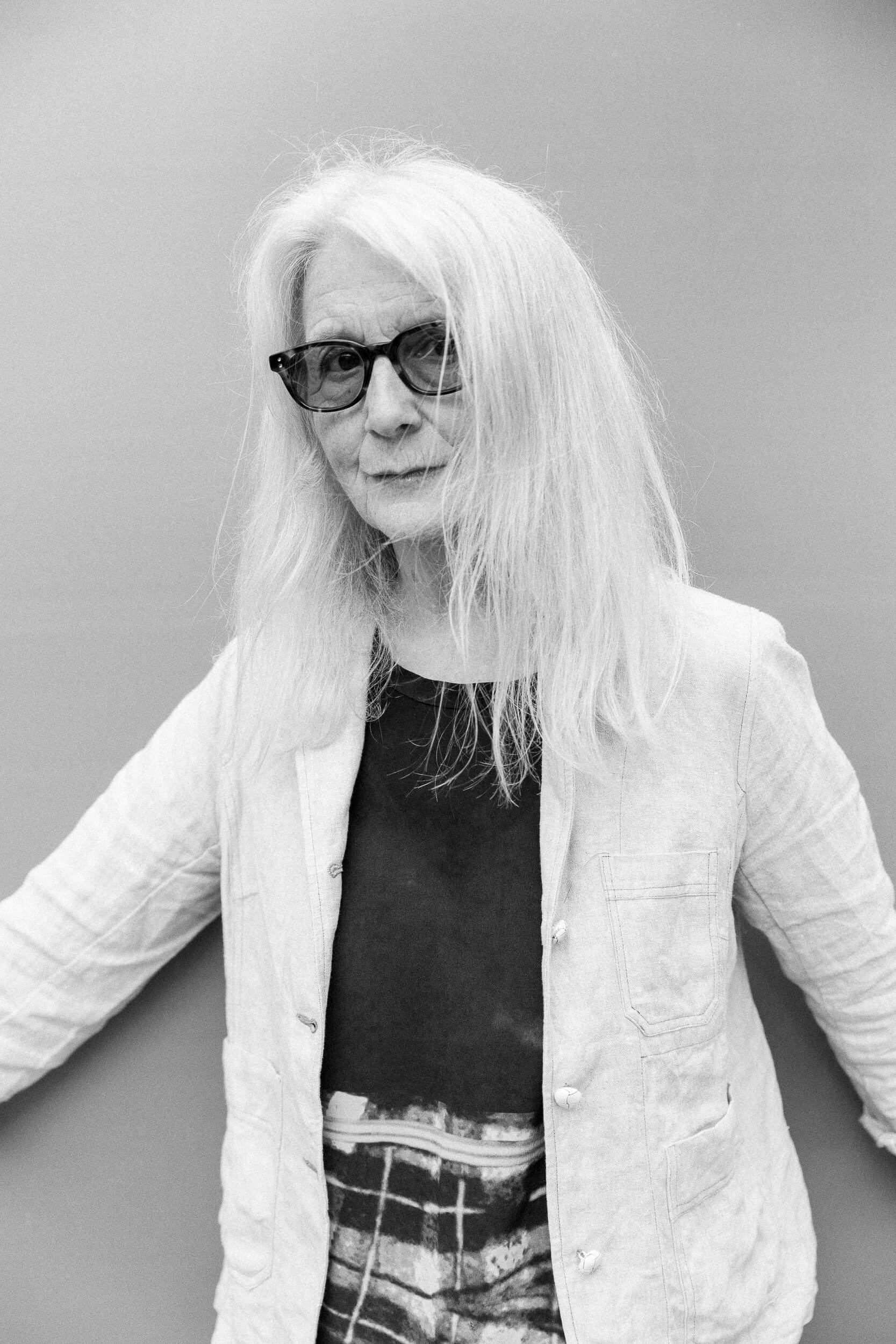

While sitting in front of Sally Potter, you immediately realize two things: that of being in front of a figure who has revolutionized the world of cinema, and the feeling that the exchange of questions and answers will not be a simple interview, but more a creative flow and, as she would say, fluid, between work, life and freedom.

