A raw, realistic, intense, touching, sensitive documentary, and the list of adjectives could go on and on.

With “Life of Crime 1984-2020,” director Jon Alpert does it again. Through the lives of Rob, Freddie and Deliris, he shows us how difficult life can be for those who might be living next door, how our priorities as a society might be misplaced and and how this can lead us to the wrong path.

We are not born criminals but we might be raised into a life of crime when left alone especially by a system that keeps turning its back to those who might be in trouble but that are and should not be out of hope.

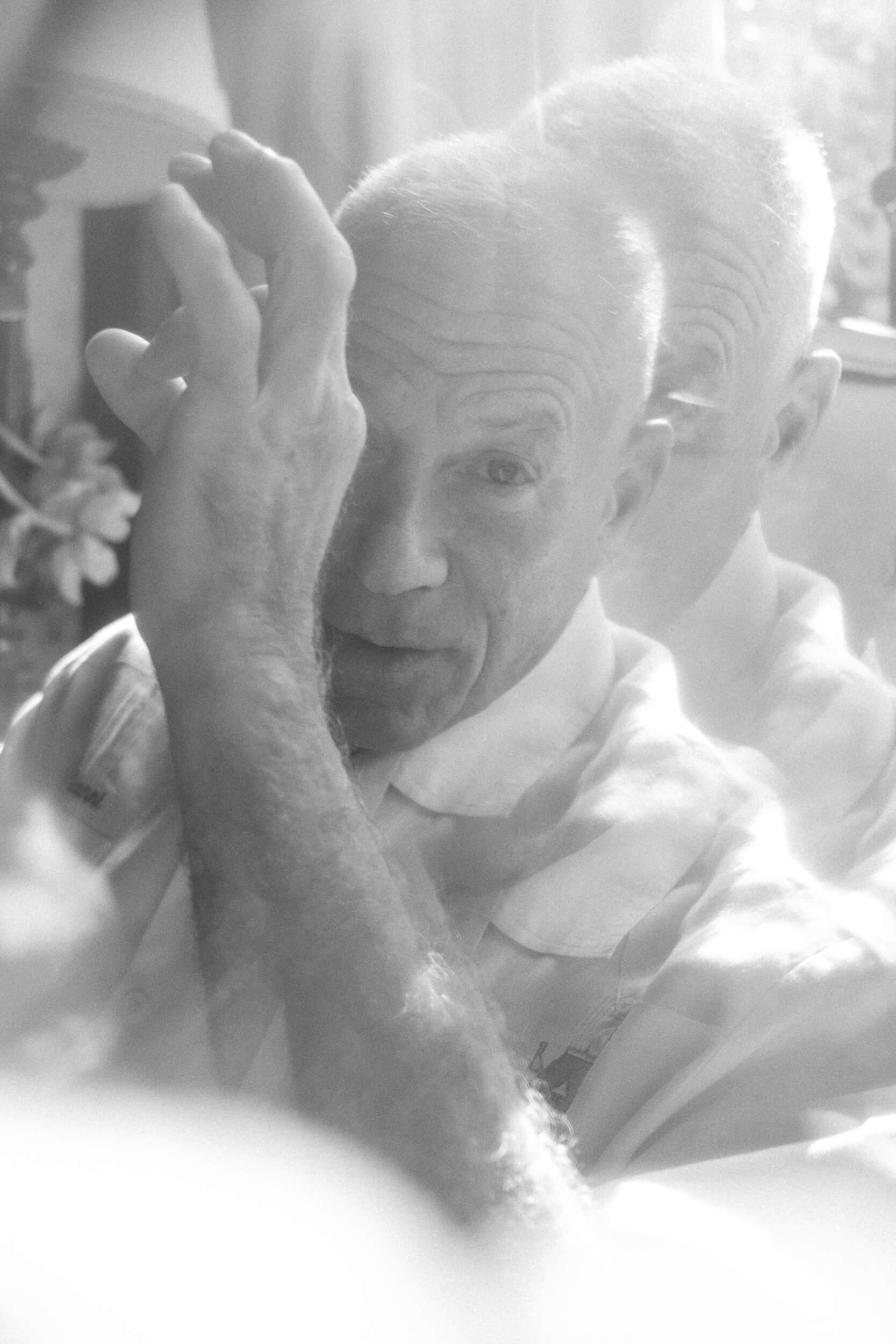

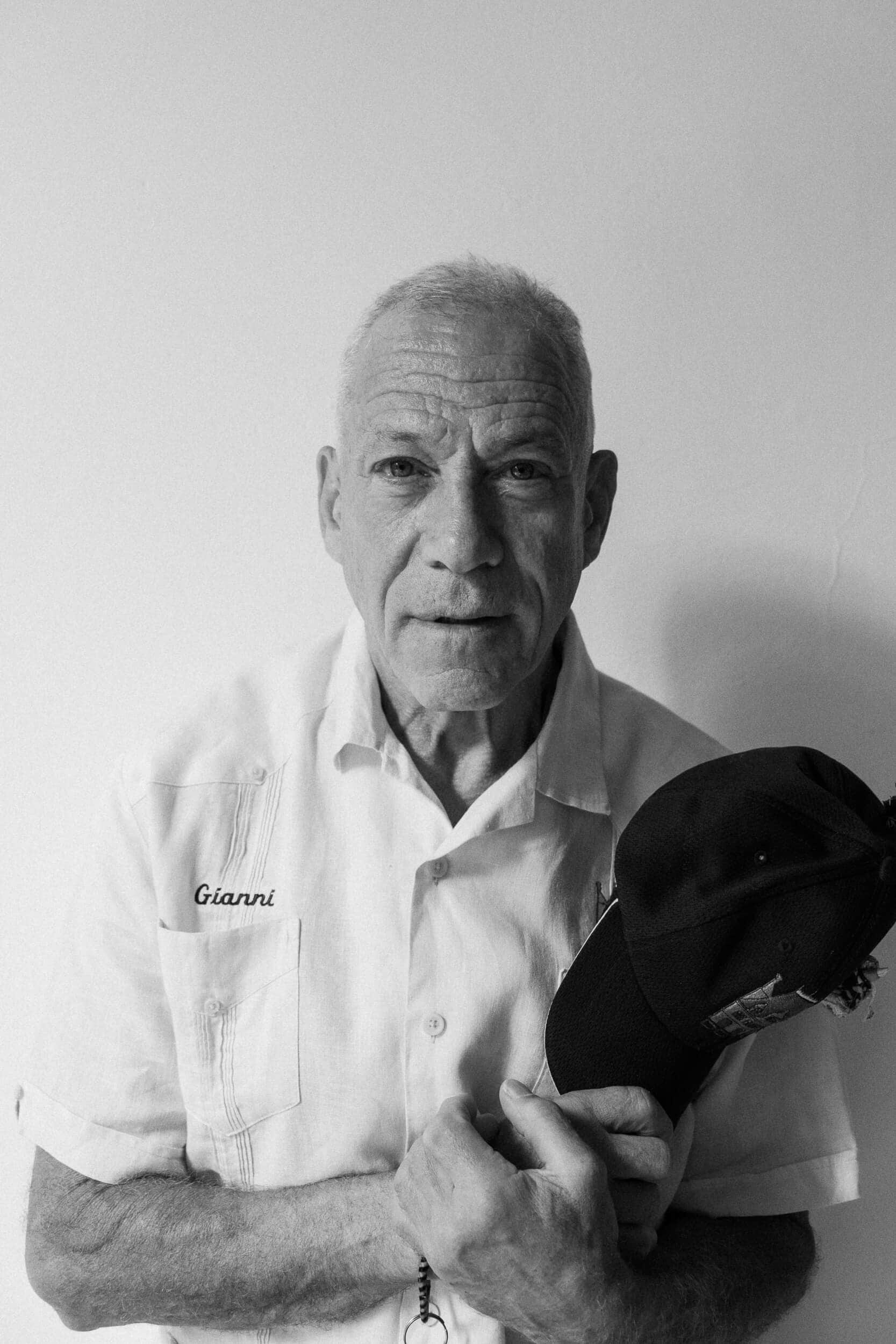

Here is our interview with Jon on the incredible journey that was making this film.

