The world of cinema and theater is one where stories intertwine and manifest through a common language, the language of art, made of honesty and experimentation. In this world, Dajana Roncione emerges with a strong and clear voice. Her career began on the theater stage and branched out into cinema, filled with a love for writing and expression that grows with each project.

Speaking with Dajana, I clearly perceived her essence, her passion for the honesty of storytelling and its transformative power, where the connection with the audience becomes a vital element.

Through her latest roles, from Giuli De Rosa in the TV series “Vanina” to the theater production “Sleeping Beauty,” Dajana takes us on an intimate and introspective journey, reflecting on the importance of writing in her life, the balance between rationality and instinct in character interpretation, and how certain deliberate acts of rebellion can become vital acts of personal freedom.

What is your first memory related to cinema?

Actually, I started with theater, so that was my first “opening.” Certainly, the Silvio D’Amico Academy, with its 8 hours a day for 3 years, made me realize that I was in the right place and that I wanted to do this job.

The first play I did, debuting as the lead at the academy, was “The Kitchen” by Arnold Wesker, directed by Armando Pugliese. It’s a very choral and dynamic text, in which one of the protagonists is a man, but Armando Pugliese decided to make two versions of this play, one version with a male actor and one with a female actress. And he chose me for the role of Peter. During rehearsals for the play, I cut my finger because I had slammed the serving dish too violently, and my finger was bleeding, but since the text also had Peter’s character cut his hand at one point, it seemed like a scene within a scene. I remember being struck by this synchronicity and that for me, it was somehow significant on an interpretive level to visualize that real moment, made of real reactions and real agitations, which could almost be confused with the representation of that text. I was fascinated to see life mixing with the text due to an accident, making it inevitably more interesting. From that day on, I have always welcomed accidents in theater as a “blessing.”

But my first true opening was at 16 when, during high school, I chose to take part in acting courses where we studied some great playwrights. The first year we worked on “Romeo and Juliet,” which was a text I knew and which, at 16, seemed completely honest to me in its depiction of the emotions of love. Since in life we struggle to be honest in relationships, especially when we are young and still do not know ourselves, as we have to defend ourselves and play roles, understanding that through theater, with a well-written and honest text, you could have the opportunity to live that moment without shame and without defenses, was the first true love for this profession for me. Clearly, this is true for cinema, as well, which has a different language, though, more detailed. When I discovered cinema, I was fascinated by the fact that I had to try to find that kind of communication in the details, in the small things, which was definitely more challenging coming from theater.

Maybe, after all, my first love was writing: for me, writing is the main element. When you come across words that truly go deep into emotion and are not superficial, that is when I feel the desire to make them mine, to perform them, and share them. This is the reason that convinced me to do this job.

“When you come across words that truly go deep into emotion and are not superficial, that is when I feel the desire to make them mine, to perform them, and share them.”

What you say about honesty is very beautiful. When you recognize it in a project, it is perhaps the element that attracts you the most.

Yes, I deeply believe in the honesty of writing. I believe that all those projects that we love have strong writing that goes deep inside concepts and characters. For example, “Anatomy of a Fall” is not a particularly beautiful film aesthetically, nor has it been economically expensive, I suppose, but what struck us was the screenplay, how deeply they delved into the psychology of the characters and the emotions of the characters. That has significant meaning for me as an actress. Moreover, coming from theater, where you always confront writers of a certain kind, you educate yourself to a different demand from writing.

The characters that struck me the most while studying at the Palermo theater, such as Antigone or Medea, are all characters with very strong emotions and actions that involve you: you feel the character, you feel what they are experiencing from the writing. For me, imagination is born from the text, from reading in general.

Since I was a child, I was interested in cinema: I liked “unordinary” films, and I had teachers who made me watch old films because it was important to them that I knew the history, films that were perhaps difficult to understand but which I was fortunate enough to see with people who explained them to me. Even there, the power of the image, combined with writing, for me, was a kind of ecstatic escape. I watch lots of films, lots of TV series, and I read a lot, so I have always been fascinated and attracted to this dimension, and being part of it is a great reason for gratitude for me because it is a privilege to do this work on a human level, as it allows you to connect with many inspiring situations that make you grow.

It is a job that brings together different people who work together for a period and have a common goal, and you hope they get along well and create an intense, productive, artistic relationship. When the film or project ends, suddenly all those people you saw every day are gone, and I immediately feel as if I have lost something because it is hard to detach from the micro-family you created for a while.

