That “Mosquito State” had something unseen before we knew it from the very beginning and with the beginning, we mean the opening credits.

By the first minutes in, we knew it was going to be a film that would open a discussion, a film with different emotional responses – something that Filip Jan Rymsza, the director himself, hoped for. And we can definitely say that he achieved this goal.

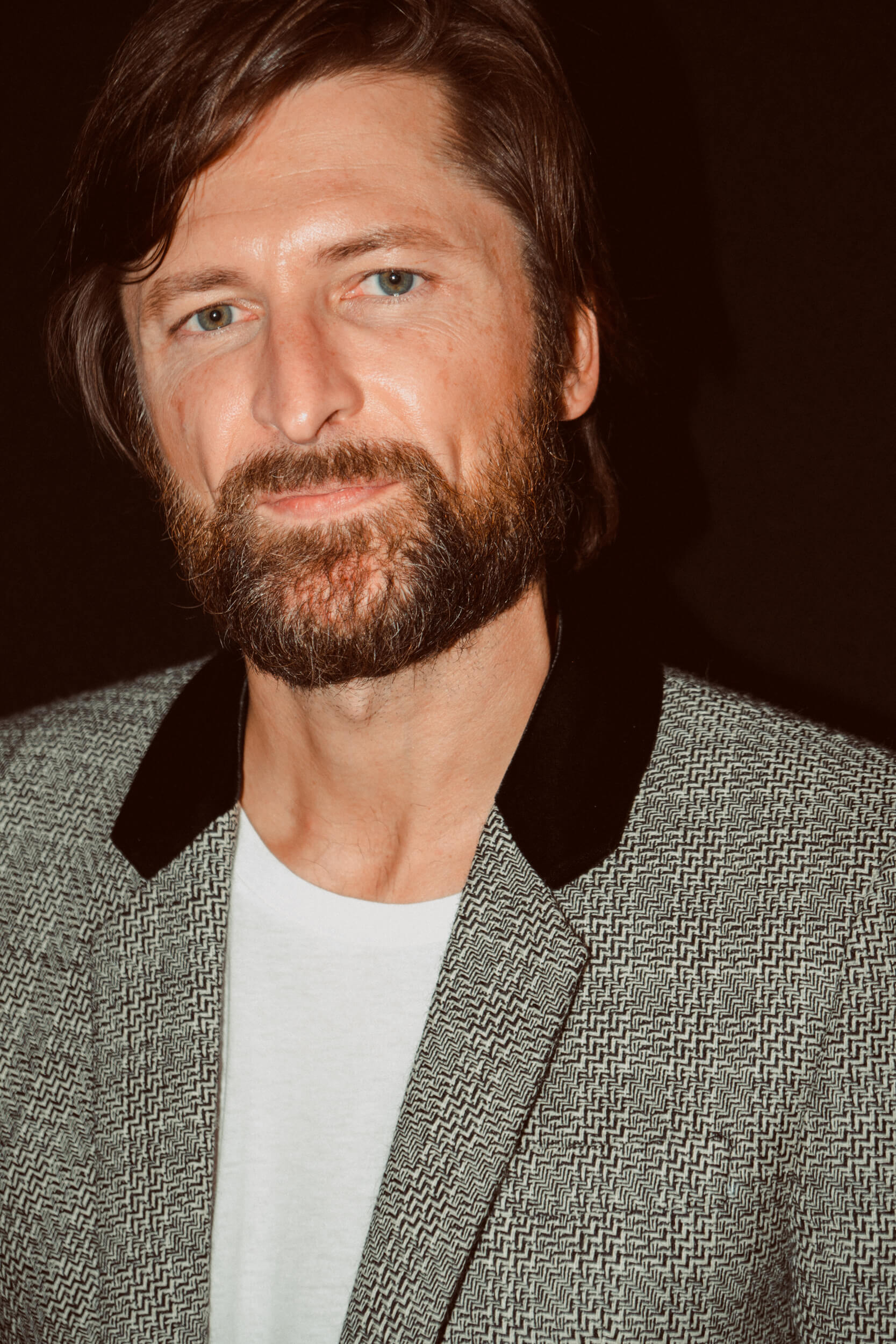

In our interview with him, we found out how this film came to be from a situation to a transformation…and much more.

What drove you to this film?

It didn’t start with the financial market and “Flash Boys” but it started with mosquitoes. I had a friend who had his apartment in LA infested with mosquitoes, so there was the idea, just an idea of something, I didn’t know, what the framework would be, when it would be set, how the story would eventually be told, and none of the narrative aspects, it was just situational: a man becomes obsessed with mosquitoes and then breeds them. That was my entry point.

How did you move on to quants and to Richard’s character, what was the process?

