There are books, TV series, stories that are much more than that.

They really speak to you, not as a reader or viewer, but as a human being: they reveal things, about who you are, that you are almost afraid to realize how true they are, how much they are part of you. This epiphany, this poignant journey through my person and personality, took place with “Everything calls for salvation“, the beautiful novel by Daniele Mencarelli that won the Premio Strega Giovani 2020 and which was then adapted into an equally valid Netflix TV series (of which the second season has just been announced).

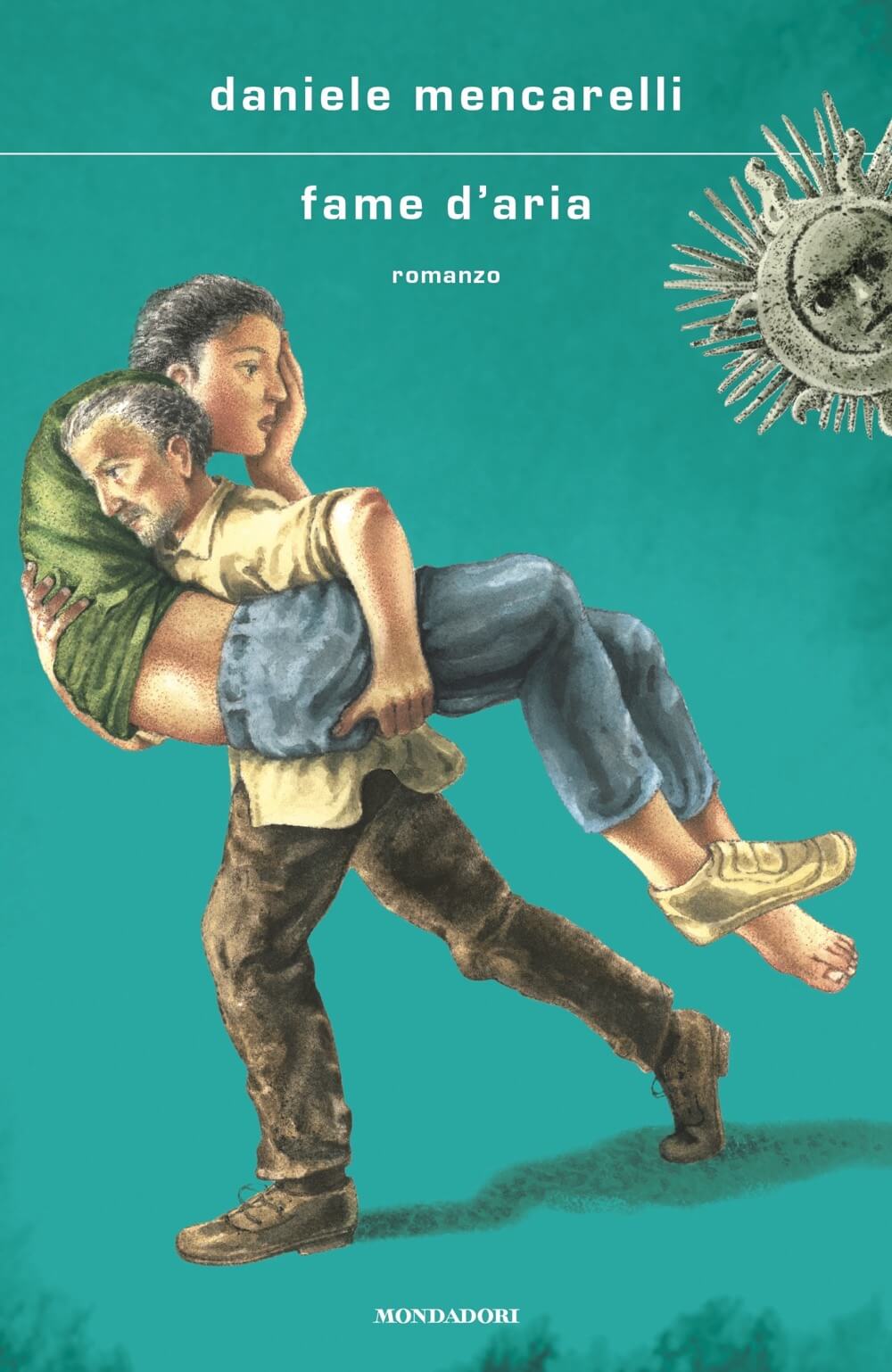

Later on, when I had “Fame d’aria“, Daniele’s latest novel, in my hands, I knew that, albeit in a different way, it would have been another exciting journey through what makes us human, or what we lack to be truly so.

And what a journey it has been: through the gestures of Peter, the eyes of Jacopo, the outstretched hands of the inhabitants of Sant’Anna del Sannio, we discover again, with more force, the most visceral emotion of all; that of the family, of the fathers and mothers who fight every day for their children and of the children themselves, who know how to give so much to parents, every day. All this facing the theme of autism, the feelings it brings with it, and the total indifference of the Italian institutions towards those in need, every day.

