Ah, the roaring 20s of the 1900s, the years that, unlike the current ‘20s, were enlightened by glittering events, eccentric personalities, and new occasions. After the hard years of the war, people could finally feel, again and in a new way, the desire for freedom and for exaggeration, animated by a great will to rebuild and for rebirth, as simple as that.

These are the years pictured by Francis Scott Fitzgerald‘s books in America, while in Europe, writers such as Ernest Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, James Joyce, and Ezra Pound gathered at the Shakespeare & Co in Paris, run by Sylvia Beach, to discuss their (future) literary masterpieces.

It was a period characterized by the desire to leave behind the years of WWI to express yourself in new and original ways. This desire was also emphasized by clothes, which became rich in bright, “naughty” and libertine details. People left behind the simple and practical clothes to live their desire for emancipation with provocative solutions and exaggerated makeup.

And who dictated the style in those years? Whether it was in America or Europe and especially in England, we are talking about “scandalous” personalities, lovers of parties, and everything that went beyond the social conventions of the time. The real protagonists of fashion in those years were the Bright Young Things and the “members” of the “Gatsby Generation,” with all their desire to express creativity and exaggeration.

How? Having one limit: there are no limits.

THE HISTORY OF BRIGHT YOUNG THINGS

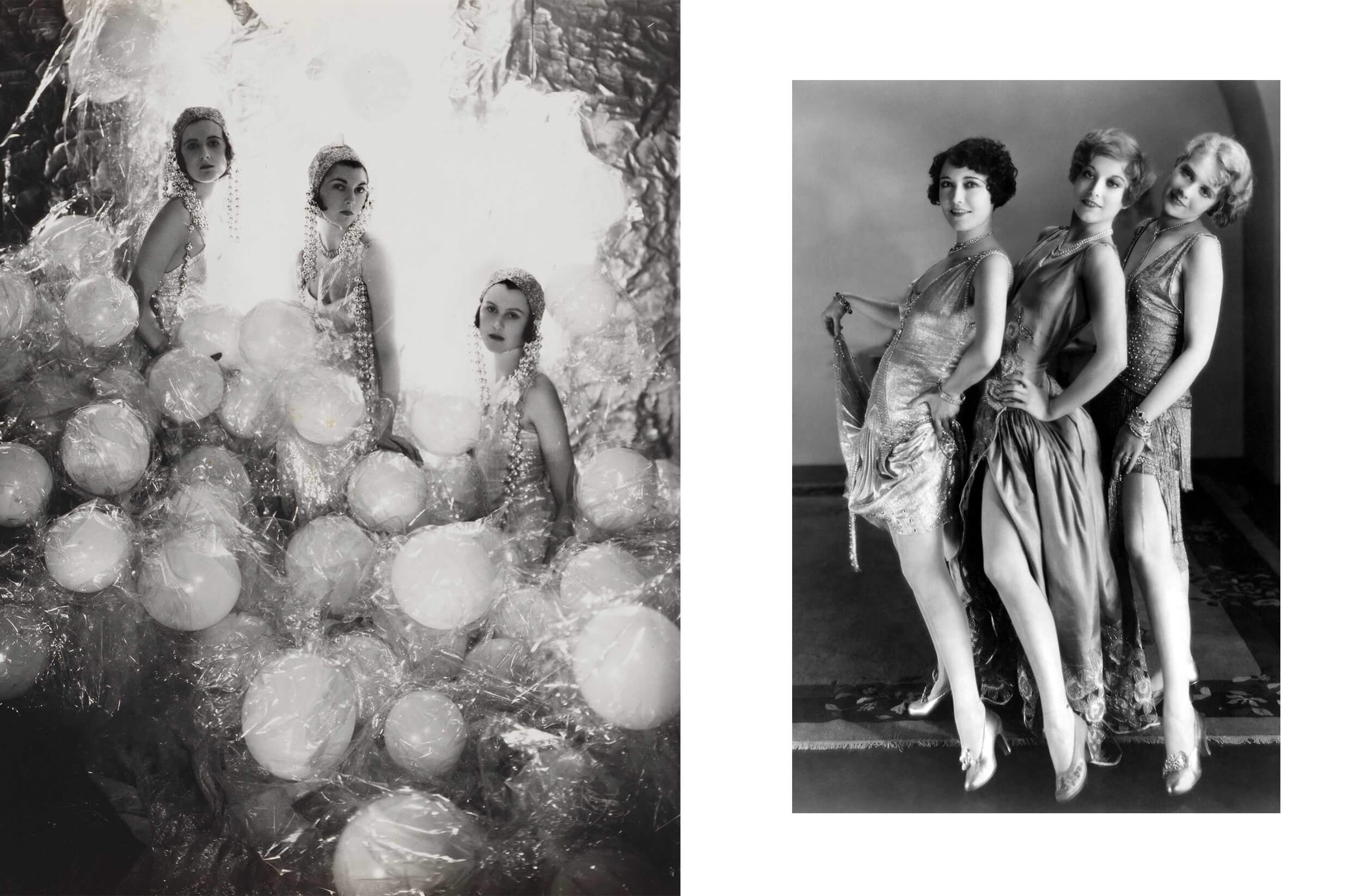

In the ‘20s, the British tabloids were all about them, the Bright Young Things (or Bright Young People), the rich heirs of aristocratic families considered outrageous for their exaggerated lifestyle, where masked parties, elaborate clothing, alcohol, and drugs were a must. A sort of bohemian group that invaded the streets of London, a kind of “celebrities,” as we would call them nowadays, who wanted to seize the moment and fulfill their desires after the hard years of suppression and crisis.

