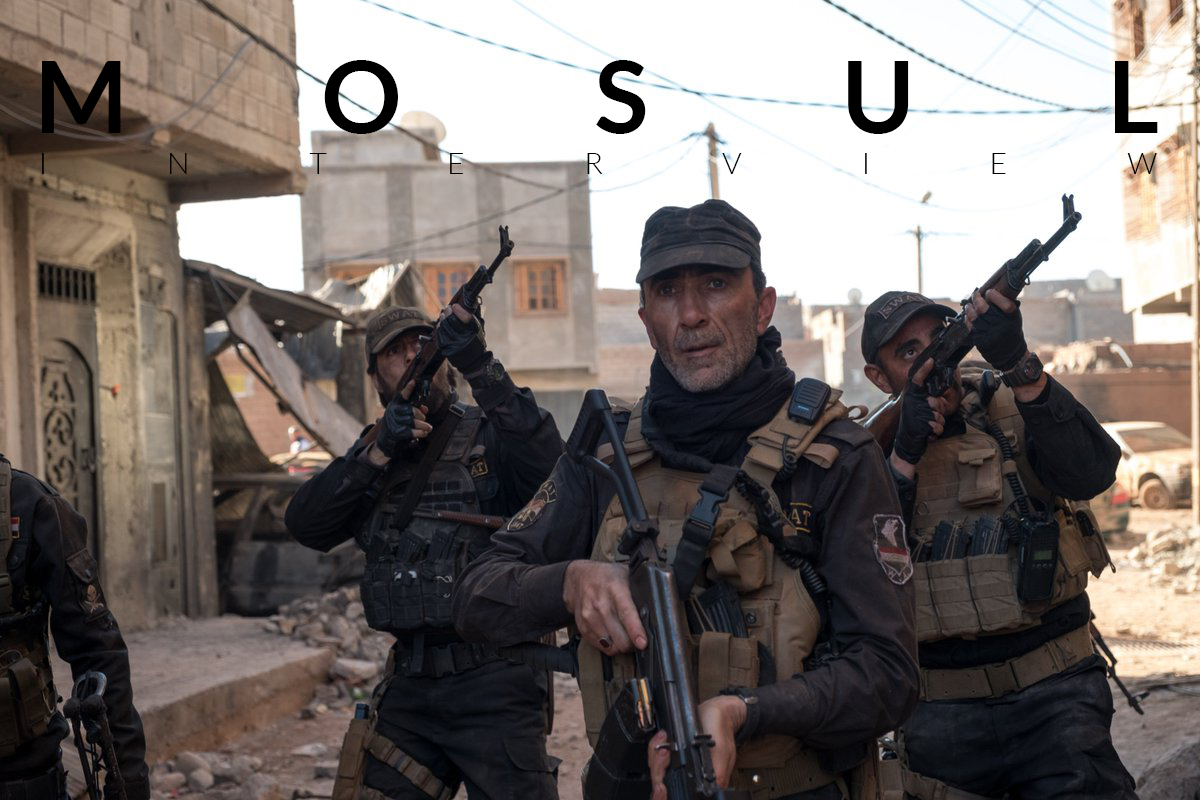

Are you able to hold your breath for 100 minutes? We hope so because that’s what you’ll have to do when you watch “Mosul” by first-time director Matthew Michael Carnahan (screenwriter of “Deepwater Horizon” among many) and produced by the Russos brothers and executive produced by Mohamed Al Daradji.

100 minutes to show the audience a day in the life of the Iraqi SWAT Team in Mosul. 100 minutes to show the courage of these men that would do anything to get back their city and families. 100 minutes to develop these characters and showing the most touching and simple human gestures.

We had the chance to talk with the director (D) and executive producer (P) on how starting from Luke Mogelson’s article they brought this project to life and what were the main challenges and the importance of telling these stories.

A question for both of you: what is for you the importance of telling this story?

____________

D: It rose out of Luke Mogelson’s article; it was sent to me, as a writer, and within the first page I was completely enthralled.

In the first pages, there’s the piece about the criteria to be a member of the SWAT team, of course, you have to know what you’re doing on a battlefield with weapons, but you also have to have lost someone to ISIS or been wounded by ISIS. I just thought it was such a brutal ticket to entry that from that point on I was hooked, and the thing I walked away with from the article, that made me pick the phone up to the Russos immediately after finishing it and say, “alright, if I can direct it.”

It’s that notion that I didn’t know that these men existed, I didn’t know these people existed, I had a very skewed vision of what Iraq was, Iraq and the United States is synonymous with war, the word itself. While I was a child, the first Gulf War happened, and someway it basically continued even until now. And it wasn’t until I read Luke’s article that I realized just how skewed and little I knew and not only that, but these people are so much more like me, and I like them, than anything that separates us: language differences be damned, they want the same things for their families, their homes, their cities that I want for mine, and further I just pray that I would have a similar level of courage that they have to display on a daily basis in order to have a hope of winning those things back.

