Beauty. Beautifulness. Personality. Uniqueness. Acceptance. Expression. Art. A tangle of words that unfolds to the rhythm of mental associations, those that arise spontaneously when brainstorming the concept of aesthetic care. Just like fashion, beauty, as well, is a manifestation of our ego, a reflection of the nature, personality, passions, and beliefs of us, who make a flag of our inner reality out of our body. Beauty is a manifesto of our uniqueness, the extension of our personality, artistic and healing work on ourselves. Some people say that “hair and makeup” is a mere act of vanity, a shallow operation aimed at changing the image of ourselves into the one we want people to see. It’s a debatable point of view. Beauty is a much deeper concept, it’s the art of cultivating the beautifulness that’s within us in every way it manifests itself, in all the dimensions where it’s hidden; beauty is fishing out our buried, beautiful selves and nurturing them, guiding them while they emerge, bloom and become our essence and our calling cards.

Beauty moments are rituals, almost mystical, almost magical: they’re pieces of time in which we pause our most frenetic everyday thoughts that, whether nice or unpleasant, pop in and out of our heads and put our brains in motion at a stressing, unhealthy speed, potentially harmful for our whole organism. During these ritual and spiritual moments, through a series of actions, mixed with lotions, powders, fragrances, as though bewitched, we stop our real time and enter our own, personal, dimension, where it’s time to focus on ourselves, our physical and mental well-being. Thus, our beautiful selves can emerge, and we, back on Earth, do feel healed, defined. We’ve taken good care of ourselves, so to take better care of the rest.

