There are stories that can be told with no different words than true words, those that are a perfect fit, even though they cut you through.

There are stories that need to be told so that they’re not repeated.

There are stories that cannot be sugarcoated.

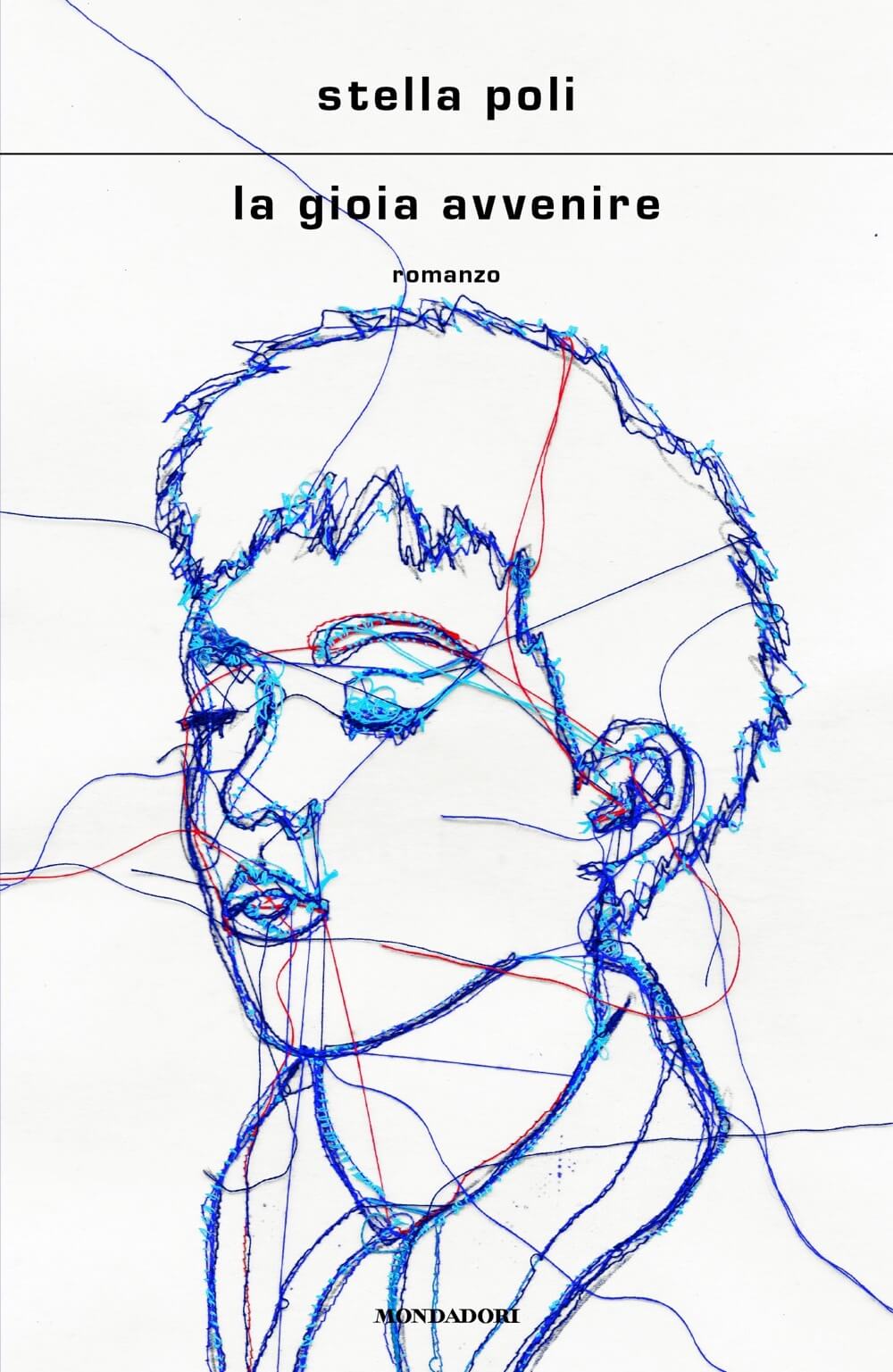

“La gioia avvenire” is the story of Nadia within the story of Sara: the first one, a victim, the second one, a witness. Both, for different reasons, are powerful stories, but at the same time full of impotence. 14-year-old Nadia was seduced by an older man and then, by that same man who’d made her feel so beautiful, adult, desired and desirable, she was abused. Sara was her therapist, the storage room of that traumatizing piece of life, the witness with her hands bound, the only one really trying to seek justice when, perhaps, it’s too late to find it.

