There are books, and then there are THOSE books.

Those that you can’t stop reading, that manage to transport you with such realism in a story to believe for a few moments that you really are in a certain setting: in my case, among THOSE books, there is the saga of “The Chronicles of the Maple and the Cherry Tree” by Camille Monceaux. A coming-of-age story, a protagonist who, in pursuing the “way of the sword” to become a Samurai in feudal Japan, reminds us how our path has not yet been defined, how every turn can change us, and how the people with whom we travel the road, and the emotions we feel in the meantime, are essential to fulfill our destiny.

Although the setting could not be further away, Camille has managed, through her writing, to give life to a story that speaks of the importance of feelings, of knowing how to accept loneliness and be patient when it comes to heal (both spiritually and physically). Even if the chat with Camille was done standing, surrounded by the many people walking around, it seemed that there was nothing else outside of her, me, and the beautiful and rich conversation we had: from the value of the messages that each story contains to how different cultures make us aware of the uselessness of stereotypes, from the world in which she and her characters have influenced each other to the importance of embracing one’s limits and finding one’s family everywhere.

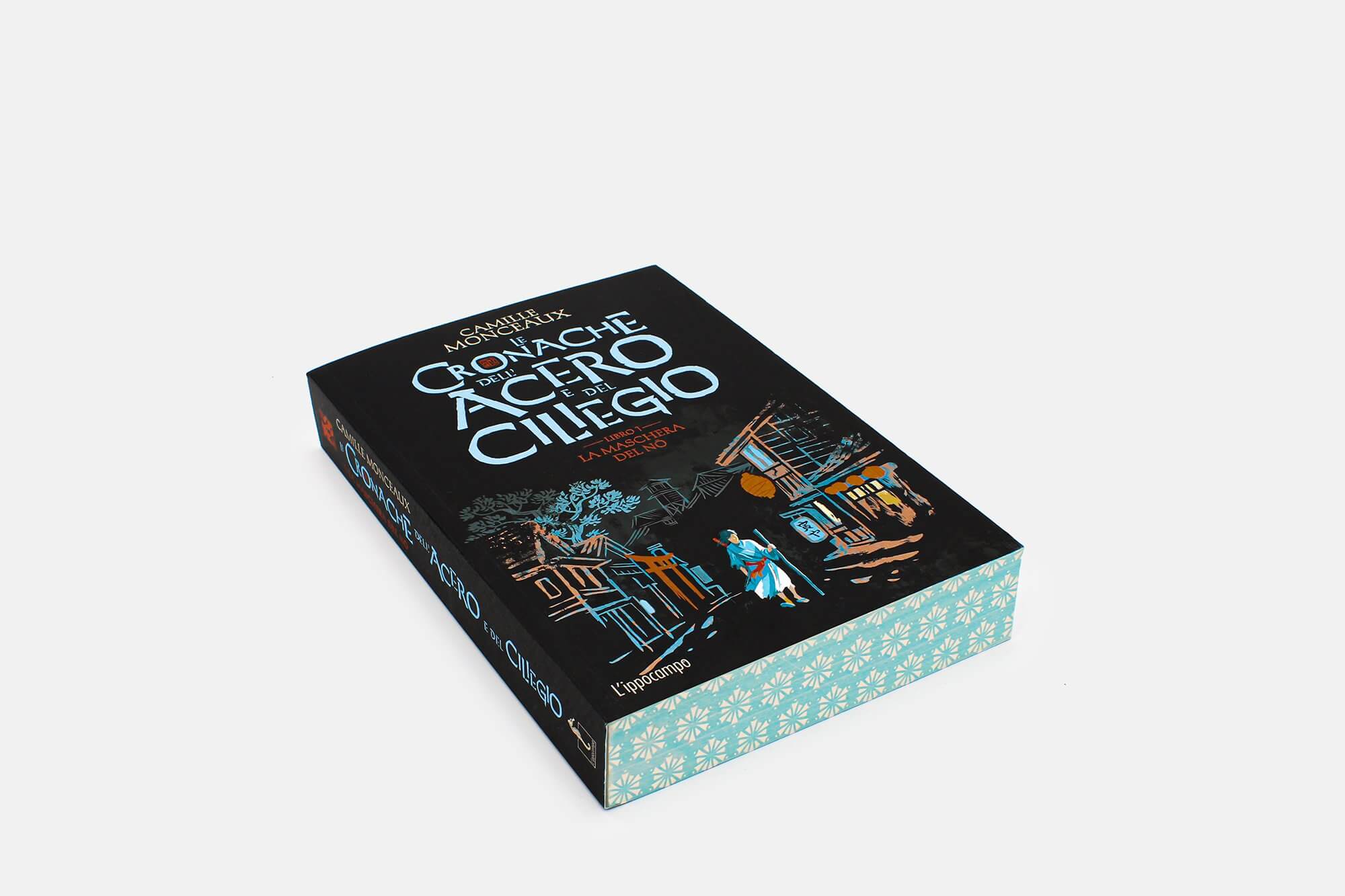

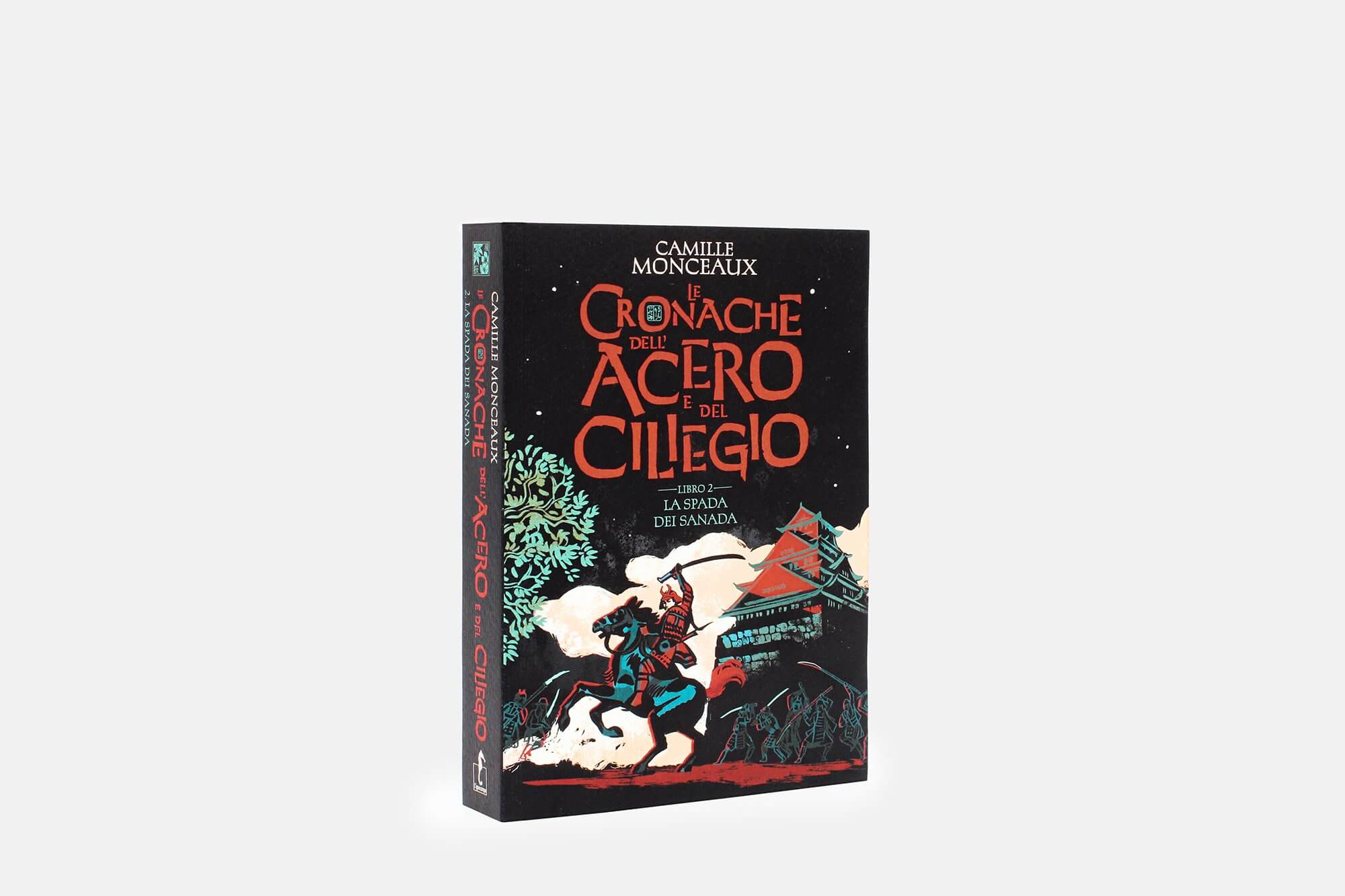

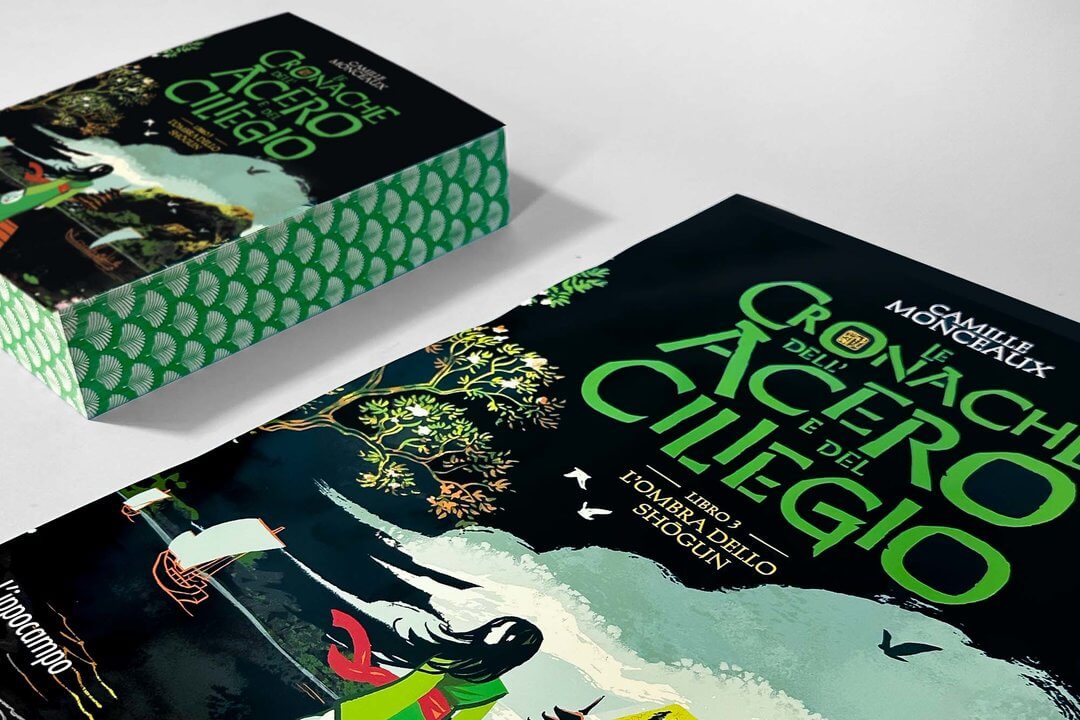

While waiting for the imminent release of the third volume of the saga of “The Chronicles of the Maple and the Cherry Tree,” this interview stands as a collection of key concepts to read and keep in mind while, together with Ichiro and his friends, we discover what the “way of the sword” will reserve for us, which is nothing more than ife itself.

First of all, I would like to thank you for this beautiful story and word you’ve created; the first book was one of the best that I’ve read last year, and I’ve finished the second one in two days! Have you always wanted to be a writer? Do you remember the moment when this vocation caught you?

I think it started when I was very, very young. I’ve always been in love with books, but it was maybe when I was about 7 or 8 that I understood that there were stories and people writing the stories, and that’s when I thought that I wanted to do that, too: write stories myself. So, it’s been my dream for a very long time.