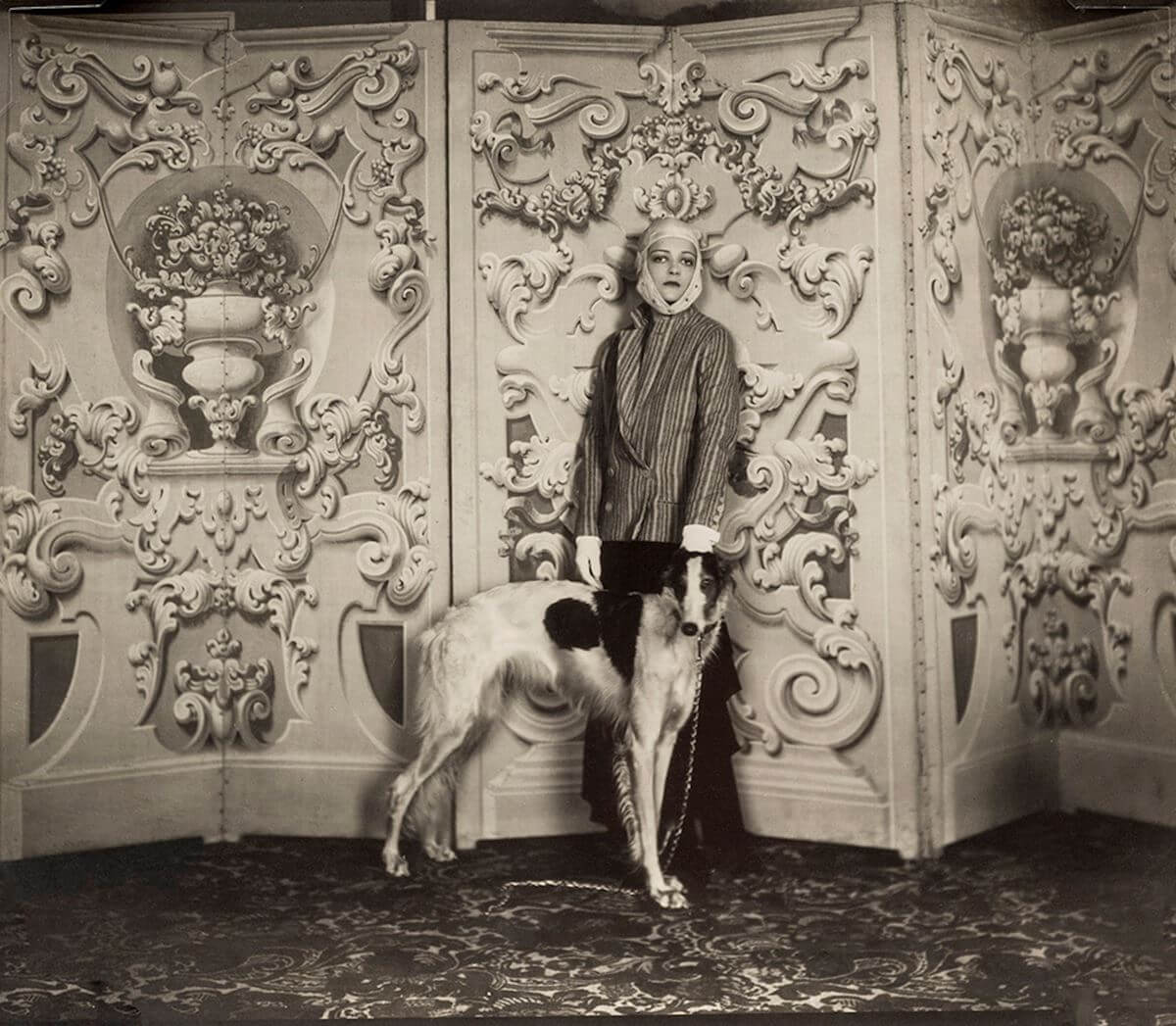

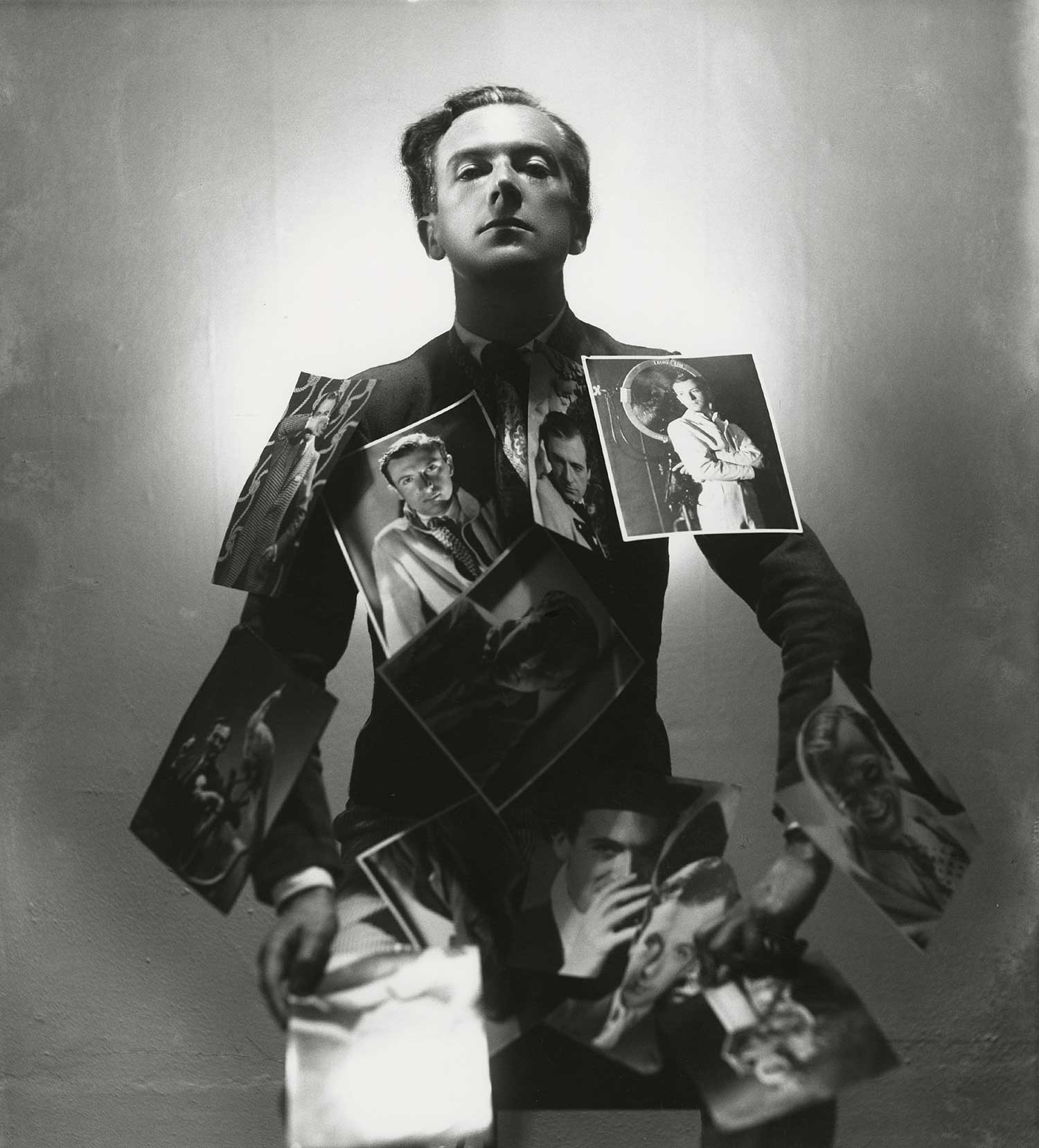

They were young women and men who were allowed everything, from treasure hunts on London public transport to trips in the countryside with the fanciest cars, up to the parties in their luxurious family estates. That’s where the myth of the Bright Young Things was born, captured by the legendary photographer Cecil Beaton who, in this context, took his first steps. Later, he would move on and win the Academy Award for Best Costume Design for “Gigi” and “My Fair Lady,” he would be a collaborator of Vogue, and become a famous photographer of celebrities and the British Royal family).

