important for many reasons, but one of the main ones was the return of Orson Welles with “The Other Side of the Wind”!

While he was alive, the great director had a difficult relationship with the Venice Film Festival, after his “Othello” was destroyed by the critic, but he is acclaimed now as one of the greatest figures of all times in the very same rooms where he had been pointed out as overrated.

Also, a documentary has been created about the restoration of the movie, with the important title “They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead,” presented at Venice as well and available on Netflix from the 2nd of November.

In the crew, we find Daniel Wohl, composer and sound designer, who has told us about his world and how the sound universe is evolving, and how does it feel to relate with great names of cinema.

_____________________

The movie shows the last work of Orson Welles. Has your work for this film been influenced by Michel Legrand’s score, the composer who signed the music in “The Other Side if the Wind,” 3 times Academy Award-winner and Parisian like you?

_____________________

I’m a fan of Michel Legrand’s work, and especially what he made for “F Is For Fake.” I avoided any direct references to his scores for Welles’ films, but perhaps there are some unintentional commonalities inspired by the images of Welles’ films. I found that Morgan had very interesting and specific ideas about music. He approaches music with a deep understanding and refined sensibility.

One important influence on the score is early electronic music, particularly the musique concrète of Pierre Schaeffer which uses tape samples of every day, found sounds in musical ways. Analog synthesizers feature prominently in the score as well. The last factor and a source of inspiration for much of my music was finding a way to complement and mix those electronic sounds with acoustic instruments: specifically woodwinds and orchestral strings. All of these different source materials resulted in a score that is quite eclectic actually.

Specific musical elements and specific instruments are used to represent the various aspects of Orson’s own eclectic character. His humor and playfulness, come across in the low winds such as bassoon and bass clarinet, the wildness of his working process appear as swells of rapid synthesizer arpeggios. We also occasionally embrace a gritty or grainy production style to evoke Welles’ pre-digital era.

The musical style, mix and approach is very specific to each cue and varies greatly throughout the whole film.

_____________________

Which composers inspire you the most?

_____________________

There are so many composers who have inspired me. I studied with David Lang, and have worked with him recently on a scoring project. His music is both disciplined and incredibly intuitive. It’s very easy to listen to but is increasingly interesting the more you listen to it. It’s conceptual but not pretentious which is an extraordinary achievement.

Debussy was my first musical love. I went to school in St Germain en Laye, his birthplace, so I discovered his piano pieces fairly early on, which influenced me to become a composer.

Composers like Ligeti, Penderecki, and Xenakis or Reich, Riley and Glass have also been influential on me. And of course, electronic music, which was prevalent when I was growing up in Paris, was a huge influence for me. When I’m working on a project I’m always approaching it from a mindset of both a classical composer and an electronic music producer.

_____________________

Without any doubt, Welles was a genius in everything he did. He’s been one of the most avant-gardist and important directors of all time. In your opinion, who has taken his baton? And, as for the music, who are the geniuses of the past and now?

_____________________

Some of my favorite directors are Italian actually: Paolo Sorrentino and Luca Guadagnino are two of my favorites, but I can’t claim that they have taken the baton of someone like Orson Welles because it’s such a different style and lineage. Some trademarks of Welles are his use of nonlinear narrative and unusual camera angles or effects. I love those elements in the work of Michel Gondry, perhaps he has taken up the baton of some Welles’ avant-garde aesthetics.

Past and present musical geniuses whose work I keep coming back to include Messiaen, Johann Johannsen, Oneohtrix Point Never, to name a few. All of these are composers who use color and timbre in very different and innovative ways, which is something I prioritize in my own music.

“Color and timbre used in very different and innovative ways,

which is something I prioritize in my own music.”

_____________________

You have an interesting style, that matches the acoustic tradition with the electronic one. Do you think that the future of music will be monopolized by the electric sound design or that there will always be a space for the orchestral scores?

_____________________

I think certain sounds are timeless, like piano or strings. These sounds are so special because they are complex, rich and produced acoustically. There is so much detail in the hair of the bow on a string or the felt of a hammer striking a string in the case of the piano. Even though those components aren’t the loudest part of the overall sound, they make a huge difference in how we perceive them.

Also, the psychology inherent in acoustic sounds is something that always surprises me – our cultural associations with a bassoon or oboe are completely different from our associations with a synthesizer. I do not think acoustic instruments will be replaced any time soon as they serve very different emotional roles from electronic sounds.

“There is so much detail in the hair of the bow on a string or the felt of a hammer striking a string in the case of the piano.”

_____________________

What’s your take on the future of sound design?

_____________________

I often think that sound design and music are merging into one and the same. I feel that even some of my own pieces could almost be heard as folly. The future of sound design is probably sound that is hyper-real, a sound that is intricate, palpable and spatialized beyond the abilities of stereo or 5.1 systems. Many people are working on sound in virtual reality so that when you explore a virtual space and the sound moves based on your location.

Spatialized audio has a long history in experimental and academic electronic music, Varése’s tape piece Poème électronique was played on a system with over 300 hundred speakers in 1958 and there are plenty of composers still working in this tradition. But I think these ideas and techniques will play a bigger role in more mainstream sound design in the future.

_____________________

Orson Welles had a difficult relationship with the Venice Film Festival, with the downright flop of his “Othello,” and the title of your documentary makes even more sense with the premiere right here in Venice. During the last years, you have also worked in the production of “Mother!” by Aronofsky, that has been burned by the critic in Venice (by the way we wrote about how much we loved it). Why do you think that happened? And do you think that it will be revalued in the future?

_____________________

“Mother!” was an interesting project. I worked on it for a bit with the late great Johann Johannsson. He would send me certain cues he was working on to add layers or texture etc.

Halfway through the process, Johann convinced Aronofsky to not have any score at all in order to better serve the film. I can say though that the music Johann was working on was wonderful but it seemed that what the film demanded was a total absence of music and just sound design. I thought that the decision was a powerful one and that the silence was actually the best compliment to drama in the film.

_____________________

What can you tell us about the new TV series “Project Blue Book”?

_____________________

It’s based on an interesting backstory about a doctor, Allen Hynek, who was hired by the government to verify UFO sightings as a part of an Air Force program called Project Sign established in 1948. His job was to study UFO reports and judge their legitimacy. For the first few years, Hynek thought that most of the reports were just misidentifications of common things like planes or shooting stars. But Hynek’s opinions about UFOs began to shift over several decades, deciding that some reports actually showed genuine evidence of foreign objects.

Hynek had an interesting history himself with films. He was on set with Spielberg for “Encounter of the Third Type” – and Spielberg partly based his idea for the film on Hynek’s research. Bob Zemeckis, the executive producer for Project Blue Book, was a Spielberg protégé and of course, wrote “Contact” which is a film I’ve always loved.

So the history and lineage are interesting and it’s exciting to be a part of that world.

_____________________

Like you said before, the TV show will have Robert Zemeckis as executive producer, who has worked with some of the greatest names in the scores field. How was working with an institution such as him?

_____________________

It’s an honor to be working on a project that Bob Zemeckis is producing. His films were a part of my childhood so it’s been somewhat surreal to be working on the other side now. He’s been very supportive of the work we’ve been doing for Project Blue Book.

The score for this show is an interesting mix of horror and sci-fi. There are lots of dissonant string cluster chords, scratching effects, and other unusual string techniques with additional editing and effects processing on top of that. I’m really happy with how it turned out and looking forward to the release!