I’ve written secret diaries for many years, but I haven’t really started writing novels until I had a computer. When I was in school and university, I knew that I wanted to try and be a writer, but everyone around me, especially the teachers, kept telling me, “Don’t you even bother trying; everyone wants to succeed and become a writer, and you will never get the chance to be published”. So, for a very long time I’ve had that idea in my mind that it was not even worth trying because it was too hard. Anyway, one day I thought, “Fuck that, I’m going to try and send what I’ve written to publishing houses, and if it doesn’t work, so what? At least I’ve tried”.

About the book, I’ve had the feeling that this story is so far yet so close, in terms of both place and time. How did you manage to create an atmosphere that feels so real, and how did you balance the research to write such an historical and precise story with your own inspiration and creativity?

First of all, thank you because it’s always very nice to hear that people are settling into the novel and that I’ve succeeded into creating an atmosphere. It’s very hard for me to balance historical research and fiction, and I tend to linger too much on research and I want to put everything into the novel, but I’m very lucky that my husband is my first reader; every time he reads my novels, he makes me notice what maybe isn’t relevant to the story. I’m very thankful for this because otherwise the novels would be a thousand pages long and sometimes with not very interesting details; but the thing is, I find it’s very fascinating to know little details about how to make some kinds of dishes or to wash the clothes in medieval Japan, for example.

I studied history and Japanese literature at university, ever since I was in high school, I loved historical fiction and historical movies, “The Gladiator” is one of my all-time favorites, and that’s because I love to try and picture how people lived in the past, like in Ancient Rome, in the Middle Ages in Europe, in the Middle Ages in Japan, how people lived, what they thought about, what they ate, what they looked like, what was considered beautiful and what was considered ugly, if nudity was a problem or not. I think that’s so interesting, especially when you are a feminist, and you want to try and show that everything we think about how women and men should be is just a social construction, and when you study history from different countries, you realize it even more. For example, in Japan female beauty focused on having white skin, shaved eyebrows, black teeth, which is something I don’t find especially sexy, but for them it was absolute beauty. This means that what you think is beautiful is actually just a construction. I try and put that into my novels. Maybe that’s why I don’t believe that literature and young adult literature, in particular, are apolitical, I think they have a message to deliver. Even though I speak about feudal Japan, mine is a way to try and have more inclusive stories and feature LGBT representation, and have a feminist point of view on history.

Some authors say that they don’t put political messages into their novels: I’m sorry but I don’t buy that, for me it’s not true, every novel has a message because of who you are, you are a message yourself, so what you write is already a message.

Speaking from an Italian-point of view, I had the feeling, in the last years, that there’s finally an opening to YA stories inspired by the rich possibilities given by the Orient, I’m thinking for example about “The Poppy War” and “These Violent Delights.” Did you have the same feeling while writing yours? Even though, more than a YA, it’s about the literal formative road that Ichiro pursues over the books.

I’m 32, and I think mine and yours is a generation raised with manga and anime, which I know to be huge in Italy and France. So, obviously they’re a significant influence, and nowadays, with globalization, I think we’re lucky enough to be able to open up to different cultures. Still, for a while I’ve felt uncomfortable thinking, “I am white female, so should I write a story about Japan even though it’s not my culture?”. I wasn’t born in Japan, I can speak and I can read Japanese but I’m far from fluent, so I wondered whether it would have been cultural appropriation.

Some people think that everyone should be able to write about whatever they want because of the principle of freedom of speech; however, I don’t agree. I think we should be very respectful about the cultures we are speaking about, and I don’t want to use a neo-colonial approach towards Japan and Japanese culture for example. I think we love the Orient a lot, and especially when I was younger, Japan was really a big thing; today, instead, it’s more about Korea, just think about the K-Pop that’s going strong. I started watching Korean dramas not so long ago, and I fell in love with that genre, and this made me want to start studying Korean culture.

I think it’s a fine line to walk on between falling in love with a culture and wanting to write or create something about it, while still respecting the culture.

What was the most interesting fact that you discovered about Japan through this story and atmosphere and that made you fall in love with this culture even more?