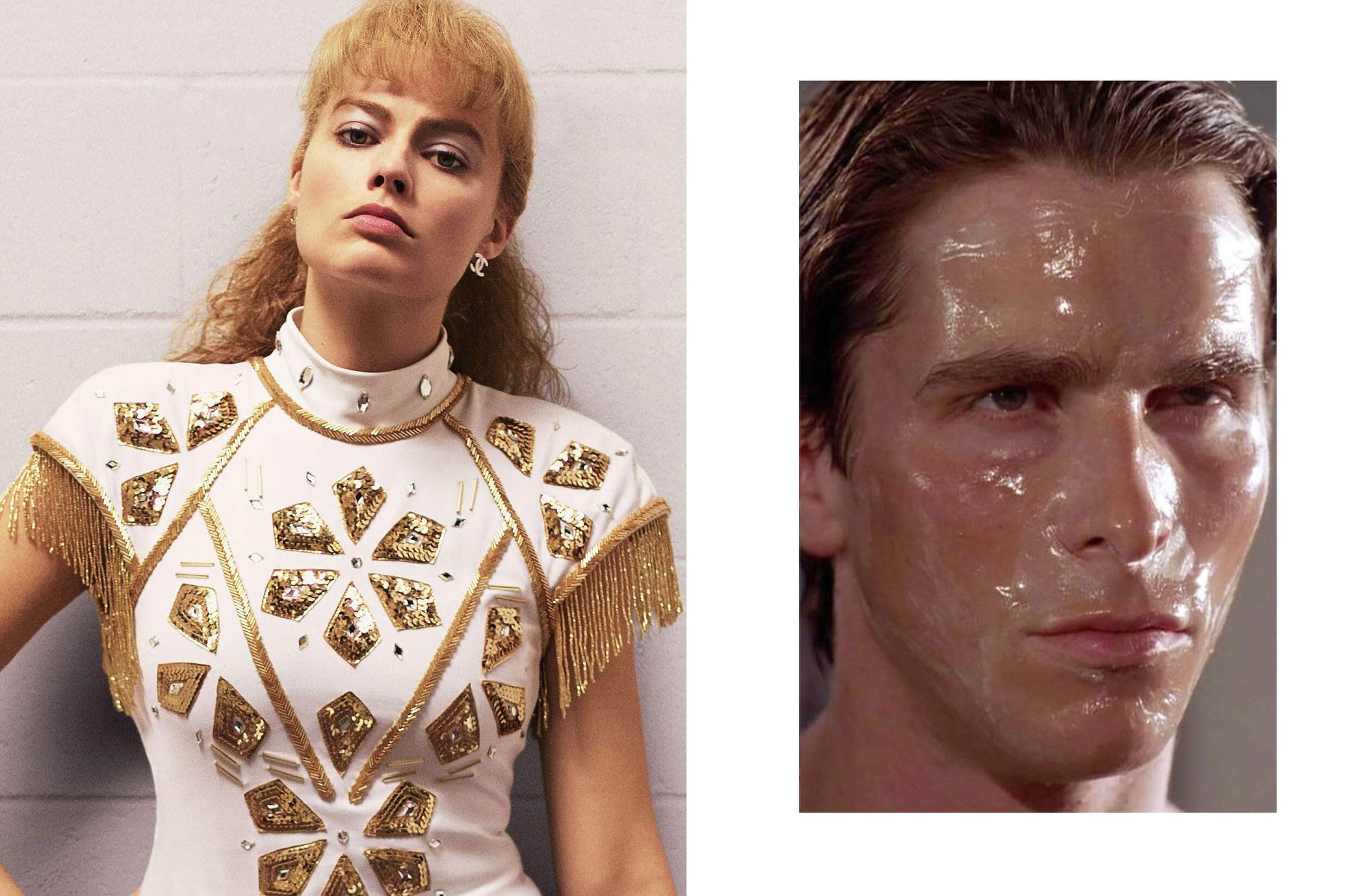

Cases where beauty is experimentation, cases where beauty is an expression, cases where beauty is preliminary, cases where beauty is transformation: a wide range of uses and applications for a widely represented concept within the scene of the celebration of the beauty that is cinema. The makeup and hair of a character are part of the fabric of its profile and necessary to it, an extension of their personality and motive for their deeds, as much as the path through which they get to certain specific aesthetic results. Just think of Patrick Bateman’s (Christian Bale) famous “skincare routine” in “American Psycho.”

“American Psycho” by Mary Harron (2000)

An eloquent ritual, that is enough to describe the character, a detail congruent with his nature. In the famous morning routine scene, where Bateman introduces himself and accurately describes every single step of his beauty ritual, naming the products he uses one by one, and performing each step as if it were a video tutorial. In his rich and splendidly furnished house, between the bedroom, the living room, and the shower, Patrick honors his faith in personal care and “a balanced diet and rigorous exercise routine,” outlining the first traits of the profile of a strong character, who will soon turn out to be an obsessive and psychotic man. The high point of the morning routine scene is the removal process of the exfoliating face mask, performed by Bateman with maniacal accuracy, almost like he’s getting rid of a skin layer, almost like he’s tearing his own face; not surprisingly, in that very moment, standing in front of the mirror, he confesses: “There is an idea of a Patrick Bateman. Some kind of abstraction. But there is no real me. Only an entity. Something illusory. And though I can hide my cold gaze, and you can shake my hand and feel flesh gripping yours, […] I simply am not there.”

On the topic of “strong characters” and beauty as an affirmation of their characteristic personality features, let us recall the belle-from-hell Charlotte from Tom Ford’s “A Single Man.”

“A Single Man” by Tom Ford (2009)

Played by an extraordinary Julienne Moore, Charlotte is an exhausted woman, drained out by her past experience, a tough woman, sassy, sensual, self-confident, but also devastated and tired; all these traits are highlighted and efficiently expressed through a bold and heavy makeup: eyelids decorated with thick, black kajal strokes, 1960s style, matched with bouncy, elaborate hairstyles. The sequences of close-ups show us her makeup looks and hair in detail as if they were essential threads of the film’s texture. In fact, they are.

An example of beauty rituals as means of disguise or dissimulation (of a bad mood) is Margot Robbie’s Tonya Harding in “I, Tonya,” the biopic about the real-life story of the famous former figure skater.