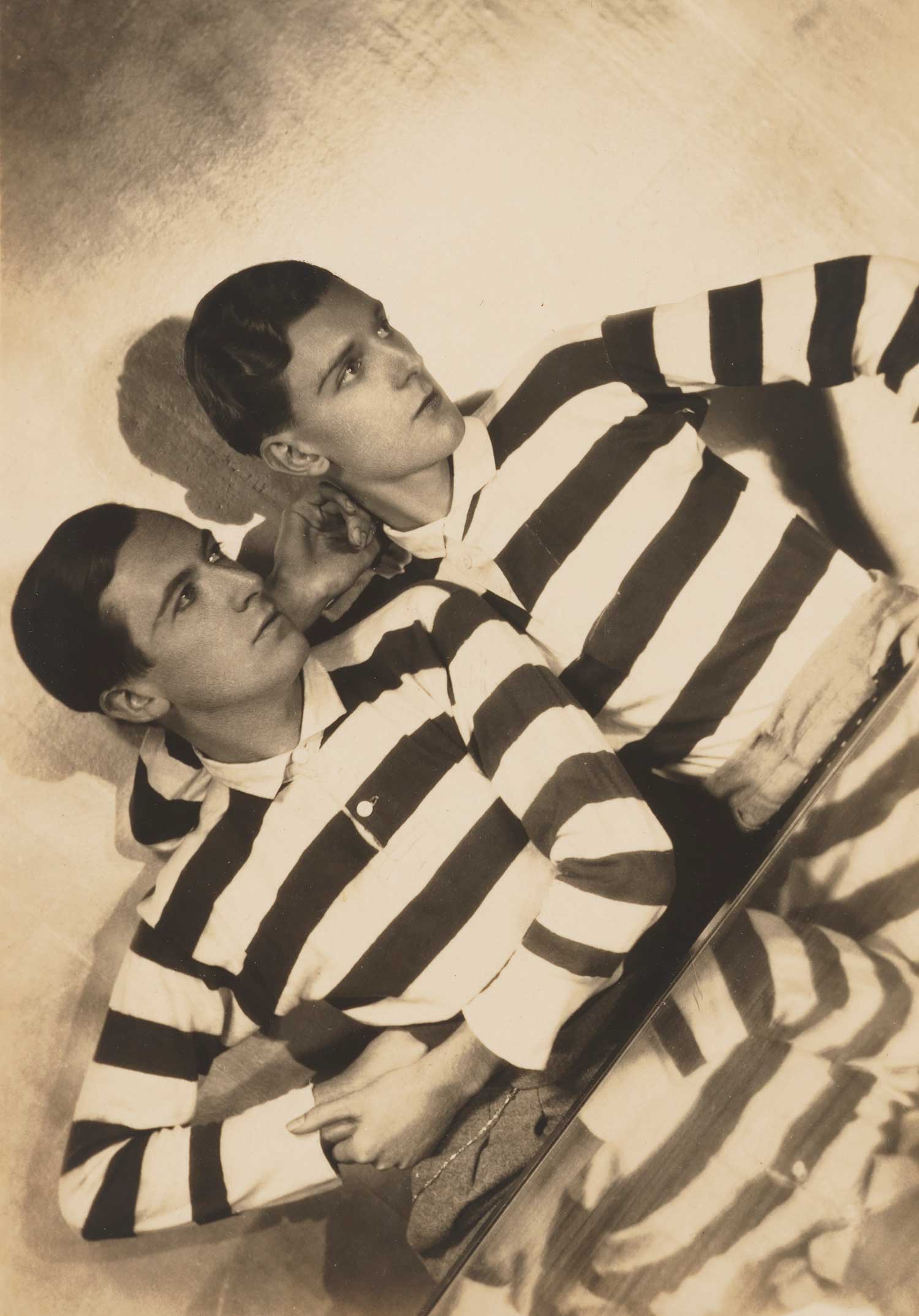

The parties were often themed, and jazz was the main soundtrack: here, you could breathe a wild atmosphere with acrobats, theatrical clothes, and narcotics. Women and men wore their flashy clothes, outrageous makeup (homosexuality was a crime in England in those days, but the group allowed their members to be whoever they wanted and to love whoever they wanted) and let themselves go to the absolute frenzy.

It was a sparkling decade and, just like a spark, it expired fast: in the 1930s, when unemployment was a huge problem, the Bright Young Things lifestyle was considered out of place and it was widely criticized, marking the end of a unique period in history.

BRIGHT YOUNG THINGS’ STYLE

Respecting the theme while being who you want to be, this is how you could define the style of this aristocratic group. Once the theme of the party was defined, its members were free to play who they preferred, in a combination of androgenic, feminine, and genderless style never seen before. Boys and girls, therefore, wore dresses and suits with bright details, flashy headdresses, and unusual accessories. They loved the gold and silver shades, the dots and the stripes, the decadent style and costumes, even in a satirical key.

That’s how Beaton immortalized them, and this is how we remember them: like the young generation who “brighten up” the fashion of the time in England, showing that the most effective look is the one that allows a person to express oneself freely and creatively.

THE HISTORY OF THE GATSBY GENERATION

In the 1920s, there was a will of starting again all over the world; Art Deco exploded in all fields, and Europe was looking curiously overseas, towards America, the land of cinema, jazz, charleston, and fox-trot, of cities that reached the sky with their skyscrapers, and where the desire to escape seemed particularly strong and shared by many.

These are the years captured by the pages of “The Great Gatsby,” those of a transgressive and optimistic youth who wants to have fun, dance, and rebel. A strong desire for emancipation (political, feminine, and social) resonated along the streets, and the night took the lead role: people went to clubs, to live music events, they would organize private parties, smoke, drink, and experience sexual freedom. In other words, they went back to life, and they started to experience a whole new life.