That’s a very good, interesting and hard question [ride]. A detail that was really shocking, about something I didn’t know, and that made me fall in love even more with Japan, is that nudity wasn’t as much of a problem as it might be for us today. There was no Christianity there, and no monotheism, and although Buddhism was very strict about gender roles, for instance baths were open to both men and women together, and you did a lot of jobs half naked; there are lots of representations of Japanese men wearing only a small cloth and walking half naked in the streets, and women showing their breasts. All this was not sexualized, that’s just how they did their jobs, carrying heavy loads or stuff like that. I found that really interesting and it made want to travel back in time and go to Ancient Japan because it was very different from today. Another thing that shocked me is that divorcing was a really easy thing to do in feudal Japan; you know, you got married simply by exchanging three cups of saké, and then if you wanted to break up, you just broke up. In the same era, but in Europe, it was impossible to divorce, on the other hand, especially for women.

Itchiro is following his “way of the sword”. Are you pursuing something similar in your life as well, both as a person and a writer? And if so, what are the main satisfactions and difficulties in doing so?

My own “way of the sword” is definitely ashtanga yoga, which is a type of yoga including a series of postures and you practice every posture every day. You have a series of postures for beginners, and then when you get better you start with the second series. So, you are supposed to practice it every morning before dawn, with an empty stomach for one hour and a half; you meditate, breath, and then you start your day. I did that for three years, waking up very early every morning and practicing my postures; it was amazing, it made me feel very powerful in my body because it’s a very physical practice and also very meditative, of course, so it was empowering. I was doing it to get stronger and be the best I could, but I realized at some point that I was doing it for my ego; I started feeling stressed out, not getting enough sleep, and developed sleep anxiety. Furthermore, I found it was a military discipline created by Indian men for men, it was a military routine to train soldiers, which made me wonder, “Is it really what I want? Do I have to be so strict about it?”. Now, my routine has changed, I’m not practicing yoga every morning, also because I realized that when I would do that, it was a way of being very strict in my relationship with my body, and toxic, it was almost a masculine toxicity. I realized I had to be more laid back and find a better balance between my practice and what my body is able to give. I need to be able to say, “Okay, today I’m not feeling well, so my body won’t be able to practice for one hour and a half, and that’s okay”. Last year, in October, I had a pretty bad injury, I broke my ankle, so I couldn’t do any sports for six weeks, I was in bed and I couldn’t stand up, and I was so scared that I would have lost my strength; this happens to Itchiro, as well, he gets injured in book one, and in book two he tries to recover at the temple, but I wrote it before I got injured myself; you know, in the book there is a monk who says that you need to be patient, and I thought about that a lot when I was unwell, it was amazing that my own books were helping me! [laughs]

The mask of the NO, related to the theatre and art, and the Sanada sword. Passion and duty. Emotions and honor. Ichiro struggles all over the story between these two antipodes. What do they reveal about the characters of this book (because I’m thinking also about his friends and other Samurais in the books), and maybe, about you too?

There’s a lot of myself in Itchiro, I’ve put a lot of my personality into him. We share the love for nature, for example, we’re both vegetarians – I’ve been a vegetarian for almost 8 years now, and I couldn’t imagine having a hero who eats meat. I wanted to write a story about a Samurai, but not a super badass Samurai who’s going to kill everyone and be the strongest of all; I wanted my character to feel the conflict between his softness – he’s very tender, he has a big heart, he cries a lot – and the way his master raises him to have no emotions. It’s interesting because that’s the point of yoga, to get rid of your emotions and your ego and just be in a perfect state of mind and awareness. Unfortunately, I think that this “way of the sword” was often linked with violence, and the idea that the royal cast had to own all the power exerting violence on all the other people, but I didn’t want Itchiro to become that guy.

Who’s the character that you can relate the most up to now? And, while wiring them, did they surprised you somehow, did they made you discover something new about yourself?

I think there is a little bit of me not only in Itchiro, but also in Shin, and also obviously in Denchai, the poet. There are some things about me in every character. I cannot say too much about my third novel without making any spoilers, but both Itchiro and Hiinahime are two different versions of me, basically. When I was a kid, I wanted to be a boy: for many years I’ve tried to pee standing up, and I was always acting like a boy, I didn’t enjoy dressing up like a girl, etcetera. My dad was a hunter and I often went hunting with him, so I was raised in a kind of classical masculine way. I wrote Itchiro the way I did because he’s a version that maybe I could have been if I was a boy.