From her debut novel, Stella Poli doesn’t cut anything out besides the superfluous words, to create those ellipsis that allow “to catch one’s breath, both for the reader and the writer”. To tell a story that sadly sounds familiar to everyone, and that Stella’s writing untangles with a perfect balance of brutality and gentleness.

Dropping it off with a heart full of hope, as a reminder so that such stories stop happening.

Such a raw, plausible story is never easy to tell, and the hardest part is probably starting to write it. How and where did you find the words?

The first words are almost an attempt to take back the desire to tell the story: in the incipit, there are things that should never be said. It’s a sort of last-minute retraction, a voice we hear but can’t tell to whom it belongs because it’s very hard, as you were saying, to find a way to start, to find motivation, as well as to think that you can actually say something like that out loud.

Going back to how you defined the story, that is “plausible”, what comes to my mind is all the times that people have come to me at the end of my book launch events, people whom I didn’t know, telling me that there were pieces of the story I’ve written to which they could partially relate because, even though it’s characterized by a series of unique details, it’s a sadly universal or almost universal experience.

The beginning corresponds with the first words of Nadia’s narration, and that was the very first part I wrote. For a long time, I’ve thought it wouldn’t have had a sequel or a purpose that could be different from a simple pouring on the page; however, later on, all these narratives about the unjust and failing justice, that at times can be very exhausting, came out. After that, the psychotherapy part of the plot, and the whole novel built up on this crux.

The protagonist of the story, Nadia, is a victim of an abusive relationship that she neither wanted nor could avoid when she had the chance. Do you think she couldn’t say no because she believed she deserved it? Due to inexperience? For revenge? Why do you think we accept even what we sense will harm us?

In my opinion, we have this idea, which perhaps helps us have enough hope in this world, that there is a precise moment when you say yes or no, a well-defined moment of consent. However, in reality, it is very difficult to pinpoint the moment when there is still a possibility to express explicit consent or stop the situation. Nadia simply finds herself trapped in things that go over her head, and in addition to the abusive relationship, she is a very young girl who doesn’t have the tools to truly decipher what is happening, in my opinion. And what little she does understand, she processes with the few and imperfect tools that a 14-year-old girl should have. In this strange game with a person in whom she had pre-existing trust, she never controls it, at least not explicitly. Nadia is unable to express her consent; the situation overwhelms her.

But sometimes, in general, it is also very difficult for us to even realize what we truly desire in that moment.

Earlier, you mentioned the issue of justice, which is clearly a key theme in the story. How just is justice really?

That’s a great and very relevant question.

The point is that human justice is a system that must operate within a set of universal parameters that often have a distance from individual experience, and that is one of its flaws. Moreover, because it is human, legislation is constantly changing and being updated, sometimes in an extremely imperfect manner, as we know from various historical cases and even current ones. So, we have this somewhat platonic idea of justice, at least initially, the idea that it is almost a restoration of balance when there has been a violation. However, that is not what happens in jurisprudence. There are, anyhow, many other theories of justice that do not emerge as much, such as the idea that there can be not only a trial in court but a transformative process as well.

Fear and a sense of abandonment are two other important concepts in the story. Where did your need to tell these stories come from?

The first part is Nadia’s own story, which is a true story that I came across and which is very difficult to handle once you become aware of it. I’ve recently read a beautiful quote by Carrère, citing a lawyer in a trial, stating that the testimony of witnesses is also a for of “support” or a deposition in its etymological meaning. So, I wanted to unload part of this weight.

Nadia refuses to acknowledge what happened to her for a long time. Why do we often deny reality in order to avoid facing the pain?

Because focusing on responsibility in the facts, even just admitting to oneself that it happened, or even just finding the right words for something, means having to deal with that same piece of reality, which is not exactly the same. When one recognizes the violence, they will then have to face all the consequences of admitting responsibility, and that is not easy or immediate either. Repression, on the other hand, is one of the most natural and common mechanisms when a trauma occurs.

Memory sometimes plays tricks on us, leaving gaps instead of processing. But is it true that “suffering is useless,” as Pavese says, as you mention in the book?

To some extent, yes. I am annoyed by what has almost become a sort of commonplace idea, the Kintsugi, the idea that the crack can become something precious and tremendously enriching. Most of the time, it’s simply a laceration that one may try to suture in various ways, even imperfectly, but I don’t believe that all of this serves any purpose. Especially in this story, I don’t believe in pain as a process that improves people and makes them stronger. At a certain point in the book, it is said that one does not want to cling to this pain, not wanting to carry it as a “badge of distinction.” This is something one discovers early in life because there is not a person who does not have a series of infractions, traumas, there is so much pain, so it is not distinctive at all. Sometimes, it seems more like a narration, simply something that happens and is processed in the best possible way.

