He starts a movie with a 1:1 scene taken by “Gone With the Wind” and he ends it with two-years-old videos of real reporters to demolish his positive and glorious finale just to demonstrate the necessity to tell a story, happened in the ’70s, which is dramatically contemporary.

“Disjoint is based upon some fo’ real, fo’ real sh*t!”

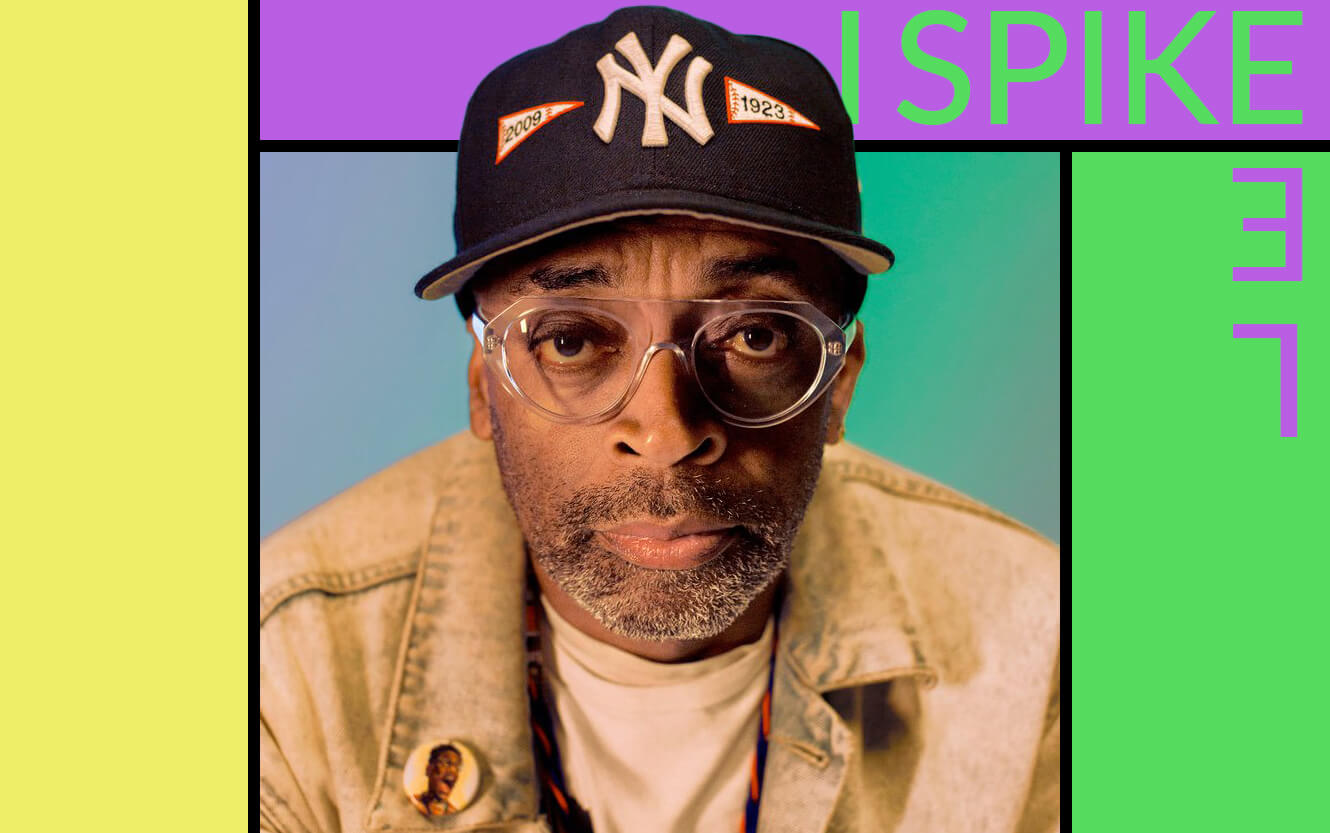

Then he incites the electors to get prepared for the 2020 elections, asking them to, “Do the right thing,” you know what he means, and yes, he did that exactly when he was receiving his first Academy Award (actually, it’s the second one, but this is his first one for a film in competition). Ladies and gentlemen, this is Mr. Spike Lee. A brave and angry director for at least thirty years. Then we face another Spike Lee’s political movie (please, take a look at the etymology of the Greek word ‘polis’), we face a sincere movie that takes an unmistakable position in terms of racism, ignorance, and history, we face a movie that doesn’t need any feel-good reconciliation or to wink to the audience.