“I, Tonya” by Steven Rogers (2017)

Tonya Harding is a contradictory character, whose accusations of having commissioned the aggression of her rival before the Olympic Games forever marked her career, private life, fame, and physical appearance. That’s because our spirits can have repercussions on our body, skin, hair… The more Tonya’s life gets complicated, the more anxiety, stress, and frustration become visible on her body, as proved by Margot Robbie’s brilliant acting performance and the huge work carried out by the film’s makeup department. An emblematic scene is the one in which Tonya gets ready for a figure-skating competition, and she’s sitting in front of the mirror, putting makeup on her face: holding back the tears, trying to stay strong at all costs, she paints her cheekbones with a cherry blush stick, tracing some think lines almost like a Red Indian warrior painting his cheeks before fighting his enemy; while blending the blush with her fingers, in a series of violent taps on her cheeks, she almost seems about to burst into tears, but makeup is there to protect her, hide her, and it’s given her the courage and strength to relax her face in a frozen smile.

Just like Tonya, all dressed up and sitting in front of the mirror, similarly caught in the act of putting makeup on her face to get ready to face a challenge, we shell find the Grandma from “Loose Cannons,” Ferzan Ozpetek’s movie all set in the area of Lecce, Southern Italy.

“Loose Cannons” by Ferzan Ozpetek (2010)

A strong, offbeat, personality, the only non-conservative and open-minded member of a homophobic and traditionalist family, this character (played by Ilaria Occhini) figures out the most extreme plan to safeguard her family and its cohesion. She puts her plan into action starting with a preliminary beauty ritual: during one of the most touching and fascinating moments of the film, the Grandma sits at the vanity in her bedroom and, in the dim light, she puts some makeup on her face with accuracy and devotion: firstly, the eyes, with a blueish eyeshadow, then a black pencil on the lash lines, then a pink blush on the cheeks, and lastly, some glossy, peachy lipstick on the lips. Earrings on, and he’s splendidly ready to take action.

Caught putting her lipstick, getting ready, and scrutinizing herself in front of the mirror of a glacial, sad bathroom, is Marion (Jennifer Connelly) from “Requiem for a Dream.”

“Requiem for a Dream” by Darren Aronofsky (2000)

Her dark cherry lipstick and carbon black eyeliner mirror the gloominess of her spirits, as much as the carelessness with which she paints her lips, just because she needs to do it, just like she needs to do what she’s getting ready for. Her boyfriend, Harry (Jared Leto), rings her from the cell in which he’s been imprisoned because is a drug addict, and, in tears, he promises he’ll come back to her that very night, but he knows he’ll never come back; Marion knows, too, and a tear streams down her face, a drop that she promptly wipes off because if her makeup is ruined, if her face is wrong, her dream will never come true.

Another preparation ritual, preliminary to a (truculent) deed, is the makeup scene starring Buffalo Bill in “The Silence of the Lambs.”

“The Silence of the Lambs” by Jonathan Demme (1991)

Jame Gumb aka Buffalo Bill (Ted Levine) is a serial killer: he kidnaps young women to skin them and create a macabre dress as a sort of revenge against the system, as he was denied a sex-change surgery. A famous scene from the movie, one of the scariest and most emblematic starring the character, features Buffalo Bill’s beauty ritual; the number one step is a brown powder on his eyebrows, to thicken them, and then, necklaces and nipple piercings on in place, the lipstick: “Would you fuck me? I’d fuck me. I’d fuck me hard,” says the killer to a mirror, while painting his lips peach-pink, and his victim is awaiting trial, desperately looking for a way to escape. But he doesn’t care, he’s hypnotized, caught in a vanity charm, in a sensual dance in front of the camera, in a fictional ritual that, for a few, ephemeral minutes, makes him feel and look like what he wants to be.

Black nail polish on his toenails, red lipstick, and eyeliner on, plus an unsatisfied glance at his own image reflected in the mirror: this is the morning beauty routine of Cheyenne (Sean Penn) from “This Must Be the Place”.

