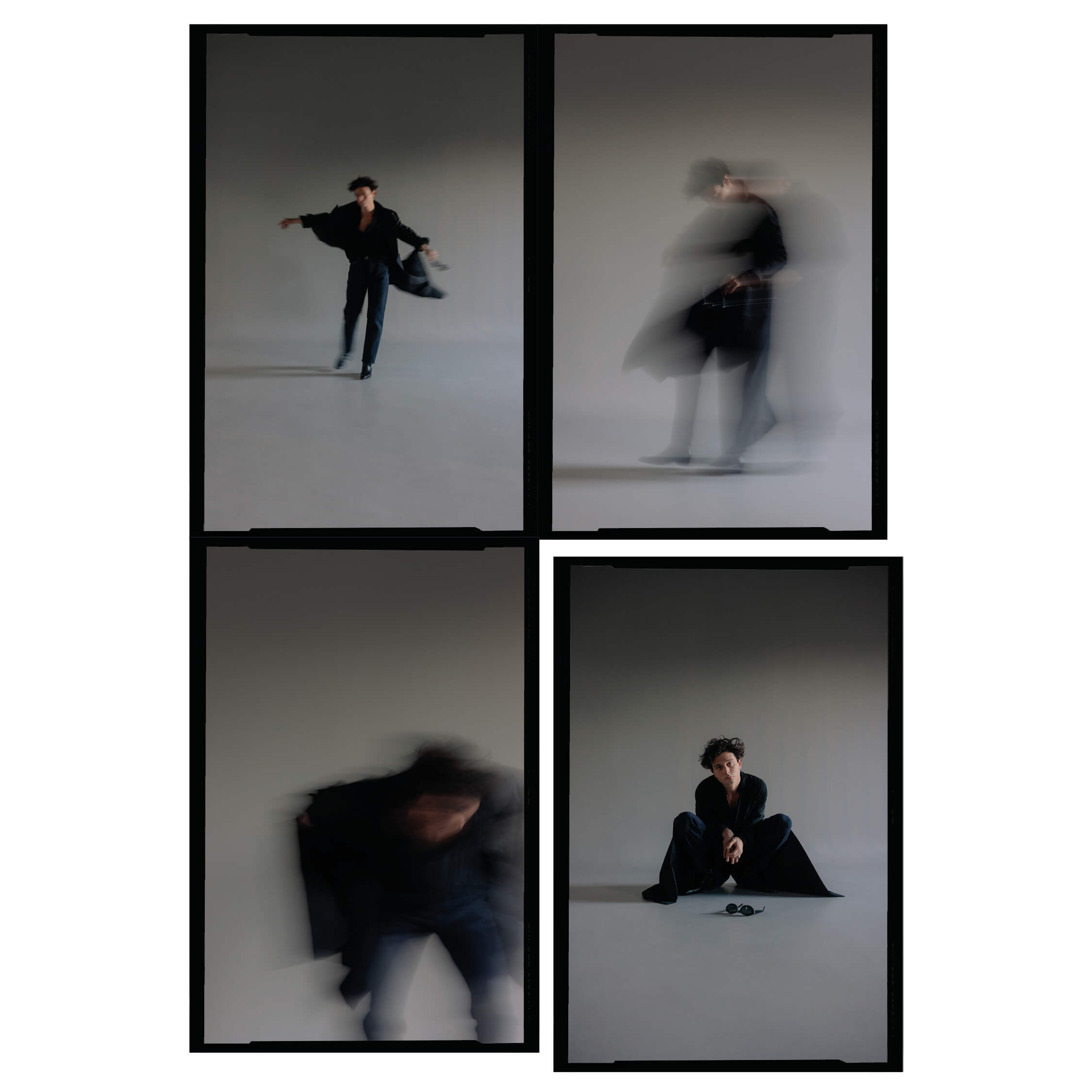

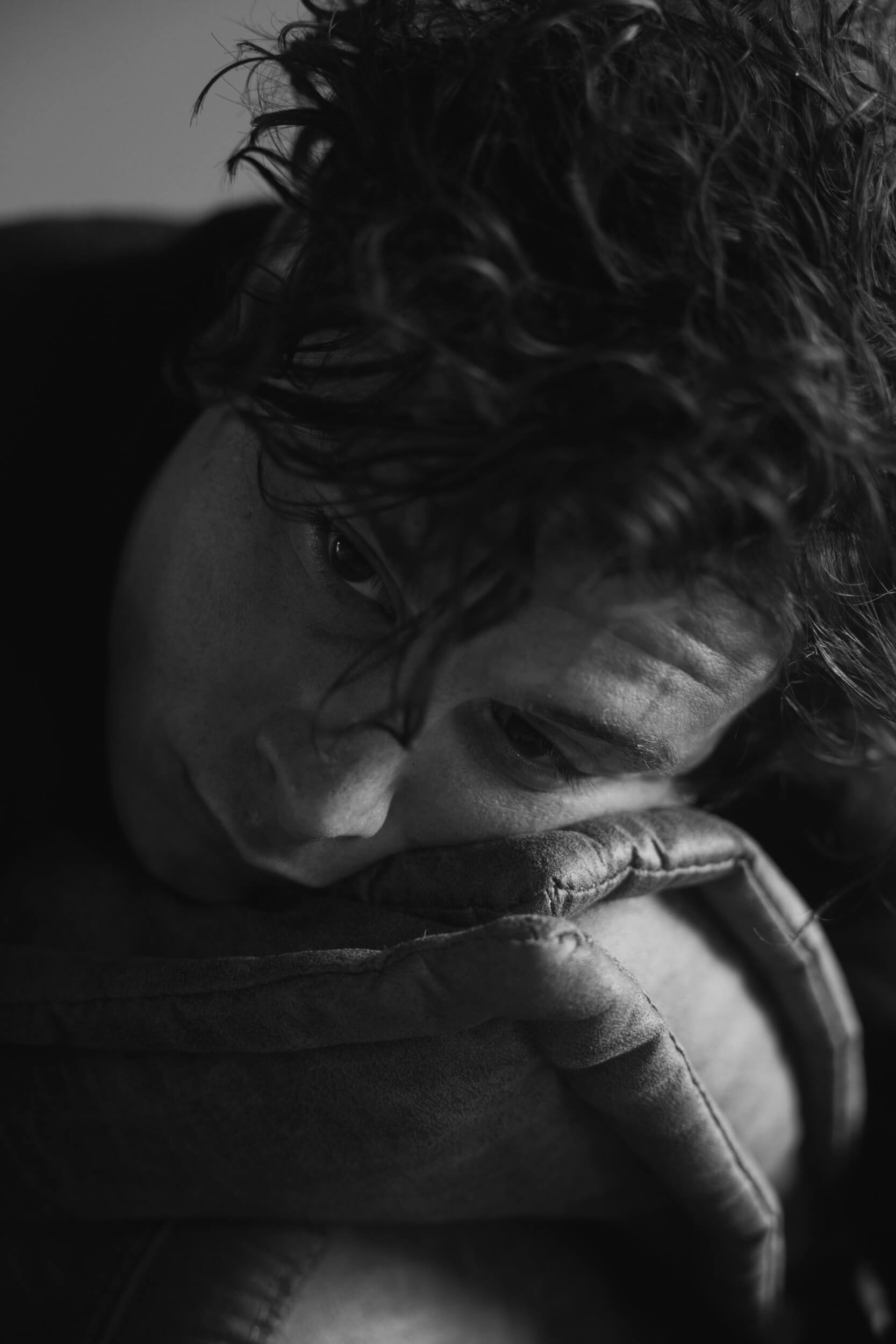

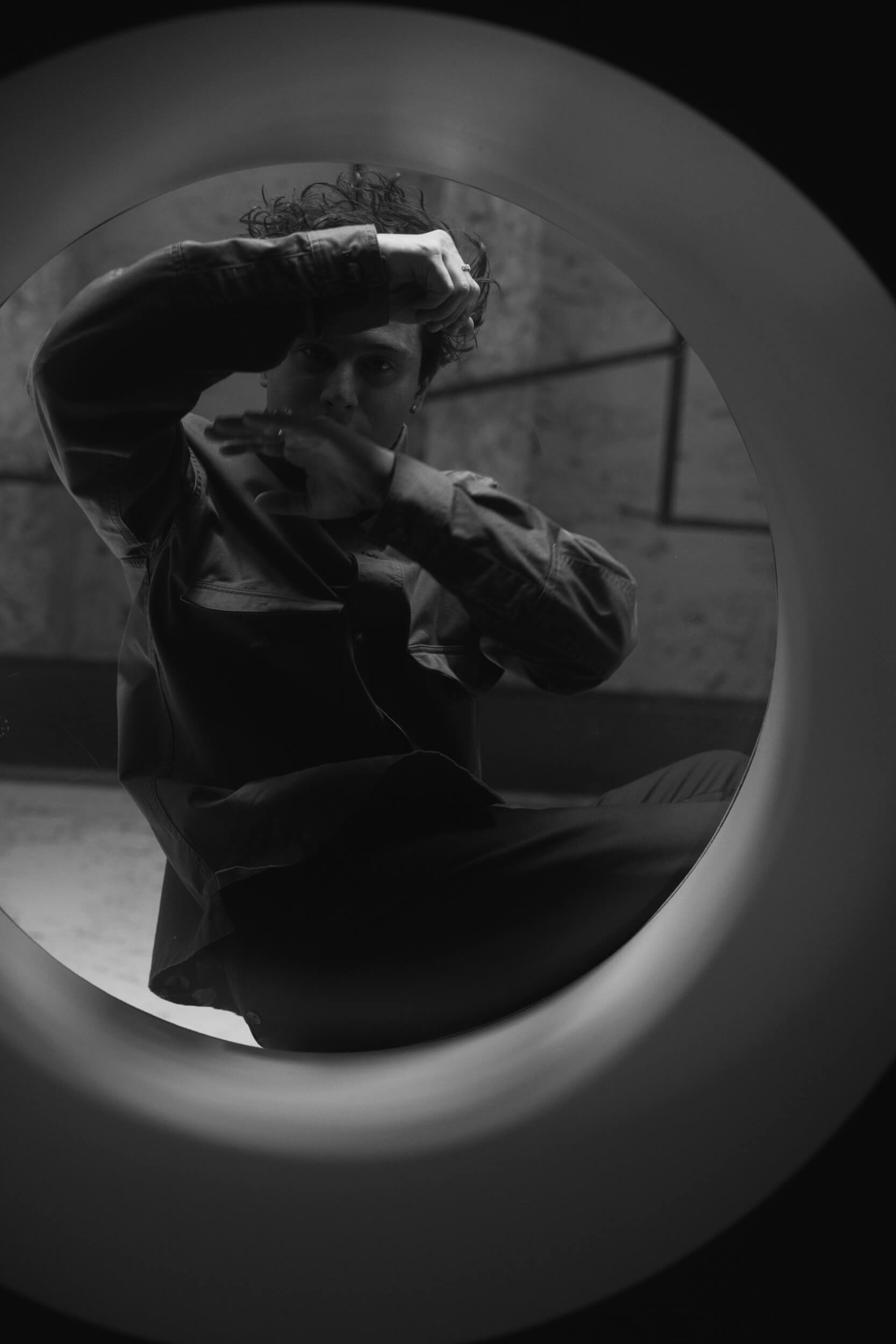

Exiting reality without losing connection with yourself: Daniele Rienzo transforms acting and music into vehicles that help him question himself and, consequently, grow. Through that blindness in the creative act that allows him to be truly and exclusively focused on what he is doing, Daniele has explored Raimondo’s fragility in “Parthenope”, reminding himself—and us—of the importance of heartfelt choices that can grow and lead us to greatness, as if they were seeds. Moreover, he embodies the strength needed to stay in the present, the beauty of generosity, and the ability to see oneself reflected in others through music. Daniele represents an incredibly human and nuanced poetic and communicative force, ready to be discovered through his means of expression. And this, is just the beginning…

What is your first cinema memory?