Later on, when I had the opportunity to talk with Daniele on the phone about this novel, his life experience, as a poet and writer, and how “existing” and “existing as human beings“, being able to listen, to support each other, to meet with each other and get excited are concepts inextricably linked to each other, I realized, once again, that salvation is not an idea, it is not a destination: it is a person. We all ask for things, but even more, we are salvation.

In “Everything Calls for Salvation” we can read: “Salvation. For me. For my mother on the other side of the landline. For all sons and daughters and for all mothers. And fathers” and in “Fame d’Aria”, the protagonist is actually a father: how would you describe the quest for salvation that Pietro carries on, more or less consciously?

Pietro is a man who perhaps doesn’t want any more salvation, he’s a man who’s searched for salvation through a miracle which then did not happen, and today he serves to the present only a huge anger for what didn’t happen, for what his son is and he can’t accept. He’s a man who’s being reintroduced to salvation thanks to the compassion of these three characters from this little town, they will reintroduce him to possible salvation by obviously and finally going through the processing of what happened and what his son is and will forever be because autism, differently from illnesses, doesn’t involve any healing dynamics. Autistic kids, boys, and men can improve with therapies, but autism keeps being a pervasive disease that sticks with you all lifelong.

For Pietro, salvation certainly goes through the acceptance of his son.

While reading the title, I thought about how sometimes we use the expression “love thirst” and, through the novel, Pietro shows us the consequences and the characteristics of his “unlove”. I firmly believe that both the presence and the absence of love (in whatever declination) have consequences on our life: how do you face your “unlove” moments? On the other end, when has love represented your “safe space”?

In human beings, especially when we talk about consanguineous love, there’s this weird detachment between what we say and what we do, and deep down this is what Pietro goes through, as well. He’s a man who with his words, but also with his actions, gives proof of detachment, unlove, tiredness, and anger. Verbally, he’s very sharp in showing all this, but in action, he never stops being the only support for his son. Often, in our relationships, we are that very detachment, we are something that in words says and states tiredness, if not unlove, and then, though, keep on practicing love. I can find this in Pietro, but I can also find it if I think about my childhood with my parents, and myself as a parent: oftentimes, we express tiredness but then somehow stay faithful to our roles. Maybe, being able to talk about tiredness and taking it out through outbursts of feelings is the only way we have to keep doing what we’re designed to do, both as parents or sons and daughters. At some point, in fact, sons and daughters become parents of their own parents in this game that’s the game of existence.

Where do the characters of this ensemble work originate? How did you shape them and give them a voice?

The theme of autism comes from a personal experience. My son has had a positive journey, benign compared to autism, but over the past 12 or 13 years, my wife and I have been around lots of neuropsychiatry places in Italy. Pietro comes from an encounter that put me in touch with a man who, exactly like Pietro, was experiencing that unmentionable tiredness, which truly seems to be leaving no way out. The small town, instead, comes from yet another experience. A long time ago, when I was a boy, I worked in Molise, and these tiny towns which were risking depopulation already many years ago remained in my heart. I always say that writers are serial accumulators, they keep everything because that very everything will eventually turn out to be what they needed, the reason why perhaps they’ve remembered it, the reason why it stayed in their mind, in the end, reveals to them and maybe goes into a story.

“Maybe, being able to talk about tiredness and taking it out through outbursts of feelings is the only way we have to keep doing what we’re designed to do, both as parents or sons and daughters. At some point, in fact, sons and daughters become parents of their own parents in this game that’s the game of existence.”

Pietro is in that grey area, that land of nobody located between “humanity” and “heroism”, between “compassion” and “courage”, where even morality doesn’t follow the same social conventions. Where is the limit between these two elements, in your opinion?

World Autism Awareness Day has recently been celebrated: I met an association in Minturno, a town on the border between Lazio and Campania, and we discussed these very themes. A parent should be a hero, in the sense that these categories are often used in bad faith by who, and I’m specifically talking about institutions, don’t do all that they’re supposed to do. On the contrary, parents, like all human beings, have resources, even love. However, if no one ever supports those parents in that relationship that’s so hard for a thousand reasons, starting from health problems and financial support, if no one ever helps and then hides behind these labels, “heroes”, “warriors”… But there’s no hero, there’s no warrior, there only are families living abandoned by the state. So, I always bring everything back to the human side: clearly, if we’re to judge Pietro and start from a moral judgment, Pietro is widely revisable, but Pietro’s story doesn’t require moral judgment, it requires compassion, it requires sharing within a hard faith like that of who has to take care of a severely autistic son who can’t make it alone. Otherwise, it all becomes too reliant on these supposed heroisms that are actually a litmus test for those who do nothing but hide behind these pretty words.