Who is that person? To be able to befriend a mosquito you probably can’t have too many options, so I think he’s somebody fairly antisocial. I thought about strict discipline, obsessives, and what kind of makeup does that person have. I started thinking mathematicians, but then it’s not something that was interesting enough and so I kept layering it, and then, of course, the book [“Flash Boys”], so I thought the golden goose: who is the golden goose programmer? Who does these algorithms for high-frequency trading? And this is how it started: “Okay, this is the guy,” and then 2007, with everything that was going on socio-politically and how it really spoke to where we are now. It just kept getting denser, so I kept layering and layering, knowing that I would eventually come back and have a character study, but everything else was already there.

“To be able to befriend a mosquito you probably can’t have too many options, so I think he’s somebody fairly antisocial.”

Did you meet real-life, Richard-like quants?

Not someone who exactly what he does. Not that it’s an interest of mine, but I studied economics and philosophy, so it’s a weird interception and a weird skill-set for a filmmaker, but I have a lot of friends who are similar to Richard, not in the antisocial sense, but who are in hedge funds, who have done some programming and they were a great resource for me. They could speak to this type of person, they could also help me with the jargon in the office, I would ask, “how would you refer to this?” and the algorithms that he rights are actual algorithms, they function, if somebody were to do it, it’s kind of similar to what he’s designed, so that level of detail was always very important to me. Of course, there’s going to be those 200 quants in the world who will watch the film and say, “no, no, no.” I don’t want to have a Reddit page with all the quants in the world telling me I did a terrible job. So, it’s a responsibility.

“The algorithms that he rights are actual algorithms, they function, if somebody were to do it, it’s kind of similar to what he’s designed, so that level of detail was always very important to me.”

What were the main challenges in bringing this project alive?

Firstly, for people to take a chance, either we talk about filmmaking, or how you find financing for a film like this. Then, from a casting standpoint, finding actors brave enough to take it on: because it could turn out to be a Venice premiere, or it could turn out to be a total disaster; the material is such that I could have taken it in so many different directions, and I knew I had something really interesting in my head, but the realization of it it’s not only from a production standpoint, and the scope and ambition of it were really big, and then it became the visual effects. Initially, I had one v-effects vendor and they said they would do the whole thing, but I ended up with 17, and I thought, “Maybe post-production… 6 months?” It took 19 months.

I partially did it in Warsaw, in Poland, but most of the production was on stage. And it was great because totally by coincidence I was working at another movie in Poland and then I spent some time in Warsaw and through that experience, a lot of people took interest in me and asked me, “What are you working on next?” I called them about this and I said, “I had this New York set script, I was thinking about shooting it on stage, maybe in Vancouver” and they said, “Why Vancouver? Why not here?” So, the conversation started in an organic way and they really liked it. A lot of things still had to happen, but they said, “Okay, come shoot at our stages,” and this was WFDiF, a 70-year-old Polish studio, and then the Polish Film Institute backed it, which again was risky for everybody, because “is it a Polish film?” I’m Polish, or dubiously Polish, because a lot of Polish people say, “You’re American,” so it’s an interesting conversation of authorship.

“…the material is such that I could have taken it in so many different directions, and I knew I had something really interesting in my head…”

Music and space, or rather emptiness, in the film, feel like two additional characters. Was this already in your mind while you were writing the script?

Sound design yes, for sure; score I wasn’t sure where I was going to go with it. Space, Central Park, the vastness of that, of the penthouse, the emptiness of the corridors, everything was in the script, or if not in the script, in my head. Sometimes, when you write for yourself to direct, you don’t have to put every detail. The script was 60 pages long, so a lot of it was simply me knowing what I was going to do, how I was going to shape it: I knew every single sky color, I knew every single important props because by reducing color or keeping things monochromatic you can draw attention to things, so it was a very carefully crafted film. Depending on how much people got into it, you want to give them more and more layers so that the film really holds up, it’s something you want to watch three or four times, they’re going to continue finding things in there.

“Space, Central Park, the vastness of that, of the penthouse, the emptiness of the corridors, everything was in the script, or if not in the script, in my head.”

How did you work with Beau especially on the arch of his character and on his physicality?

Beau is not Richard by nature. He’s so muscular, and it was very difficult for me to envision him initially. He’s just so passionate about it, he fought for this role. And you want that, you want somebody who feels that and in a way, we’re gambling on each other, because he doesn’t know what’s in my head and as much as I can tell him you don’t know what the end results are going to be. With him, it started with his physical transformation and he brought a lot of that to it. Anybody can lose weight, but to me the real challenge is in him changing his posture, his movement, being vulnerable, being insecure, showing that side of himself, that he really was scared, and that’s good, I was like, “Yes, go there because this is a real performance and you’re giving me something.” It’s such a brave decision and he made some really bold choices. I’m very proud of him.

“…the real challenge is in him changing his posture, his movement, being vulnerable, being insecure, showing that side of himself, that he really was scared…”

How do you feel about this movie?

How do I feel? I’m very proud of it. I know it’s something super cool, I hope people respond to it, maybe it will be one of those films with a very wide spectrum of emotional responses.

The most important thing is that I want to foster thought.

Photos by Johnny Carrano.