Itchiro and Seiren are, in the second book, the characters that most struggle with who they are, and who they want to be, although in two totally different ways. And they are still so young, so the feeling is that they should be allowed to experiment, to get lost, to find their purposes, but the circumstances (and the context) don’t let them do so. Finding yourself: is it possible for you? Is there and end to the process, or is it more a never-ending journey?

I think it’s a never-ending journey. I definitely believe that throughout your life you are going to experience different types of things that are going to make you change, and you need to adapt to those changes. For example, for me ideally the older you get the wiser and the more tolerant you should become, but the truth is that the older you get, the more conservative you get – you do not want to change, you do not want to accept that young people think differently than you; I hope I won’t be like that, I hope I will be changing throughout my whole life and always listen to what younger people think and try to teach me. In the novels, there will be an end to the journeys because it’s a fictional story, we’re not going to follow the characters throughout their whole lives, but there will be an end in the sense that I want them to succeed in finding their own selves.

When I became a feminist, a vegetarian, and also climate aware, I started thinking, “I wasn’t raised like this, my parents were not like this”, I had to do it all by myself. For a while, I’ve felt torn between my education and what I felt was right, so I started changing my habits and myself a lot; and I think it’s the same for Itchiro, he was raised as a Samurai, he’s supposed to become a violent killer, and he loves his master, but that’s not the kind of person he wants to be, and the same goes for Seiren.

I love both characters and I had so much fun writing their debates, and I think the story needed a character like Seiren, who’s a badass also in a bad way, making Itchiro stand out saying, “It’s not cool to kill people”, and thus changing the trend, in a way, as it’s usually the female character who says things like those.

Itchiro is part of a close group of friends, and of a clan, but there’s a solitude within him that never go away, and it was something that he was probably able to share only with Hiinahime. Being a part of something and being on your own: how do you manage these aspects, both essential for mental health by the way?

One of the main topics of the third book will be solitude, which I think got heavier and heavier because I wrote that book during Covid, at a time when a lot of people were feeling lonely, and I was feeling lonely because it was just me and my husband and we couldn’t see a lot of people, we were supposed to be traveling and we couldn’t anymore, my sister was living by herself and she struggled a lot with her mental health. So, that was a very important issue for me. Also, when I was younger, in high school, I had friends, but I felt lonely very often; maybe, when you’re a teenager, you can very easily feel like nobody understands you and you’re the only one feeling that way. Sometimes, I felt very different and it was hard for me to feel like I fit in, so loneliness was for a very long time something that I had to deal with. I managed to get better the day I learned to be happy being just by myself; sometimes you can be in a room full of people, even friends and family, and still feel so lonely.

Sometimes, loneliness is not a physical act, it’s not just about being alone in a room, sometimes it’s feeling alone in your mind, it’s feeling invisible.

I love Itchiro as a character because he’s a great way of representing someone who doesn’t know anything about life around him, and a great way of raising topics such as how to deal with loneliness. I don’t know if I have the perfect answer to that, but now, at 32, I love having lonely moments, I love being just by myself, but also having the feeling of being excluded in a room full of people feels very hard. That’s why it’s so important to find your own family, made of people who understand you and accept you the way you are, and this is what I’m trying to do in the novels.

What’s the book on your nightstand right now?

I’m reading “Nous sommes l’étincelle” (“We Will Be the Spark”), a novel by French author Vincent Villeminot, about climate change, set in France 60 years from now in the future, after a sort of collapse. It’s very beautifully written.

Itchiro is always on the move, in a journey that, up to know, seems to have to end. What’s instead your happy place, where you feel like belonging?

I’m happy when I travel. I love travelling, it’s a very important part of my life. I haven’t had a real home for almost five years, I wrote the first book when I was in New Zealand, living there with my husband; perhaps, that’s why also the characters in my novel are traveling all the time. I just love being on the road, but at the same time I know that being on the road sometimes makes me feel homesick, and a part of me can’t wait to have a home, a place that’s only mine, but I’m also happy to be free and to be able to go wherever I want. So, I would say that my happy place is wherever I am with my husband because he’s the person I love the most in the world, he’s my best friend, we’re always together, so as long as he’s next to me, I know that I’ll be fine.

Thanks to Ippocampo Edizioni