I watched the documentary last night. It was intense, I’m still a bit shaken. I think you’re able to portray stories in a way that really stays with you and makes you think. How did it all start? Where and how did you meet Freddie, Rob e Deliris?

When we started this project, we’d never thought it was going to be anything like this. Initially, we were victims of crime, my motorcycle was stolen two times in one week, other people had their apartments broken in and so on. Who was doing this? Because we have been brought up with the idea of going to the store and paying, and not stealing, so I wanted to try to understand what was going on in the heads of people who were basically full-time criminals.

We were introduced to Rob, Freddie and Deliris, and I asked if I could follow them, and at first, I had no idea where it was going to end, it was like grappling onto the tail of a tiger and holding on for dear life. I was quite fascinated with how smart they were, and with the general exception of Mike, how nice they were, and how different they were, the way people who didn’t commit crimes were, and how really good they were at their crimes. I didn’t know, in the beginning, that they were addicted to drugs, and I didn’t understand how drugs would wind up taking over their lives and taking over the whole community. This was supposed to be a short news report, but it turned into 36 years.

When did you realize it was going to be that long? Was there a moment where you said, “Okay, maybe this is going to take me a longer than I expected”?

It was a number of things. First of all, the violent nature of some of the activities that we had not expected, the fact that I didn’t think we could properly tell a useful story in a short period of time, so we began letting time become a factor in telling the story. But sometimes, you need to let time show you things and teach you things.

Was it easy to get involved with them? Were they open to do this when you approached them?

I think surprisingly so. I think that I showed respect for them as people, I showed respect for their craft and ingenuity; and they also say this in the film, by this point, they had realized that much of their life had become destructive, self-destructive, destructive to their families, destructive to their community. By having other people see this, they felt that they were now doing something with a positive value. I believe that, too, that’s why we made the film. They believed this, and you can see what they shared with the camera, and basically with the public was extraordinary.

“…sometimes, you need to let time show you things and teach you things.”

“…they felt that they were now doing something with a positive value.”

You can also see the friendship between you that came out of this. Between filming, were you in touch with them? When did you decide to go back to filming? I imagine there was much more footage than what we see.

This film is from HBO, so one of the interesting things is that HBO lets you spend as much time in the “kitchen” as you need to, that’s always been one of the most supportive things they do for the filmmakers they work with. Right from the beginning, they were interested in telling the story and allowed us to work on it for almost 40 years, so HBO was onboard from the beginning, differently from “Cuba and the Cameraman.” This is one reason why almost everything I’ve ever done has been done with HBO.

Also, my daughter grew up helping me filming, she knows everybody in this film from the time she started working with me on this, which was when she was 9 years old, so she grew up within this particular project with the families that are in the film, you don’t see the outtakes, but she’s in all of them, so this is an unusual mixing of families. When it was birthdays, sometimes I’ve missed family birthdays, but I’ve never missed the birthdays of Rob, Freddie and Deliris, and their kids, so that’s another important aspect of this. What you don’t see is that for every crime I’ve filmed, there are ten times I took them to rehab and tried to get them to do the right thing. We didn’t encourage them to do anything bad, they did bad things out of necessity and sometimes out of desperation, but we always encouraged them to do the right thing, and any time they wanted to, as it’s pretty hard to get rehab in the United States, especially if you’re poor, we would drive them, and if the rehab would tread them away, I would call the rehab and threaten them. Naomi [Mizoguchi] is the assistant editor, so she was responsible for hundreds of hundreds of tapes in a dozen different formats, and trying to figure out how to make that stuff all talk to each other. The challenge was to tell this in two hours, I don’t know if we did the best job, but at one point I tried to talk HBO into doing a 5/6-parts series because we had so much material, but they wanted something cinematic, so this is what we did.