The plot, based upon the real life of the policeman Ron Stallworth, is thorny: we are in Colorado during the ’70s, where a young man succeeds to join the Colorado Springs police force, and he’s the first black policeman in the history of the city. What is waiting for Ron is the vexations, oppression, mockery and the whole set of abuses that the average man can throw at him. He’s inexperienced but enthusiastic, assertive, clever and practical. His luck is to be flanked by colleagues, who are reluctant at the beginning then bravely following his instinct (can I say Black Panther instinct?), despite the first few evidence.

The excellent screenplay interchanges the white and the black side of the coin, flipping it constantly, giving light to every little spot, without filters. That’s why this film can be considered choral: because the good lines permit to some roles, generally considered small, to carry weight in the plot. Walter (an unrecognisable Ryan Eggold), Felix (Jasper Pääkkönen, disturbing and perfectly in character), Ivanhoe (Paul Hauser, so dummy, it’s good) and David Duke (Topher Grace) are the white suprematist supporting their world vision whatever it takes, as much as Patrice (a fascinating Laura Harrier), Kwame Ture (elegantly played by Corey Hawkins) and Jerome Turner (Harry Belafonte, the singer, involved in a long monologue) are the supporters of the Black Panthers’ ideals.

Mr. Lee doesn’t censure, as he never does, but tries to report accurately two schools of thought that collide by definition, in a spiral that faster and faster ties itself up, or rather, snarls up. That happens in front of us thanks to the duet of undercover agents: the excellent John David Washington (always perfectly groomed) and Adam Driver (this time in the difficult role of an apathetic character). They interchange under the name of Ron Stallworth in a complementary manner, and they have to make a carbon copy of Ron: a white one and a black one.

An authentic black man with a white face!

There’s a hilarious and unforgettable phone call between David Duke and the black Ron, during which the founder of the Ku Klux Klan praises black Ron for being a real white American man, where you can appreciate John David Washington’s pronunciation of what is considered real American words. The following sequence of misunderstandings is as funny as it’s frightful. Tension and laugh pleasantly alternates in a crescendo that ends in a cathartic and quite touching finale (with the help of the music, composed by Terrence Blanchard, once again at work with Spike Lee) where reconciliation between black people and white people isn’t expected, because it didn’t happen in the ’70s (and maybe we don’t have it today, as well). The first one who decides to shoot is the first to fall, dying because of his own mistakes. This is a Spike Lee joint, not a Peter Farrelly’s. Mr. Lee used up all his feel-good vibes in primary school.

I find the representation of life inside the police station really convincing because, in the screenplay, this becomes a sort of a microcosm, a mirror of the reality they live in the streets. It’s a frame wherein all the plot is developed: it opens and closes the movie just to remind us that this is the story of a policeman.

Some colleagues mock Ron for the color of his skin, some others try to hinder his investigation, others are ready to help and in the end, the chief, who was looking from outside, recognizes the value of Ron’s job, coming to punish the most sadistic of his subordinates. I’d like to applaud something else, in conclusion: the dialogues, ready to activate the short circuit, another praise for the casting director Kim Coleman, competent in choosing interesting faces and dense interpretations for every role up to the less important.

The second to last appreciation should go to the costumes (by Marci Rodgers) because she set up two uniforms, perfect for underlying the polished look of the black community (with black leather over popping colors and the shabby one of the white supremacists, all wearing hunting trousers and plaid shirts as if they were a legion of woodsmen. The last approval is for the direction: the camera is always in a precise place from where we can see every detail, in a moment it’s set perfectly balanced, but in the next frame it’s tilted a bit, just to enlighten some amazing moments as they happened.

Thanks, Spike: even if you persist in supporting the Knicks I really love you because you were never one to mince words. You spat them in our face in every film you did, and I hope that this time the audience will be able to understand the urgency of telling the events of a fu***** ass**** with his group of exalted against a black, smiling policeman full of ideals at risk of extinction.

I Spike Lee!

Cover Credits: Time Magazine