This is the message that stayed with me the most. Yours is a book that talks about communication, as well, on more levels: what Pietro holds inside, and then excessively vents, what Jacopo tries to express in his own way, what Agata and Gaia try to carry on… In a world that seems deaf when it comes to those who are left alone facing a situation like the one described in ”Fame d’amore”, what can each of us do, especially those who have the power, to give everyone a space to be heard?

This is a huge problem, in the sense that here two factors need to meet: on one hand, humanity as such, in its ability to rediscover itself as a community and as a network, and this is a job that concerns everyone. On the other hand, there’s the necessity that institutions recognize, starting from the financial side, some money that today they don’t grant to all those who work in the field of child neuropsychiatry. Unfortunately, in Italy, there’s a huge national emergency in terms of the lack of funds for all those places that should support those who are going through some hard times as a parent and as a person.

I guess that every book, with its research, writing, publication, and reception process, has an impact both on the life of who writes it and who reads it. What has “Fame d’aria” represented for you, and how has it changed you?

It changed me along with all that has come before the real experience, the testimonies from many parents, but also the past two months and a half since the book was published. If you will, people today are way angrier than people from 20 or 30 years ago, and this is quite interesting because usually the right to be angry is granted to young people; but I’m an adult and I’m very angry about all these faults of the State because so many families are really left in a condition of complete abandonment, so then we shouldn’t be surprised when we hear about terrible actions by people who take the life away from the children they brought into the world. Unfortunately, these are stories of abandonment, and Italy is a land of life and abandonment, so many different forms of abandonment.

“There’s no hero, there’s no warrior, there only are families living abandoned by the state. So, I always bring everything back to the human side.”

Also about this idea of the role of those who give birth and those who were given birth to, what message would you like the book to convey to the readers, especially to new generations, given that it’s Jacopo, the son, who saves the father, in the end?

I wish the book could give this idea, that parents, also those who don’t want to admit it, are fallible individuals who often need their sons and daughters to survive. The other idea, instead, according to which parents are always and anyways strong and enough for their fate, in my opinion, for the ideas I have as a parent, is not my educational proposal. I’d like to share with young generations the witness that parents, often, are so in love with their sons and daughters that they fall into an extremely deep crisis for whatever concerns their sons and daughters’ lives, when they go through hard times, not to mention illnesses. A man or a woman, the moment they become a father or a mother, puts the health, happiness, and well-being of their son or daughter ahead of theirs, and this is also to say how much a parent is often fragile in front of certain fates.

At some point, Gaia underlines the importance of “Finding the good in everything”: where have you found your latest “good thing”?

For me, these books have been a huge multiplier of encounters that, for me, are the great art of human life. The art of encountering, the possibility to share certain themes and experience them together: without encounters, humans become impoverished, and risk getting crazy, I believe.

Today, with the journey you’ve made, what does it mean to you to feel comfortable in your own skin?

It means embracing even my most painful and suffering part that continues, paradoxically, to be the most propulsive one when it comes to writing, the most interrogating one. It means to accept this part of me that continues to be viscerally attached to certain themes, to ask certain things, to propose certain quests. Today, I defend even that part of me that’s the most pain-provoking one in my life.

What book are you currently reading?

At the moment, I have lots of books on my nightstand because last week I was in Tuscany where they gifted me with so many beautiful ones. I’m reading a booklet from an author of Roman and Pisan origins, who starting from a Pasolini interview, tells the relationship between Pasolini and his mother. For me, it’s very nice because the poems about motherly figures are those who made me want to write poetry the most because that’s a reference figure for me, as well. This book tells how Pasolini, starting from his poems in dialect, has always found in his mother a big element of conjunction with the sacred.

“Without encounters, humans become impoverished, and risk getting crazy, I believe.”

Which untold story would you want to tell next?

My next book, which is partially already in my mind, will tell another theme that’s very close to me, a sort of more archetypical theme, that is the relationship between individuals and their origins. By “origins” I mean family, socio-cultural habitat, and everything we consider our origin.

“Everything Calls for Salvation” part 2: what can you tell us about it?

It’s interesting because the series, as it is set in present times compared to the novel, will enter a full fantasy dimension where Daniele will keep being the same Daniele from the novel and the first season, so a boy struggling between feelings and feeling too much. He will stay the same protagonist dealing with new events that will put him to test.

One curiosity: how does it personally make you feel to go back to this story after so many years, with the time adaptation, as it’s going to be a new form of writing compared to the novel on which the first chapter is based? How are you feeling right now, with this perspective ahead of you?

I’m living this with feeling the strong responsibility to represent the world of psychiatric disease. As of now, it’s not my story anymore, but rather simply, or tragically, the will to represent those that today are struggling with psychic or psychiatric disorders, and shape a narration that feels as faithful and true as possible to the people who are actually experiencing these things. Beyond my story, there’s a huge respect towards these themes that need to be told, a bit like autism, with great attention and respect.

Thanks to Mondadori