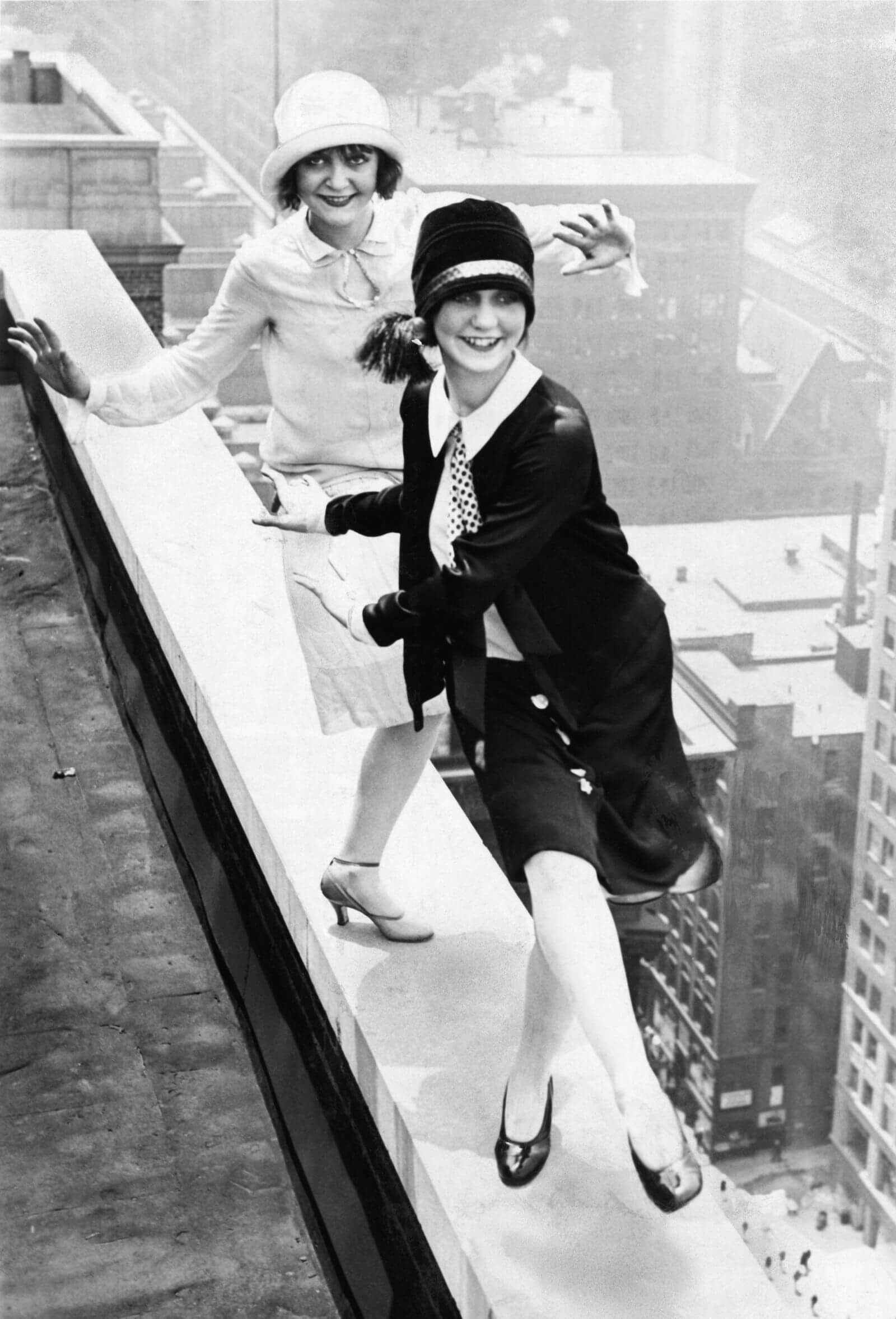

This change in lifestyle, which rediscovers well-being, was also reflected in clothing, especially female ones. Women become uninhibited, bold, and independent; they would drive, study, play tennis and golf, drink cocktails, and express their ideas. This attitude led them to give up to simplicity and to shorten the hem, to dress comfortably, and to feel a desire for provocative and innovative exhibitionism.

In this context of freedom and experimentation, the style of the “Gatsby Generation,” of Zelda Fitzgerald, the wife of the famous writer, flappers, and divas such as Joan Crawford, Norma Shearer, and Louise Brooks, was born.

THE GATSBY GENERATION’ STYLE

The girls of the time gave up on the practical and austere looks of the war period and began to discover new shapes that shared the concepts of autonomy, femininity, and comfort. The clothes, designed to move freely both during the day and during the wild night dances, had straight lines, with a low waist, and they were short, just like the haircuts.

Soft and light fabrics (chiffon, tulle, silk) and precious details, with fringes and beads, were a must, without the fear to show the legs. Feathers, stoles, very long threads of pearls, and sequins completed the look, without forgetting the cloche and the fur. Girls also liked intense colors such as burgundy and purple, and low-heeled shoes. Even men discovered extra comfort: the shoulders of the jackets became wider, as well as the trousers, and the two-pieces suits became a trend.

In this context, the flappers, a name that, in American slang, recalls the flappers of a bird’s wings, used to refer to the young casual women who did not fear other people’s judgments, were under the spotlight of social events and fashion of the time. With wide décolleté (never before had women exposed so much skin, also leaving neck and arms uncovered), fishnet stockings, short hair (the “bob cut” was their reference cut), and bold makeup, the flappers brought a breath of fresh air to the American streets. Their light, sometimes male, and tight looks, easy to sew and replicate, were accessible to members of every social class.

Women of this generation were the first “party girls” who danced scandalously, who wanted to escape prohibition and be under the spotlight, thanks also to the bold makeup that was all about lipstick and eye makeup with abundant khol. They are the exponents of a phase of passage to which it was impossible to resist, and whose roaring soul is admired and remembered even today in fashion and history.