The title of your novel refers to a way of looking at the future, or rather, looking at the past in view of future happiness. The characters in the story don’t seem capable of doing that, perhaps because their past is too full of traumas? What do you see in your future?

The title is the same as a poem by Franco Fortini, written in ’46, after the collective historical trauma, the Resistance, the civil war, and he says that the idea of being able to forget seems presumptuous, going back to what we were saying earlier. He says instead that we will go through it and celebrate what has happened to us.

It’s true, this “a venire” (“to come”) which becomes a single word, “avvenire,” meaning “future,” but perhaps the gaze is not entirely backward. I believe there is a strong desire for future in different characters, who sometimes seek it in a disjointed way, but this also happens and is understandable and inevitable. This is a book that has a great desire for what comes next and tries to search for it. In my future, I hope there will be a lot of joy, but I don’t know, it’s a complicated question.

Speaking of your writing style: syntax and punctuation, a pose reminiscent of poetry, are sharp and raw, like the events narrated, the topics addressed. Is this a specific choice or is this the writing style that you feel most comfortable with?

I have always written only very short stories, and usually, I tend to write a first draft and then cut them down gradually. So, it’s something that comes very naturally to me, this idea of pruning and creating something that’s almost unfinished, some suspended phrases. It’s just my way of writing, which in this case, I thought could help the story, a certain number of ellipses and empty spaces to interrupt the gaze. I feared that an unfragmented or very dense story would become too difficult to sustain, instead, in theory, this structure has several escape points because ellipsis helps to catch one’s breath, both for the reader and the writer.

Indeed, I appreciated it a lot; it was almost like reading into the minds of these people, whose thought mechanisms I suppose were quite fragmented by pain.

Yes, because then, as you mentioned, even memories of traumas are often genuinely fragmented, so the idea of a splinter almost emerges, and everything becomes very difficult to consolidate.

“I tell stories because I don’t want to get attached to my pain.” Does it also apply to you? Is this what drives you to write novels, stories, and poems?

No, it’s not that, but yes, I find that there is almost this temptation at times to nestle even in discomfort: when they are prolonged pains, one almost risks getting closed inside them. However, I think that writing helps find a way to help run around it and escape, not thinking that pain characterizes us. At a certain point, Sara says that writing a story also helps show everything around us; this comes out during the part of the story where they search for photos of a past time, and thus, the surrounding life emerges, which almost wasn’t being looked at precisely because one always looks at the stake.

Consent is often talked about, especially in the last few decades, especially in the sexual sphere. But what is it that we lack to truly understand its meaning and recognize its value? We see in the novel how it is difficult to truly comprehend it from both a legal and human perspective.

Consent is a very elusive notion, not just in practice. I’ve read a series of essays attempting to give theoretical definitions of consent, struggling, despite it being a concept to which we give enormous procedural weight. There is a very clever French scholar, Manon Garcia, who says that perhaps we place excessive weight on this notion that is so difficult to define, and in fact, it’s something on which I think it would be useful to debate much longer and perhaps with fewer ideas and preconceptions. The debate in the media is still very cruel and distorted regarding this topic, so I find it positive that it is discussed in various ways since it also helps us better focus on ourselves.

At one point, in this essay called “What Do We Talk About When We Talk About Consent” it is said that it is important to protect oneself but that it is also beautiful not to lose the possibility of not knowing, not losing the uncertainty for a certain stretch, which is a significant part of desire, of fully experienced sexuality, the “not knowing”, the possibility of changing one’s mind.

So, consent is really a concept that seems very clear and defined and even, in a way, simple in its explanation, as if there were really a moment when one asks “yes or no,” but instead, it is much more nuanced, and it needs to be nuanced.

What is the next story you dream of telling?

I don’t know yet, in the sense that I have two or three that are still very indefinite, and I’m taking the time to let them define themselves before starting to work on them. I don’t think I will abandon the genre of short stories, but I would also like to try the structure of a novel again. We’ll see.

Which book are you currently reading, and which one would you recommend?

One of the books I have just finished reading is “V13” by Carrère, which I really enjoyed. Now I am reading an essay, “The Editorial Work of Natalia Ginzburg”, whom I greatly admire, and it was an aspect of her life that hadn’t been valued yet. Then, I really like Anne Carson, so I would recommend reading many of her works. “Autobiography of Red” is very beautiful, in my opinion, but also “The Albertine Workout”. Among the not-so-recent classics, I recommend “Family Lexicon” by Natalia Ginzburg to anyone who hasn’t read it, as well as “A Private Matter” by Fenoglio, which I think is a perfect novel. My favorite books are “Moby Dick” and “Crime and Punishment”; I can never know which one wins, I would say they are on equal footing [laughs].

Thanks to Mondadori.