My first memory is in Sabaudia, when I had just turned 18. They were filming a movie—I don’t remember the title—in which I was an extra. There was this scene on the beach with Alessandro Gassman and other actors at dinner together, and something magical happened. In that moment, I decided I wanted to do this job. I remember a precise moment when the actors were joking like friends, but when the director called “action,” it was as if they all fell silent and entered a magical bubble to start filming the scene. I thought, “How did they step out of reality like that? I want to do this, something that allows me to totally escape reality whenever I want.”

Do you still manage to find that magic today?

Yes. Music helps me a lot with that now, too. In music, you have to find a certain magic, solitude, and a bubble to express yourself and connect with what you’re doing.

I always say that to do anything well, in any job, you have to be blind: when you reach a kind of blindness in the creative act, it means you’re truly connected, like activating an autopilot guiding you to make the right choices.

“I always say that to do anything well, in any job, you have to be blind: when you reach a kind of blindness in the creative act, it means you’re truly connected”

As if you detach from yourself but simultaneously internalize yourself?

Yes, in that moment, you’re connected with yourself on a higher level.

I have a friend who is a high-level boxer and also owns a restaurant. During a time when he was unsure about his direction, I told him, “You should do what makes you blind. What makes you blind when you do it?” He replied, “Fighting.” And I said, “Then that’s what you should do in life. That’s your calling.”

It’s very simple to understand what you’re called to do. It’s also fair to have doubts about what you do—it’s very constructive. If you don’t question yourself, growth isn’t guaranteed.

In “Parthenope,” I had the impression that Raimondo and Parthenope, though siblings, are two sides of the same emotional coin. Your character seems to live “within” emotions, while Parthenope tries to fully experience them to make sense of them. How did you approach creating such a character?

It all started with Paolo Sorrentino’s incredibly talented and empathetic writing. Paolo writes beautifully—I love reading—and when I read the script for the first time, it felt like the seed of everything I needed to build the character was planted inside me. I owe so much to Paolo and the discussions we had about the fear of self-doubt. This allowed me to work with great dedication on the physicality, psychology, and habits of my character, who is very delicate and complex. I immersed myself in the daily routines and emotional states needed to embody that character, working on it for months.

I think you effectively conveyed the fragility or “different” strength that Raimondo possesses compared to Parthenope’s more dominant personality.

Thank you. I believe fragility and tenderness are revolutionary. We live in a world that teaches us to build shields and put aside our vulnerability and tears. But I think sensitivity and empathy are revolutionary, and every artist should confront them and have the courage to face themselves to create a revolution in a world that encourages the opposite.

For me, it was an honor to portray a character with such profound fragility.

“I believe fragility and tenderness are revolutionary.”

What would you say to Raimondo if you could?

I’d tell him to always follow his heart.

One of the film’s most beautiful lines is the question: “Do you love too much or too little?” How would you personally answer that?

I’ve never thought about it! [laughs]

I don’t think there’s a definitive answer. Sometimes we love too much, other times too little. But the truth is, love is simply about letting go. There’s no “too much” or “too little”—it’s about acceptance, sharing, and communication, whether in friendships, communities, or relationships.

“Sometimes we love too much, other times too little. But the truth is, love is simply about letting go”

The melancholy of youth seems to run through the story, connecting Raimondo, Parthenope, and Sandrino. What feelings would you associate with the past, present, and future?

Personally, I try to stay in the present as much as possible. That said, I aim to have as few feelings as possible about the future and the past, though it’s hard. I’m deeply attached to nostalgia, which I find revolutionary.

Gary Oldman said something in a press conference at Cannes: “People often take a step with one foot in the past and one in the future, and they piss on the present.” I found it to be a precise critique of societal pressures to constantly work, rush, and dismiss the value of the past and nostalgia as distractions from building the future. But in doing so, we forget the present—how we approach love, which should be rooted in the present and is inherently all-encompassing.

I read that Paolo Sorrentino taught you the importance of having the courage to be generous. How do you practice this in everyday life?

I’ve always been generous—I don’t believe much in private property. Everything I have, I share with my friends and family. My mother used to say, “Don’t give away everything you have!” [laughs].