It was that notion about all decent human beings wanting the same thing regardless of language, culture, gods, continent you’re born on, that’s what I rather do, embrace and show on screen: and it’s part of why I wanted to tell it in some version of the Arabic language, I had this gut instinct while I was reading it, because to me that difference could underscore the similarities, intuitively you see these people speaking a very different language than we speak in the United States and yet they’re all sacrificing themselves to get back to this thing that you realize, at the end, is their homes and their families and that to me is a universal human message. So, that’s how I came to it, that’s why I wanted to do it some of the ways I chose to do it.

P: When I read the script that Matthew wrote, I already knew about the SWAT team and when I was contacted by the company I thought, “ok, I had refused a lot of American projects about Iraq, because sometimes I don’t see my point of view, the Iraqi point of view,” but when I finished reading the script, I said, “wow.”

And then I was on the phone with Matthew, we spoke for one or two hours, it was incredible, it was 1.39 a.m. in Baghdad, the connection kept cutting off and I was so tired [laughs] and I had the release of my new film in Iraq, which was going to be the first Iraqi film to be released, so I was so tired but at the same time I was so passionate about the script. And when he told me it was going to be in Arabic, there were going to be Iraqi actors, I said, “wow, ok, this is the project, this are the boys that need to be told” and also Mosul, and also Daesh, because it’s going to be the first fiction film to be made about the liberation of Mosul, and it’s very close, I received the script around January, February 2018 and Mosul was still at war; On December 10th. the Prime Minister of Iraq had announced the liberation of Mosul but not of the whole city, and I had been in Mosul 3 months before, right next to the war zone, so when I read the script I was like, “wow, this is the project we need to make now,” for a lot of reasons: as an Iraqi man, as a filmmaker, you feel the side we’re on, in Iraq they bullshit us, they say to us “we are fighting in behalf of the world.”

You have your friends and your family being killed because of the war, but you don’t see the enemy, it’s not a classic war, so the script made me say, “now I can see that we’re maybe fighting in behalf of the world,” in the way Michael wrote it and represented it, showing the positive side of it – there’s a lot of positivity in the middle of chaos, so that was one of the reasons that made me want to engage in the project.

“They want the same things for their families, their homes, their cities that I want for mine, and further I just pray that I would have a similar level of courage that they have to display on a daily basis in order to have a hope of winning those things back.”

“I had refused a lot of American projects about Iraq, because sometimes I don’t see my point of view, the Iraqi point of view…”

What were the main challenges of bringing this project to life?

____________

D: The limitations of a first-time director. [laugh] But what people would have thought would be the biggest challenge – the language and the cast – turned out to be the greatest strength, the very best thing that we did. So what you would think is the first candidate in terms of an answer, is the exact opposite. It was nothing production-wise, because it was as seamless as it could be and I was as supported as any first time director or any director has ever been, so I think for me it was just doing justice to history and the biggest challenge was:

“How do I encapsulate the three years of hell that these people have had to go through? Hour by hour combat, losing friends hour by hour and they never retreated, when everybody else was fleeing, they stayed and fought; how do I encapsulate that across the span of one day, a day in the life of the SWAT team, and still have enough time within that to develop characters, to show who these people are, to show who the Major (Suhail Dabbach) is, to show how Kawa (Adam Bessa) goes from this recruit to, at the end of the movie, maybe the leader of what’s left of the team?”

That to me was the biggest challenge, on a scene by scene basis that’s was foremost on my mind, that’s what I was thinking about: “Am I doing enough in both of those regards, in this particular scene, to serve this thing that I hope is the goal of my movie?”

That was the biggest challenge, but one that I think never let me look away from the things that I should be focused on in that movie, if that makes any sense. And I think Joe, Anthony and Mohamed realized that I had my hands full of that, so all the nuts and bolts worries, like I never worried about the cost of any particular thing, I was more like, “that’s what we need, that’s what we’re able to do.” There was no crazy language barrier, no crazy production barrier, because there’s actually a vibrant production community in Marrakesh especially, so the biggest challenge was, “can I tell the story the way I need to tell it?” It’s probably a ridiculous, obvious answer, but it truly is the answer.

How did you manage to perfectly recreate Mosul in Marrakesh?

____________

D: It was Phil Ivey, the production designer, and his team. He’s done all of Neill Blomkamp’s movies, he did “District 9,” he did “Elysium,” he’s spectacular and he’s also, like everybody on this movie, one of the nicest human beings I’ve ever met, he’s this guy from New Zealand who’s so unassuming and it’s rare that you meet someone who’s that lovely on a human level and also really good at what they do.