30 years after the incredible success of “Orlando“, presented at the Venice International Film Festival, director Sally Potter returns to the Lido, but this time, she does so with a short film, “Look at me:” a story where feelings and music co-star the couple formed by Chris Rock and Javier Bardem. In 16 minutes, Sally Potter digs into the bowels of anger and misunderstanding to find, in that defined frame given by the shape of the short, a new meaning to the concept of “freedom”. A strong and poignant feeling that moves on notes that can range from those produced with a drum kit to the most nostalgic ones of tango, on which Sally has learned to dance over time to allow herself to evolve (as a director and person) and to go deep into the things she believes in, always doing what she loves the most: working.

First of all, congratulations on your short movie, I loved the interaction between Chris Rock and Javier Bardem in it. How did the idea behind this short movie develop? Because I read that it was supposed to be a part of your previous movie, “The Roads Not Taken,” where Javier plays a different kind of character.

Well, in the original writing, I told them it was interesting to have a story inside a story, where the character was so different, you know, like, if Leo would’ve made different choices in his life, taking another road; but, even while I was shooting it, I was thinking, “this feels like a different film” [laughs]. And then, when I got in the cutting room, I thought, “This is a different film”. So, I had to remove it from the film, and then I needed to wait a little bit to make it into a short film. It was like a story inside a story, so I took it out and made it into a film in its own right.

The feeling that I had while watching it, was that it almost felt like a part of a feature movie because I wanted to know what happened before and what’s going to happen in the future of these characters. What was it like to come back to the “short film” genre?

It’s exciting actually because I think that a short film is not just like a short version of a long film, and it’s not a kind of practice. Sometimes, people say that young filmmakers need to make a short, so they’ll learn that way, and then after they make a feature, actually it’s interesting to do the other way round because it’s a very particular discipline. You have to tell a story in a short period of time that has beginning, middle, and end, which has a development, which has a surprise, which has big themes but no, like, explanation, you know. It’s a wonderful discipline, it makes you cut away everything that’s not important, and just stick to what’s important.

“Sometimes, people say that young filmmakers need to make a short, so they’ll learn that way, and then after they make a feature, actually it’s interesting to do the other way round because it’s a very particular discipline.”

What I found interesting while watching the movie is how the concepts of freedom and imprisonment are blended. Like, Leo, plays his drums in a cube-like cage, and the drums are like the emblem of freedom because when he plays, he feels completely free. What does “freedom” means for you, both in art and in your life?

We were just talking about the short form, right? You could say that the short form is a cage because it has its constraints, but you find freedom inside that cage, just like you find freedom inside a script; a script doesn’t include everything in the whole world, you make choices and that’s the cage if you like, and then within it, you find freedom. It applies to every art: a painter works inside a frame, it’s not like a negative cage, it’s a frame.

I think, for me, as a filmmaker, freedom is to go deep with things that I care about and believe in, even if it’s not fashionable. Maybe, especially if it’s not fashionable. [laughs] It’s wonderful if you get the financial support to be able to explore those ideas, but sometimes I’ve made things without financial support; often, I write things before nobody even knows I’m working on it until it’s done. So, I think, freedom is not so much about support, it’s an attitude to permit yourself to go deeply into something you believe in.

Another fact that I noticed is the use of music: of course, Javier Bardem plays a drummer, but also I love when he goes on the rooftop and then makes music with the drums sticks and the trash bins. Since you are also into music and composing, what does music represent in this film? And how was it for you to work on its music?

I used music in this film as a contradiction to what’s happened. So, in a sad moment or when there’s the most explosion of anger, I use a very gentle calm music. At the end of the course, it’s tango, which is a kind of love music, which is also slightly ironic music, and nostalgic, for something you’ve lost. I try to write music that somehow conjures up something which you do not really see on the screen but which feels an interesting dynamic relationship with what you see on the screen. It gives extra energy somewhere to your brain to link with neurons, I don’t know how to describe it, because it’s metaphysical what music does to you. It’s magic.