This is especially true for independent films, where you are there with your ideas supported by a group of like-minded people and there are fewer mechanisms at play. Usually, the main reason that drives me to do a project is the love and desire to share something beautiful, without other dynamics in between, and this type of work is what I prefer, with everyone fighting for a common goal.

In your latest project, the miniseries “Vanina,” you play the divorce lawyer Giuli De Rosa, a complex and multifaceted character. What attracted you the most to this role, and what made you say yes to the project?

I find myself in a moment of great artistic openness, at this moment. It had never happened to me before, except briefly with “Io sono Mia” where a sisterhood relationship with Serena Rossi was created, to have to play a friendship relationship with another character, Vanina. I liked the idea of being able to tell a female friendship and that my character had comedic aspects, which doesn’t happen to me very often. When I did the auditions, I discovered I had a comedic side that I didn’t expect [laughs]. I find well-done comedy much more challenging than tragedy, and acting with that energy is difficult because you have to find your own energy from the start. So, I saw this show as a challenge, an additional artistic step that I was interested in exploring in the complicity with Giusy [Buscemi], which we found from the first audition. I then found myself on a set full of such people: Davide Merengo and Giusy drew people in with their warmth, humility, and openness to what everyone could bring. On set, I felt there was a different, collective spirit that fascinated me, where everyone wanted to give their best. It’s wonderful when you feel that you work together even with people who have more individualistic attitudes, but in some cases, like this one, which was a collective work, it was important to have the support of the team.

The success of this series, in my opinion, also depends on this palpable teamwork.

“I liked the idea of being able to tell a female friendship and that my character had comedic aspects”

What were the biggest challenges you faced in playing Giuli and what were the best things?

The character has themes that fascinate me as a woman and are dear to me. In this first season, there is a transition that Giuli has to make in her personal life as well as in her professional life, which is also her strength and the fun part that helps Vanina distract herself. I also like that all the characters have wounds they need to heal to understand who they are; I find it interesting that a TV series allows the audience to see themselves in them.

What is the last thing you discovered about yourself through these two projects?

There was a moment when I felt a bit less artistically free; clearly, something in my life made me feel less open and less free, which led to more fear. Most of the time when I act, I am almost “obliged” to push beyond my fears. Even in the recent play I did, “Sleeping Beauty,” written by Carolina Balucani, which won a prize at the Biennale College in Venice, my character faced a beautiful theme of being almost childlike or not being trusted enough by others; by entering the dream of another character, she does exactly what she was afraid she couldn’t do – she becomes the character’s mother. This was a stepping stone for me, as I am not a biological mother, and it opened my eyes to aspects of myself I had been afraid to explore.

The theatrical act that exorcises the feeling allowed me to confront a theme that felt unclear and helped me understand many things.

The play “Sleeping Beauty” directly involves the audience by inviting them to participate in the initial party. How does your performance change knowing there is a direct interaction with the spectators?

I come from a very classical theater background, but I have always been a fan of Fabrizio Arcuri. When I went to see his shows, I was always struck by the authenticity of the actors and their constant active contact with the audience. I love Pirandello, and I believe that in “Six Characters in Search of an Author,” he tried to ensure that the audience didn’t fall asleep but felt active in the conversation. When I discovered this type of theater, it was a revelation for me; I felt it spoke to me the most. I adore having contact with people; I could stay on stage for hours because it’s an incredible emotion.

I remember a moment when there were soap bubbles on stage, and I thought to push a bubble toward a spectator: a very intimate moment was created when the bubble burst, and we looked at each other, and I felt an infinite energy. The beauty of it is that you never know what will happen because it’s not just you; it’s you with the audience, and you never know what will occur. It’s almost a performative aspect that makes you feel alive: you can’t help but be constantly alive on stage, even though – and perhaps precisely because – sometimes things can get dangerous and uncomfortable, both for the actor and the spectator.

“…you can’t help but be constantly alive on stage, even though – and perhaps precisely because – sometimes things can get dangerous and uncomfortable, both for the actor and the spectator.”

The plot is symbolic and dreamlike. How did you enter your character’s world?

I let the text gradually suggest and surprise me, so I focused on being present in the moment while acting. The play tackles very important themes, treated with masterful sensitivity and intelligence. Moreover, the director helped us work so that we were beyond the wound we were experiencing, so there was no lamentation or egocentrism about the pain – quite the opposite. The power of the text was its unabashed expression of feeling; it made it explicit, yet we worked as if we were a bit beyond the pain.