Were you editing as you were filming?

Yeah, all the time. HBO has broadcast two earlier documentaries, one filmed the very first year in which we were very primitive filmmakers, and it’s energetic, I’m not sure it’s great filmmaking. It’s quite legendary in filmmaking because when we filmed this, and all these things were happening on camera, I don’t think anybody had ever done it before; now, it’s been 40 years, so I think all these things have been represented by other people, but as we were doing this, we were probably the first people.

“What you don’t see is that for every crime I’ve filmed, there are ten times I took them to rehab and tried to get them to do the right thing.”

You mentioned you were also trying to help them, and never encourage them, but was there ever a moment in the film where you thought, “This is too much to film, to see,” from an emotional point of view?

From an emotional point of view, Rob, Freddie and Deliris’s deaths were hard, and Deliris’s was the one that was most unexpected. If I would have known that this would be the ending that real-life gave to us, I don’t know whether I would have continued this to the end. It was heart-breaking, it was not the story that I thought I was going to tell because when Deliris came back from the dead the first time, and she rehabilitated herself and became a really important force in the community. I had stopped filming and gotten depressed by the story and didn’t want to work on it anymore; and one day, Deliris calls – and everybody thought she was dead, and you see that last time I’d seen her in the hotel she weighed 60 pounds, and nobody thought she would survive – and she says, “Hi Jon, this is Deliris,” and I say, “Who’s this? You’re tricking me, please don’t play games, Deliris is my friend,” and she says, “No, Jon, it’s Deliris,” and I say, “Oh! You are Deliris, and you’re not dead!”. She said, “Not only am I not dead, but I’ve also been drug-free for 40 years, 3 months and 7 days, and I want you to come with the camera because I want people to see this, this is the story that I want to tell and I was able to overcome this.” And she did, until the pandemic; she was very good, she went to meetings every day, she had a psychiatrist, she had a group psychiatrist, but all that stuff disappeared in the pandemic, and basically, we abandoned her in terms of the services. I would talk to her once a week, she had gotten engaged, she was going to get married. She went to the beach, in the middle of the pandemic, she came home, then I called her on Sunday and she didn’t answer, I called on Monday and she didn’t answer, and I found her dead on the floor. No fun. But I think you can see her bravery, Rob and Freddie’s bravery to be able to tell their story.

“It was heart-breaking, it was not the story that I thought I was going to tell…”

When we see Freddie and Rob’s death, you are heartbroken, but then you see Deliris, you feel there is still hope. We’re not made to be alone, as human beings, we have support systems, our families, our friends, and also the Country we live in should be part of this support system, and I thought that this would have been a lovely end for the movie, but then you see Covid coming and shutting everything down, and Deliris ending up like that was a punch in the gut, I wasn’t expecting that. I imagine how heartbroken you must have been. When we see her getting the awards for all the things she did for the community, I thought that that was going to be the end of the movie…

Actually, we had a bigger end. The mayor was going to have “Deliris day” and he was going to give her the key to the city and have a parade through the neighborhood; that was the ending of the film, but we never got to it, and it’s too bad because the mayor understood that she was a real hero, and we all wanted to inspire everybody in the community. I think we were successful in showing what real life is, but we weren’t successful in having a real-life with a happy ending.

“I think we were successful in showing what real life is, but we weren’t successful in having a real-life with a happy ending.”

You did this documentary over a span of more than 40 years, do you see a change in the support system, also Government-wise in the US?

No, it’s worse. There have been cutbacks again. We invest in strange things in the United States and it’s getting stranger and stranger, and I think there was a time many generations ago when the goal was “invest in infrastructure and build the country; invest in schools and build the people” but we are not doing that, we are just fighting each other right now. And if we are preoccupied with this fight and with these crazy divisions within our Country, we will be never able to focus the energy and resources we need in order to fix this; and we’ll slide through this for another couple of generations because the Country overall is very wealthy, so we have this residual wealth, we’ve exploited everybody around the world for hundreds of years and sucked everything into the United States and that stuff is getting sucked out, resources are getting concentrated in very few hands…and it doesn’t look good.