Phil, working with Luke Mogelson’s fixer in Mosul, who got Luke in with the SWAT team, he working with Mohammed, working with people that we had on the production who knew this part of the world, who knew war, built binders of reference material and he just literally recreated these blown-out pieces of a war zone in an otherwise lovely city like Marrakesh. He recreated this northern Iraqi devastation and that all credit to him and his team. Phil did an amazing job and there were things like the minefield that they have to drive through to get back to the shitty side of the city, in the original script that was the Tigris, that was the river, but there aren’t rivers in Morocco; we saw what they call the river and we said, “guys, this isn’t gonna work, this is a creek!” So, Phil was like, “what if we did a minefield and that’s the barrier?” Those on the fly improvisations that are just seamless and work in the movie because of him.

Basically, during the whole movie you hear gunshots, but then you have these touching scenes of humanity, like when Jasem brings the ice to Kawa’s cheek and holds his hand there, or the one where you understand, they’re going to see their families: how did these details come to life? How important were they to you when you were writing the script and how did you take care of them when you were directing?

____________

D: They were everything.

All those interstitial moments were where the movie was going to live or die because combat’s combat and there’s only so many ways you can do that and that people haven’t already seen. And I tried to do that in an as truthful and believable way as I could, based on the people I’ve talked to, I’ve never been in a battle myself, but I tried to do that as best as I could, but where the movie is going to live and die is with those characters and those quiet moments in between these moments of horror, where you see who they are. This idea I had, while I was writing it, that Jasem should pick up trash…

And keeps saying, “we have to rebuild, we have to rebuild…”

Exactly, to me was the most heartbreaking, beautiful way to show how this man wants to put his city back together again; when he talks about when he was a detective and how much he loved it, because he was good at it and he liked who he was then, the way he did it moves me every time, because he’s so goddamn great with that face of his, those eyes.

So, to answer your question, that to me was the upmost importance in the writing and in the directing, because, back to my early answer, that’s how I could develop characters in the span of this day that’s otherwise filled with horror, so how could I do it in the most compellingly and in the most economic way?

P: One of the most important scenes to me is the one with the Iranian general: “the moment of Kawa,” this is one of the biggest scenes in the film, I think, because it’s the moment where we see the main character, Kawa, and how it all forever changes for him.

Because Kawa feels like one of my students: when we were in Baghdad and Mosul was taken over by Isis, I had 20 students, and I was having this Film workshop there in Baghdad but I had to stop it and 7 or 8 of them joined the army and go. Two years later, one of them, Ahmad, who was supposed to be a very good cameraman, joined the army and Ahmad was the face of Kawa after he hit the guy. So, this kind of scene to me is a very touching scene, it was touching to see the character in the war zone, to see where he comes and where he goes.

D: I wrote that scene in particular not to show who Kawa is becoming, but also to put the audience in this position: if he hadn’t done what he did, if he hadn’t hit that man, killed his old partner, that whole room could have blown up. So, that level of brutality is forced on people: to do that is the right decision, the right thing to do? That’s the world that I was trying to show – there’s a version of the world where hitting somebody you know in the head, killing them, is the right thing to do, saves other lives potentially, that world only can take it all, that world can only change who people are.

And at the end, when he stands back up, puts his mask on and asks Amir how far his boy is from there, there are a couple of ways to see that and I won’t lay them out, but there are a few ways to look at Kawa at that moment.

That’s the world that I was trying to show, there’s a version of the world where hitting somebody you know in the head, killing them, is the right thing to do, saves other lives potentially, that world only can take it all, that world can only change who people are.

I hope this film can create more awareness, in the sense that every day we get all fiknd of new, fake news, one-sided news, while the film someway uncovered another reality which will get to more people. Are there other stories you’re planning to bring on the big screen to get us to know other realities?

____________

D: Not right now, only because I haven’t found anything half as compelling as this. I don’t know if I’m ever going to work on a set or be with a group of people that is just to die for as these people are.

In a larger sense, I gravitate toward the gaps in my own knowledge; in true stories, where everybody thinks they know the majority of the story and yet there are these details that most people don’t know, that’s why I wanted to get in the movies in the first place; “Deepwater Horizon,” for instance, the reason why I wanted to get involved in that was because it was the story of these 11 guys involved in this horrific fight to keep more people alive that I didn’t know of. I think it was lost in the scale of a massive ecological disaster as it was, which deserves its own coverage, but there were also 11 human beings, I met their families: there was one man who was studying to be an engineer, and I met his wife and his son who was born two days after he died.

Those stories, to expose a fuller picture of things, is why I want to be in the movies, why I want to wake up in the morning. So, I haven’t found anything yet that’s half as good as this.

P: I’m developing a new project by myself: it’s based in Baghdad and it’s about a woman in her late forties, driving her double-decker bus in the streets of Baghdad in 2006, when the city was chaotically divided between the American army and al-Qaeda, and she has one aim: to collect homeless children, to try to teach them in her mobile school, which is what her bus becomes, and not because she loves children, she hates them, and then we’ll understand why she hates them, what’s the meaning behind her aim to educate those children, what she wants to achieve from that.

D: It sounds fantastic! It’s the first time I’m hearing this.

P: Yeah, I’ve just written the first draft.

Photos by Johnny Carrano.