I liked it at the end when they hug each other and there’s like this dance from the past playing, it was powerful I think. The movie is also about male humiliation and anger, with protagonists not being able to communicate their feelings to each other. So, there’s also this theme of miscommunication and how to be able to express your feelings. Do you think it’s hard for men, and for humankind in general, to communicate their feelings? What was the message regarding that?

Less so now maybe, but in general, men are brought up to try to control or suppress their feelings, and women are brought up more to express their feelings. I think a lot of very difficult things happen for men when they try to push their feelings down; it comes out somehow, but it comes out in the wrong way. So, like, anger for men, that’s usually a distortion for something else, maybe behind the anger, there’s sadness, or loneliness, or frustration of some other kinds. I think it’s complicated for men.

“Freedom is not so much about support, it’s an attitude to permit yourself to go deeply into something you believe in.”

When Leo is angry or overwhelmed, he looks around like he’s searching for something or someone…

He’s looking for a way out. And the only way out he knows is to end his life actually, so it’s a moment of despair and difficulty. And he somehow finds this solution, he can’t, you know, he’s trapped in his feelings. This kind of mental health crisis for men, it’s a very big issue.

They are opening a discussion right now about it, luckily, but it’s a long way to go.

It also struck me that the premiere of this short movie takes place in the same place where “Orlando” premiered 30 years ago. I was like, “Wow,” because I saw it, like, 10 years ago. How does it feel for you to come back here, in Venice, in the same scenario? And what do you feel has changed for you and in your approach to your work during these 30 years?

I love Venice Film Festival, it was indeed an incredibly important moment in my life when the premiere of “Orlando” was here. 30 years later… So, first of all, I can’t believe it, you know, like, “Really? Are you sure it’s not like 6 years ago?” [Laughs] That’s a kind of strange feeling, the passing of time, how have I changed? I don’t know. I hope I’ve developed a bit. I think I’m a better director for actors now than I was. I mean, I had an opportunity with Orlando to prepare a lot with Tilda, so I did a huge amount of work with her. But, now, I think I understand a lot of different kinds of actors more, that’s something which has changed. I don’t know how to answer that actually, I’m sorry. I feel the same and different. That’s why I can’t believe 30 years have passed because I think, “But I’m the same person who made that.” And, at the same time, I never knew who I was anyway.

I don’t know who I am, I just know that I get very engaged with what I’m making. So, I don’t think about myself and how I am, I think about the thing I’m working on, and the people I’m working with. My focus is outside, you know what I mean?

What’s your most remarkable act of rebellion?

Making “Orlando” was an act of rebellion; now it doesn’t seem like it, right? But at that time, everybody thought, “You can’t make a film of Virginia Woolf, you can’t make a film about someone who is a man and now’s a woman, nobody would ever believe this or agree with this concept,” so that was quite rebellious. And then, I think, I made a rebellion after “Orlando”, which was very commercially and critically successful, to then make a film in which I was performing. This was ridiculous, this was considered like career suicide. [laughs], you don’t do that. And I think often I’ve done that, I’ve made a film that people think is the opposite of what you’re supposed to do at that moment.

What’s your biggest fear?

My biggest fear is to stop working because I love working so much. At the moment, I’m writing a lot of music; so even when I’m not filming, I’m working all the time, whether in writing or composing.

Should we expect something more about it?

Music? Yes.

“My biggest fear is to stop working because I love working so much.”

What does it feel for you to feel comfortable in your skin?

I feel very comfortable in my own skin when I’m dancing when I’m moving around. When I’m working, I feel very comfortable in my skin. I’m most comfortable when I’m not thinking about my skin [laughs], my body, or anything else, I’m just in the state of being, engaged with stuff. So it’s a fluidity… I quite agree with the Buddhist concept that the self doesn’t exist. There’s a lot of emphases now on identity, me, me, me, me, I’m this, no I’m this… I don’t know who I am. And I much prefer that feeling of fluid into change with all the levels of reality.

What’s your happy place?

Working [laughs]. I love writing music. I love working with artists. I love making films.

Another curiosity, since we are talking about music. What music were you listening to while working on “Look at me”?

I had already written this music, so If I was listening to anything, it was this music. I didn’t listen to anything else. Silence is good. [laughs]

Photos by Luca Ortolani