I went to see “A Little Life” in London, and both before it started and during the breaks, the actors went over their lines on stage in front of us, talking to each other and doing their exercises. This really struck me and made me feel even more a part of the show and the characters.

In London, there are many productions like this, with continuous audience interaction, which I think is necessary, just as the distance is, from which you can understand so many things. To this day, artistically, I prefer to have contact with the audience; I see that they engage better in a situation where they feel involved and active. Among all playwrights, Pirandello is the experimenter whose work particularly fascinates me because he seeks to do just that.

Do you write? How important is writing to you? Does it play a role in your daily life or only in your work?

Yes, I have always written in my daily life.

When all my thoughts accumulate, I feel the need to organize them and create distance to see them clearly, and I do this through writing. Whenever there’s something I can’t resolve, something that makes me feel bad, or even something beautiful, it instinctively comes to me to write and reread it and then leave it there without building on it. However, it’s not a constant practice; I do it when I feel like it. During the pandemic, for the first time, I wrote a treatment for a series about Tina Modotti, a revolutionary photographer I have always been passionate about. I’d been working on this project for over ten years until I decided to try proposing something creative based on all the research I had done about her. But if I was going to propose something, I also had to put on paper everything I had in my head, which I did, and it was a beautiful experience. It’s an ambitious project, and I’m happy I did it: it showed me that passion for something leads you to discover new things because since then, I haven’t been able to write anything else; clearly, it was for her that I did it that time, and I don’t know if it will happen again.

“When all my thoughts accumulate, I feel the need to organize them and create distance to see them clearly…”

As an actress, how do you approach the creation and understanding of a character? Are you more rational or instinctive when preparing?

Actually, I’m a bit contradictory because, over the years, I’ve realized it’s better to turn off my brain and listen to my body. I am quite physical as an actress, which I understood later, and indeed my instinct works much better than my head. However, I need to create a minimal structure and have a basic idea; I always work with a coach, Lucilla Miarelli. I’ve always studied, even after the Academy; I’ve taken masterclasses because I believe everything can be useful. There are moments when I think following an acting method is important, other times when I just want to be present in the moment, and other times when I need to feel my thumb trembling or seek eye contact with my scene partner.

Ultimately, it’s important for me to feel alive, and whatever helps me feel alive, I try to do it. One of the things I’ve discovered lately, even though I already knew it deep down, but perhaps out of laziness I hadn’t been doing, is that I need to dance before an audition or before filming until I feel that I’m in the moment. Only then do I feel open and free.

I try to find things that help me not to be in my head but to be present with everything that’s happening, because only then does everything else work.

What is the last film you saw that stuck with you?

“Perfect Days.” The gaze of that actor will stay with me forever; there is a whole world in that face. A wonderful, beautiful, pure, elegant film.

What book are you reading, or one you would recommend?

I’m a fan of Murakami, and right now I’m reading “The Writer’s Occupation.” Some books that have marked me are “The Art of Joy,” “1984,” and “When the Body Says No” by Gabor Maté, which have worked on my need for freedom, helping me understand how I can be free.

What has been your greatest act of rebellion so far?

It happened about four months ago. I don’t know if it was the biggest, but it was certainly the one everyone noticed. It was as if a cork exploded. I am very polite and attentive, and I think I have repressed my anger in many cases, even when I had the right to say, “This doesn’t sit well with me.” Then one day, I had an uncontrollable explosion, like superheroes discovering their powers and not knowing how to control them [laughs]. I think it was a moment of healthy rebellion because I evidently needed to allow myself some “no’s” that I had been holding in for a while. At first, it was strange, and it was for others too, but it was liberating because now I feel much freer and have found balance. Sometimes, I think it’s necessary to rebel or listen to that voice that says, “Enough, this is a limit, and I can no longer say yes.” We live in a complicated historical moment where there’s a tendency to be afraid, especially in the workplace, where you think it’s always better to be kind and accommodating. However, some things are imposed on us, which, as we mature and reflect, we recognize as wrong.

Now I can balance my kindness while being firm on certain things that used to consume me: I defend myself more thanks to this act of rebellion.

“…I evidently needed to allow myself some “no’s” that I had been holding in for a while. At first, it was strange, and it was for others too, but it was liberating because now I feel much freer and have found balance.”

What is your happy place?

I am Sicilian, and when I think of something that makes me happy, I think of the sea and the sun, which represent my origins. Also, my husband; when I’m with him, I am happy.