What would you like to see change-wise in the next 10 to 20 years?

There are good people in large numbers in the United States who are trying to do the right thing; we really have to invest money in our schools and not in our jails, we need to invest money in different types of drug treatments and especially helping people get any type of job that gives them pride and structure in their life. When Rob, Freddie and Deliris had jobs, they were fine and the day they lost their job…the clock was ticking to a bad end. I understand that the Country can’t invest in everything that we need, that’s not realistic but if we change our priorities a little bit, it would be good. Rob, Freddie and Deliris were very smart people with a tremendous amount of potential, and if they could have put all their creativity into something that was a little bit more positive and less destructive it would have been great for them and great for us.

One of the reasons why I know that investment in the early stages of life is useful is as we do this in our centers, so we have had since 1978 a program to teach young people how to make films, and even during the pandemic we figured out how to do this remotely and we had 5 of our students make films about their lives under COVID. These are kids from poor families, doing also dangerous job, and they had mothers and fathers with COVID coughing in the other room, can you imagine that? Thinking your father or mother is dying from COVID in the next room. And they made movies about this. They were very brave. So HBO broadcast that, it was the first time, high school kids had anything broadcast in a major channel.

100% of our kids go to college and they all come from families similar to Rob, Doloris and Freddie’s. And with opportunity, good things happen. So I know this works.

“We need to invest money in different types of drug treatments and especially helping people get any type of job that gives them pride and structure in their life.”

“100% of our kids go to college and they all come from families similar to Rob, Doloris and Freddie’s. And with opportunity, good things happen. So I know this works.”

So can I ask you a question instead? What did you think about the music?

When I first heard its allegro rhythm, it kind of made everything more real, you don’t need the music adding to the sadness you are watching, the images speak for themselves besides, as you said, Rob, Freddie and Deliris are smart people, they are human, and the music adds another layer to that.

You see, you are the first person that I’ve talked about the film to outside of my circle so this is why I’m asking this question. When making the film we used temp music, and if the scene was sad, the temp music was sad. I really respect the composer [Residente] and went after him to see if he could work on this film, he hadn’t worked on anybody’s movies before, he did 2 movies himself. In the music world he is a superstar, he has 4 Grammys and 27 Latin Grammy Awards—more than any other Latin artist, so he looked at the film and said, “yes, I would like to do this” and I was so happy, and then his music came back, it was unexpected, and when there was a sad scene, the music wasn’t necessarily sad and he said, “Jon, do you put salt on a pickle? Do you put sugar on top of ice cream? That’s not what the music needs, the music needs to add something else to the scene.” And as he began sending me music and adding this extra dimension, I really liked it. So I’m curious to hear how people react to it. It’s different from documentary music.

Last question, what can you unveil about your next project?

I’ve been working for the past 4 years on a very unusual climate change movie: I’m a very enthusiastic but not so good ice hockey player, I grew up playing hockey outdoors, and now you can’t play hockey outdoors where I grew up because it’s too warm, and it’s like this all over the world, and one of my friends is the most decorated hockey player in the world, he’s from Russia, he’s won 3 Stanley Cups, he’s won 5 Olympics Golds and so on, and he says the same thing, he grew up skating on the ponds. So we are making a film called “The Last Game:” we are playing hockey games on top of the Himalayas, where you don’t think they play hockey but they do, we are playing in Kenya, again where you don’t think they’d be playing hockey. Then the players take us around their communities and for instance in Kenya all the animals are dying because of climate change, it is really sad. And the communities in the countryside that rely on this eco-system are collapsing and everybody is going to the slums, and it completely turned the Country around. In Finland, which is a hockey-playing Country, 50% of the reindeer died in one year because of climate change. So Santa’s reindeer are dead because of climate change.

We are probably halfway there with this movie. The Pope is the honorary captain of our team.

Photos by Luca Ortolani.