There was a time when I overdid it and gave more than I could, leaving myself drained. That happened just before this film. Watching Paolo on set—remembering everyone’s names, knowing something about each of us, giving work to kids from the streets of Naples who wouldn’t have had opportunities otherwise—was inspiring. Seeing how generosity and empathy structured the set gave me hope.

It made me think it’s worth opening up, even if it sometimes hurts.

“it’s worth opening up, even if it sometimes hurts.”

You mentioned Naples, your hometown, and two of your latest projects, “Parthenope” and “Uonderbois,” which revolve around it. What is your relationship with Naples, and how has it evolved over time, also thanks to your work?

I spent almost ten years away from Naples, and I had friends from all over the world: Japan, Germany, England, France, America.

From an anthropological perspective, when you engage with such diverse cultures, you fragment and depersonalize yourself a bit.

Returning to Naples created a bond with my origins; it made me understand the significance of the phrase: “You can’t go anywhere if you don’t know where you come from.” When I came back to Naples, I felt a profound sense of understanding of the social fabric. It’s impossible to describe but entirely possible to grasp and feel.

My relationship with Naples is one of immense respect, especially artistically, because Naples is full of experimental realities, things I’ve only seen in England or Germany. Naples is special because there are people who create art without aiming for recognition and make experimental choices imbued with great courage. Naples inspires me, speaks to me, and makes me want to grow.

What about music? Can you tell us about your projects?

I have two musical projects: one called Bravodemian, inspired by Herman Hesse’s “Demian,” and another called F.M.C.P., which focuses on experimental music. During the Covid years, we performed in contemporary art galleries. Bravodemian blends genres, drawing from the ’60s—The Beatles, Pink Floyd, Joy Division—with New Wave, psychedelia, and experimentation.

Bravodemian includes songs in both Neapolitan and English, aiming to bring modernized “past” music abroad. We’ve even composed music for films, including Maria Tilli’s “Animali Randagi,” a wonderful experience.

As for future projects, after not performing for a year to work on “Parthenope”, we’ve just started again. We’re going on the radio, playing, writing, and trying to find the right balance in terms of poetics and communication. It’s a work in progress; we have a lot of material written that we need to release as soon as possible.

Cinema and music are channels for both communication and self-discovery. What’s the latest thing you’ve discovered about yourself through these two elements?

I’ve realized—more than discovered—that it’s essential to have a core group of people you love to truly be free in the creative process and act. It’s important to build a solid foundation of relationships, where you can see yourself reflected infinitely. It’s not about knowing many people; it’s about knowing the right people with whom you can have excellent communication, allowing you to understand and outline what’s happening in the world. Because each person is a mirror of everyone else, and this is a concept I’m trying to bring into focus with my film and my musical project.

“It’s important to establish solid relationships where you can reflect on and understand the world.”

A song that represents this moment in your life.

“Floe” by Philip Glass, from the album “Glassworks”.

What’s the last book you read?

I’m going through one of those periods where I buy and accumulate lots of books—I have them all piled up on my desk, and I’m reading a bit of everything in a fragmented way. The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber and David Wengrow; On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous by Ocean Vuong, a book of infinite contemporary power; to indulge my romantic side, which I can’t do without, Autonauts of the Cosmoroute by Carol Dunlop and Julio Cortázar, about the stage-by-stage journey the authors took in their Volkswagen van from Paris to Marseille, written the year before Carol’s death and a few years before Julio’s; and Siddhartha by Hermann Hesse, which I’ve never read and feel it’s finally time to pick up.

Your biggest act of rebellion so far?

I’d rather keep my acts of rebellion private—otherwise, they wouldn’t be as powerful. [laughs]

What does it mean to you to feel comfortable in your own skin?

I feel at ease with myself when I play music.

What’s your happy place?

My happy place is music.

Photos & video by Johnny Carrano.

Grooming by Sofia Caspani.

Styling by Sara Castelli Gattinara.

Assistant Styling Ginevra Cipolloni.

Thanks to Other Srl.

LOOK 1

Total Look: Saint Laurent

LOOK 2

Total Look: Pence

Shoes: Saint Laurent

LOOK 3

Pants: Uniqlo

Blouse: Saint Laurent

Shoes: Santoni