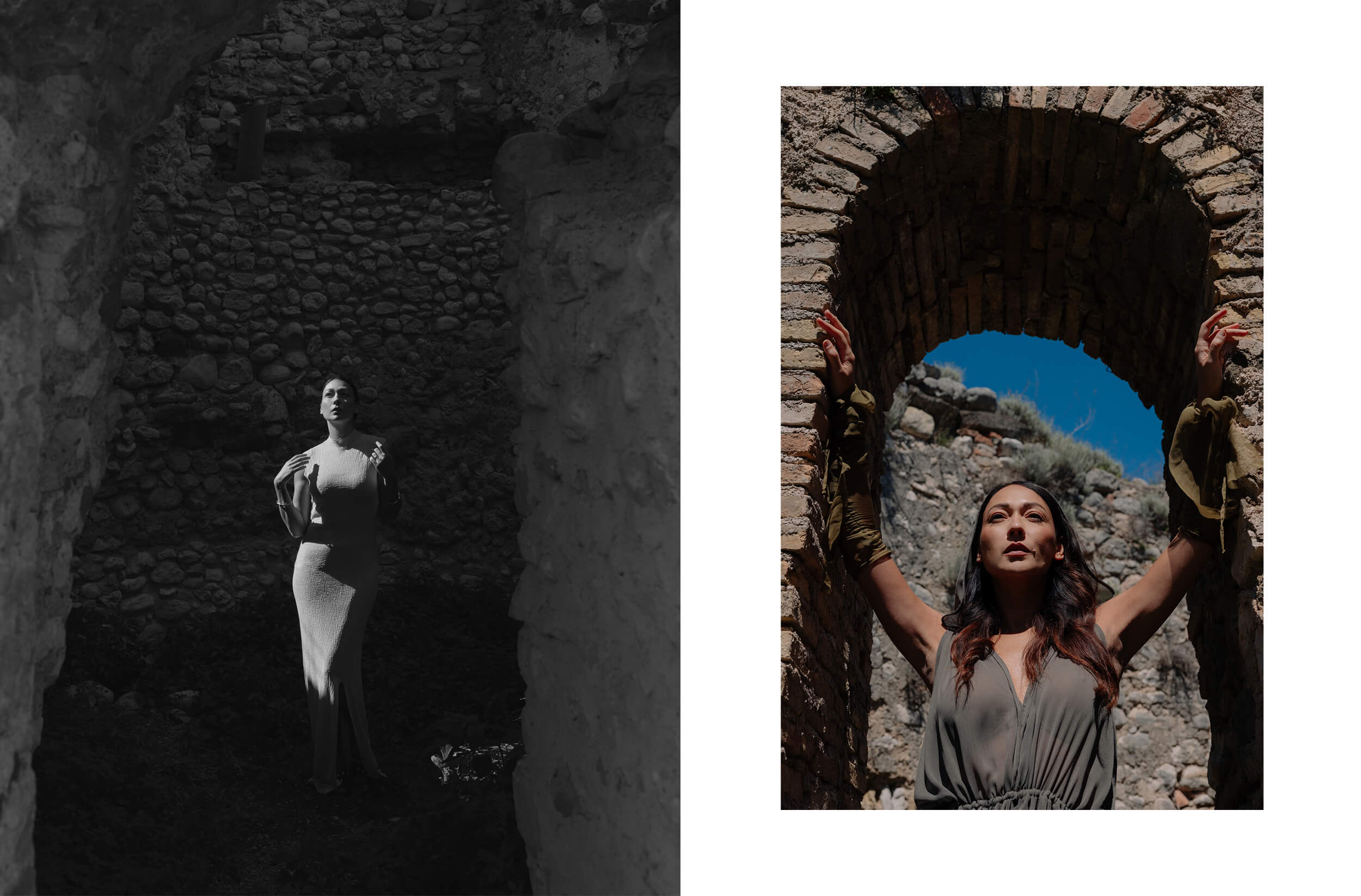

Photos & Video by Johnny Carrano.

Makeup and Hair by Micaela Ingrassia.

Styling by Sara Castelli Gattinara.

Assistant stylist Ginevra Cipolloni.

Thanks to Other srl.

LOOK 1

Dress and Gloves: Palmatic Studio

Shoes: Sergio Rossi

LOOK 2

Dress: Max Mara

Ring: Federica Tosi

Shoes: Gianvito Rossi

LOOK 3

Sweater: Alessandro Vigilante

Skirt: The Frankie Shop

Shoes: Sergio Rossi

LOOK 4

Dress: Calvin Klein

Bracelets: Argentoblu

Shoes: A.Bocca