“This Must Be the Place” by Paolo Sorrentino (2011)

It’s the beginning of the movie, the opening credits scene, the one that shows us a series of actions performed by the protagonist which can perfectly describe him, introducing him to the audience, still unaware of the past and present of the character and thirsty for details: Cheyenne is a retired rockstar who keeps dressing up and wearing makeup just the way he used to when he played gigs with his band. For several years, he’s been in self-exile in his Dublin house, where he spends his days plagued by depression and anxiety, disenchanted with the idea of the healing power of rock music. Once again, the character’s beauty routine, the products he uses, and the way he applies them on his face, can speak for him: black nails, red lips, and kajal put on with the aplomb and indifference of a rock god who’s lost his faith in his long-time cult.

Speaking of “beauty as preparation” for an imminent event or action, we can’t but mention one of the masters of aesthetics and experts in the celebration of beauty in films: actor/director Xavier Dolan and, specifically, the amazing beauty routine scene in his second feature film “Heartbeats.”

“Heartbeats” by Xavier Dolan (2010)

Two friends and rivals in love, Marie (Monia Chokri) and Francis (Xavier Dolan), both in love with the same boy, each convinced that he returns their love and not that of the other, and both afraid to be wrong, are in the process of getting ready for their love interest’s birthday party, meticulously, superbly, with a single common goal: to be liked, to be conquerors. While Marie, in her bathroom with red walls and warm lights, combs her wet hair, curves and paints her eyelashes with mascara, Francis, in his bathroom with white walls and cool lights, sprays his perfume on his neck, one spray for each side, scrutinizing his own image reflected on the wall and magnifying mirrors. “Bang Bang / And whoever strikes at the heart wins,” sings Dalida, in Italian, in the background, while Marie and Francis, makeup on and all dressed up, are ready to strike.

Beauty for “role-plays” belongs to theater, cinema, dance, and entertainment in general: beauty can reshape our facial features, improve them, make them worse, emphasize them, soften them, makeup can turn us into different people for as long as we want. It’s exactly a role-play what director Guido (Marcello Mastroianni) proposes to his lover, naïve Carla (Sandra Milo) in Federico Fellini’s masterpiece “8 ½.”

“8 ½” by Federico Fellini (1963)

“Your makeup needs to be more… slutty,” says Guido to Carla in the hotel’s bedroom. So, he takes a brush and smudges her face, painting thick and irregular strokes over her thin eyebrows. “Make a slutty face!” suggests Guido; “Do I look like one of your actresses?” asks Carla impertinently, exiting the room with her new, fake eyebrows, ready and willing to transform as she pleases.

“Beauty as a disguise” -wise, we could mention a couple of characters completely different from each other, but sharing the same use of makeup and/or beauty routines. Let’s start with the protagonist of the teen cult “Mean Girls,” Cady Heron (Lindsay Lohan).

“Mean Girls” by Mark Waters (2004)

A sweet and naïve girl, but obsessed with the desire and necessity to be liked by people – and by the cool girls in school in particular –, she wears makeup as if it were a superhero mask, to gain power, to hide her true nature and homologate to the standards and fashions followed and preached by her high school’s hit girls, whose success Cady would want to reach, even at the price of giving up her few, true friends. So, when they ask her to spend some time together, Cady opens up her pocket mirror, putting her trendy lip gloss on with a real snooty look, and declines the invitation, declaring herself busy with questionable activities that just can’t involve them.

It is with a similar purpose, but in different ways, that Arthur Fleck makes use of makeup: to put on a mask and hide, turning into someone else, in this case, the “Joker” by Todd Phillips.

“Joker” by Todd Phillips (2019)

Exaggerating and emphasizing the look that he’s forced to put up every day, to earn his living as a clown, a desperate and psychotic Arthur (Joaquin Phoenix) chooses hair dye instead of a wig, and a white-stained face instead of an evenly smoothed greasepaint: in this way, he changes his identity. In a beauty ritual in front of the mirror, we watch him writhe half-naked in an uncoordinated dance, while he soaks his hair in green hair dye and paints his face, eyes, and tongue with a brush dipped in greasepaint, preparing to become the cabaret artist he’d always dreamed to be. And, as the writing on the mirror of his fitting room reminds him to “put on a happy face,” Joker, with a smile painted red, wide enough to fill his chin, plays with his life and the lives of the inhabitants of Gotham City.